This post is part of a series of posts and resources on drones and the world of intelligence. For a complete guide to drone hunting, click here. For resources on how to find and spot drones, click here. For our Multimedia Portal on drones and intelligence, click here.

A version of this story will appear in The Draft.

By Dan Gettinger

On the fourth Saturday of every month, a group of Quakers meets outside the gates of Royal Air Force Croughton, a communications base in England that is run by the U.S. Air Force. For the past 10 years, the monthly meetings have been a forum for discussing the use of force. “People come to our Meetings for Worship with a concern for peace,” said Maria Huff, who organizes the meetings, in an email to the Center for the Study of the Drone. “[M]ilitary actions should not be regarded as commonplace and routine.” Lately, on the grass in front of the gates, the discussion has turned to drones. In early October, U.K.-based Drone Campaign Network organized a demonstration in front of RAF Croughton intended to draw attention to Britain’s drone operations and American communications facilities on British soil. The U.S. relies on a number of bases overseas to facilitate drone operations and the distribution of intelligence.

The United States may be withdrawing from Afghanistan, but elsewhere in the world, American military commitments are on the rise. Drones are a growing player in these operations; not just in the campaign of targeted killings in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia, but also in the air war against the Islamic State. Beyond offensive action, drones are an essential piece of the military’s ability to collect intelligence from the air. While bombing campaigns will inevitably come to an end, the demand for information by commanders and civilian decision makers is unlikely to decline, nor be limited to geographical areas of active hostilities. As General “Hawk” Carlisle, the commander of Air Combat Command, put it to reporters last November, “I’ve been in the Air Force 36 and a half years. The demand [for intelligence] has never gone down, ever. It just continues to grow.” In an increasingly volatile international security environment, military planners face an essential challenge: how to ensure that intelligence assets—drones, manned aircraft, satellites, and other platforms—can attempt to meet the demands of decision makers.

The Pentagon is taking steps to upgrade its capacity to deliver intelligence. It plans on spending $2.9 billion on more unmanned aircraft for each of the service branches. The Air Force has also created a new numbered force, the 25th Air Force, to manage the collection and dissemination of intelligence; with more than 27,500 members at 71 locations worldwide, the 25th is one of the Air Force’s largest commands. The military is investing in a global architecture of bases that support intelligence operations. These installations serve a variety of purposes. There are bases in at least 10 different countries where the drones are located and maintained. Other bases serve to provide the essential communications link that allows the operators to fly the unmanned aircraft from within the continental United States. At intelligence hubs like Virginia’s Langley Field, raw video data from the drones is deciphered and turned into actionable information for the decision makers. Together, these bases make up the intelligence system without which the drone, by itself, would be useless.

The ability to strike anywhere in the world from the comfort of a trailer in Nevada is made possible by complex communications and logistics infrastructure. Each of the bases that houses drones requires a large number of personnel to maintain the aircraft, provide security, and launch and land the drones. The larger, more expensive aircraft like Predators, Reapers, and Global Hawks fall under what the U.S. Air Force calls Remote Split Operations, meaning that personnel can control the aircraft both from a ground station that is forward deployed as well as from an airbase within the continental United States. The Predator and Reaper drones rely on both fiber-optic cables and satellites to receive instructions from the operators in the United States. Signals from the Ground Control Station in the United States travel via an undersea fiber-optic cable to Ramstein Air Base in Germany or Naval Air Station Sigonella, Italy. From Europe, the signals are beamed up to a Ku-band satellite, and from the satellite down to receiver inside the drone.

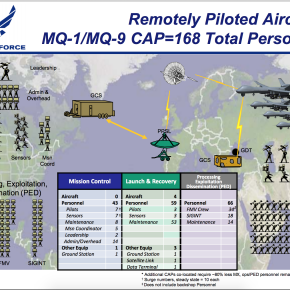

Beyond the pilot and sensor operator, dozens of people—including military lawyers, imagery analysts, intelligence advisors, mission controllers, and senior commanders—participate in the operations from around the world, communicating in real-time over radio and chat rooms. The drones are divided into Combat Air Patrols, each consists of four aircraft and are designed to provide 24-hour capability for every day of the year. For the MQ-1 Predator or MQ-9 Reaper, some 168 personnel are required to maintain each CAP.

Beyond the pilot and sensor operator, dozens of people—including military lawyers, imagery analysts, intelligence advisors, mission controllers, and senior commanders—participate in the operations from around the world, communicating in real-time over radio and chat rooms. The drones are divided into Combat Air Patrols, each consists of four aircraft and are designed to provide 24-hour capability for every day of the year. For the MQ-1 Predator or MQ-9 Reaper, some 168 personnel are required to maintain each CAP.

The military has made periodic investments to these facilities that link the operators in the United States to the unmanned aircraft. In the FY 2011 budget proposal, the Air Force allocated $10.5 million to build a new Satellite Antenna Relay facility. This investment was necessary, the Air Force argued, in order to “satisfy the long-term SATCOM Relay requirements for Predator, Reaper and Global Hawk, eliminating current temporary set-ups.” In the FY 2012 budget proposal, the Air Force allocated $15 million for a similar project at Sigonella Air Base. This Satellite Antenna Relay facility was needed as a backup to Ramstein. It could carry half of all communications between the continental United States and the drones flying in the theaters of operations.

Satellite imagery from 2012-2014 showing the construction of a drone apron at Chabelley Air Field in Djibouti.

Outside of Afghanistan, the largest drone base is believed to be Chabelley Air Field and neighboring Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti. In 2012, a report by the Washington Post identified identified Camp Lemonnier, a former French Foreign Legion outpost, as the “centerpiece of an expanding constellation of half dozen U.S. drone and surveillance bases in Africa.” In 2012, the Navy intended to spend nearly $62 million on improvements to Camp Lemonnier, extending and adding taxiways and building support facilities for aircraft. From Camp Lemonnier, drones and special operations forces were launched on mission in the Horn of Africa and Yemen. In 2013, at the behest of the Djiboutian government, the U.S. moved the Predator and Reaper aircraft to Chabelley, a neighboring and underused airfield. That year, the Washington Post reported that another U.S.-operated base, this one in Saudi Arabia, played a key role in U.S. drone strikes in neighboring Yemen.

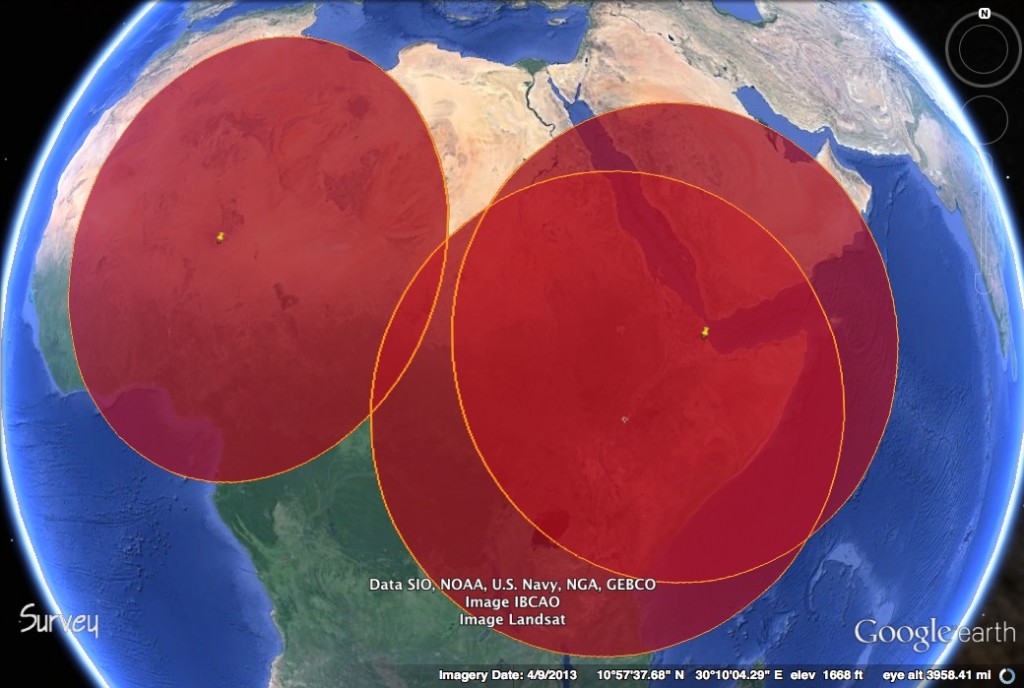

Drones are stationed at a number of U.S. or partner-operated airfields around the world depending on where the aircraft are needed. Drones have been located at a base in the Seychelles (Reapers), Naval Air Station Sigonella in Italy (Global Hawks), Agadez and Niamey in Niger (Predators), N’Djamena in Chad, Arba Minch in Ethiopia (Reapers), Al-Dhafra in the United Arab Emirates (Global Hawks), Naval Air Station Anderson in Guam (Global Hawks), Misawa Air Base in Japan (Global Hawks), and Incirlik Air Base in Turkey (Predators). Within the continental United States, there are dozens of military bases where drones fly.

Drones are stationed at a number of U.S. or partner-operated airfields around the world depending on where the aircraft are needed. Drones have been located at a base in the Seychelles (Reapers), Naval Air Station Sigonella in Italy (Global Hawks), Agadez and Niamey in Niger (Predators), N’Djamena in Chad, Arba Minch in Ethiopia (Reapers), Al-Dhafra in the United Arab Emirates (Global Hawks), Naval Air Station Anderson in Guam (Global Hawks), Misawa Air Base in Japan (Global Hawks), and Incirlik Air Base in Turkey (Predators). Within the continental United States, there are dozens of military bases where drones fly.

The forward operating stations overseas provide surveillance and strike capabilities for a diverse set of strategic imperatives ranging from the 2013 French military intervention in Mali to the ongoing air campaign against the Islamic State. Based on the Pentagon’s construction budgets, some of these stations appear to be temporary locations for drones while financial investments in others indicate a more long-term presence. In FY 2014, the Navy allocated $61.7 million for the construction of reinforced concrete hangers for four MQ-4C Tritons, a variant of the RQ-4 Global Hawk, at Andersen Air Force Base in Guam. In FY 2016, the Pentagon has proposed spending $50 million for building a taxiway and apron to accommodate the MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper in Agadez, Niger. These projects reveal a few of the military’s strategic priorities. In a presentation at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in November 2014, Major General John Shanahan, the commander of 25th Air Force, suggested that in the future, ISR assets like drones could have fixed hubs around the world. Instead of allocating assets to individual commands, an arbiter within the Pentagon would parcel out assets according to need in order to achieve a “dynamic presence.”

Some overseas U.S. military installations are believed to provide targeting intelligence for drone strikes. In 2013, Human Rights Watch submitted a letter of inquiry to the United Nations asking for an investigation into whether the Joint Defense Facility at Pine Gap, a secret American communications base in Australia, was providing targeting intelligence for U.S. drones. Intelligence analysts at Pine Gap are believed to geolocate targets for drone strikes using information gathered by intercepting the communications of those potential targets. In April 2014, former Australian prime minister Malcolm Fraser called for the base to be closed, telling ABC News that “Initially Pine Gap was [used for] collecting information … it’s now targeting weapons systems, it’s also very much involved in the targeting of drones.” The Royal Air Force base Menwith Hill in England, another secret signals intelligence facility, is also thought to play a similar role in locating targets for drones.

Pine Gap and Menwith Hill were built during the Cold War and are staffed by agents from the NSA, the CIA, the National Reconnaissance Office, and the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency. Outside of an investigation into the Snowden documents by The Intercept, little evidence exists to confirm the role that these bases play in U.S. drone strikes. However, other U.S. bases play a more direct role in find targets for U.S. drones and manned strike platforms. In November 2014, the New York Times reported that al-Udeid Air Base in Qatar and Shaw AFB in South Carolina were integral to providing targets for U.S. airstrikes against ISIS/ISL. Whereas Pine Gap and Menwith Hill are believed to collect signals intelligence for U.S. drone strikes, analysts at al-Udeid Air Base and Shaw AFB scan imagery intelligence from satellites, U-2 spy planes, and drones for potential targets.

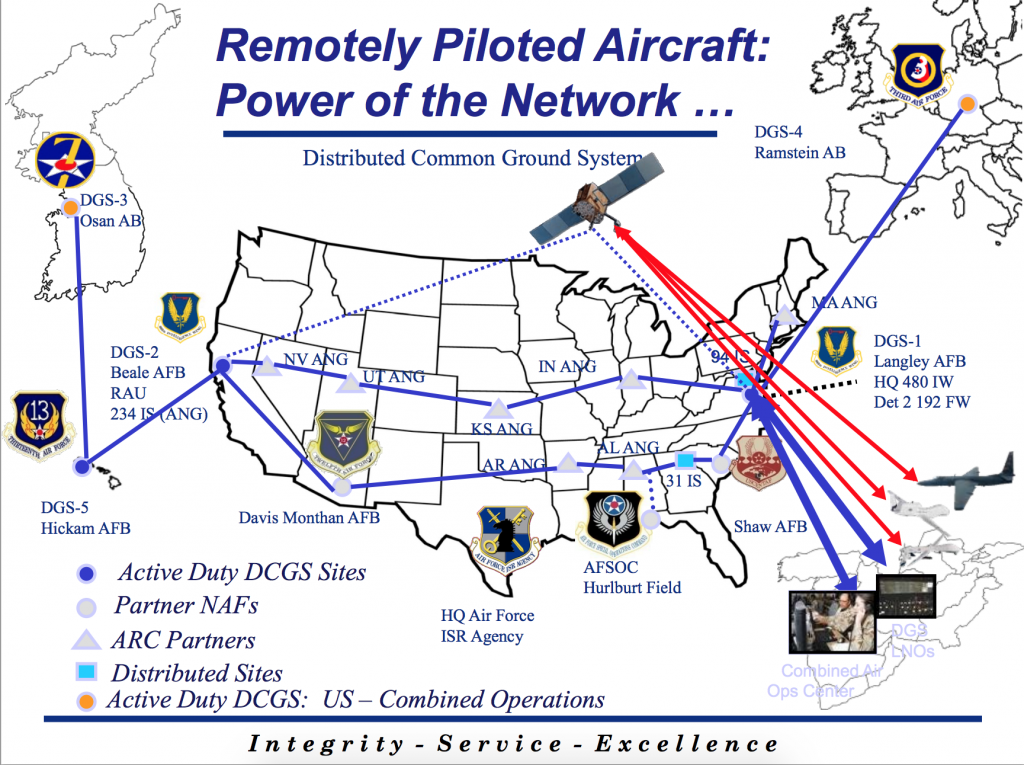

The third, and perhaps most crucial part of the network, is the bases where intelligence is analyzed and distributed around the globe. For imagery intelligence from drones to hold any value, it has to be analyzed and forwarded to the appropriate decision makers. Drone imagery is disseminated using the Air Force’s Distributed Common Ground System (DCGS), a network of 27 locations both within the continental United States and overseas, in Germany and South Korea. The DCGS allows the drone operators to be in live contact with teams of imagery analysts at a site corresponding to aircraft and to the geographical area in which the aircraft is flying. The size of each team is dictated by the platform; for example, an RQ-4 Global Hawk may have up to 37 analysts while the MQ-9 Predator is typically assigned seven. During a mission, the operators and analysts communicate in real-time over classified chat rooms, with the analysts identifying items of interest that warrant a closer look by the operators of the aircraft.

Langley Air Force Base in Virginia is the home of the DCGS and the headquarters for the 480th Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance Wing, a part of the 25th Air Force. The 6,000 airmen of the 480th ISR Wing process much of the raw intelligence coming from the Middle East. (They receive around 7 terabytes of data each day.) The 480th is divided into intelligence groups according to specific geographical commands and ISR platforms. For example, the 692nd ISR Group is headquartered at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii and is the primary station for exploiting imagery collected by the RQ-4 Global Hawk, MQ-1 Predator, and the U-2. In FY 2008, the Air Force allocated $16.5 million to expanding the DCGS facilities at Hickam. The DCGS embodies what the military calls “network-centric war,” which is the collection and dissemination of intelligence from numerous sources to the warfighter in real-time using high-speed networks. The system underscores how the global collaboration between drone crews, intelligence analysts, and combatant commanders to collect, analyze, and disseminate mass amounts of data is a formidable achievement of the post-9/11 era.

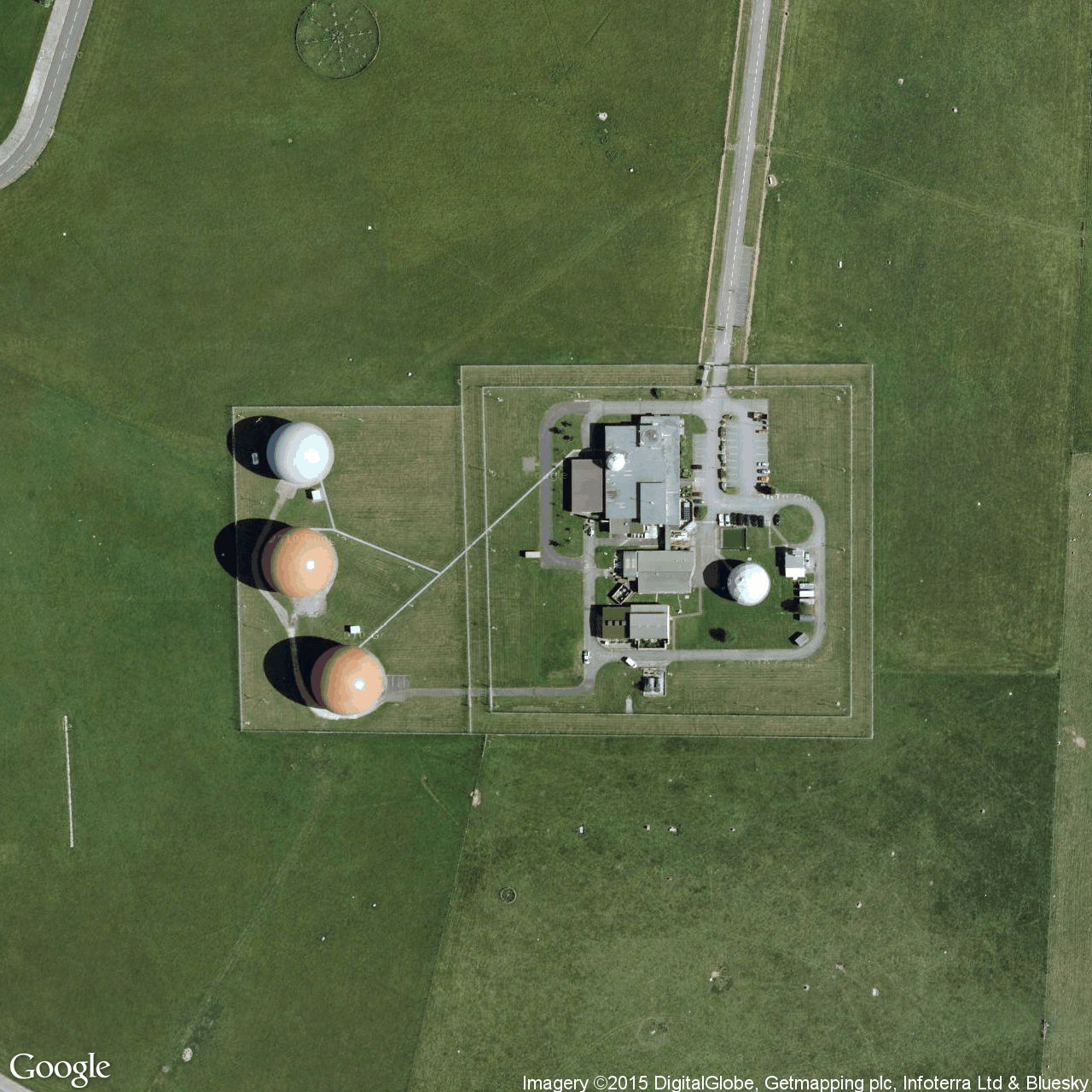

Royal Air Force Croughton, the U.S. Air Force-operated communications installation in England, plays a more ambiguous role in drone operations. On July 22, 2013, the British human rights organization Reprieve filed a complaint with the British government against British Telecom, in which it claimed that the telecommunications giant was contracted to supply a $23 million high-speed fiber-optic cable connecting RAF Croughton to Camp Lemonnier, the American home to drone operations and a major intelligence station in the Horn of Africa. RAF Croughton likely plays a dual role in both the command and control of U.S. drones at Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti and as a relay station for intelligence collected from drones. Like Ramstein AFB, Croughton contains numerous satellite terminal stations that could be used to send instructions from the operators in the United States to the unmanned aircraft.

RAF Croughton is a growing hub for intelligence operations. The U.S. military has decided to spend $317 million on upgrading the British base. The first part of the project will involve moving the operations of RAF Molesworth and RAF Alconbury—two smaller intelligence installations—to Croughton. One of the organizations that will relocate from RAF Molesworth is Africa Command’s J2 Directorate, the department that “manages intelligence collection, analysis, production, dissemination” for U.S. military operations on the African continent. With the additional staff from Molesworth and Alconbury, Croughton will host an even more varied contingent of U.S. and NATO partner intelligence agencies. Even the U.S. State Department’s Diplomatic Telecommunications Service maintains a communications station at RAF Croughton.

Not all the U.S. agencies at Croughton are welcomed by the United Kingdom. In June, Labour MP Tom Watson called for an investigation into the activities of the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency at RAF Croughton based on information gleaned from the Snowden documents. Specifically, Mr. Watson was upset that the Croughton facilities were, according to a November 2013 investigation by the The Independent, being used as a relay station to transmit information collected from a CIA/NSA listening post at the U.S. Embassy in Berlin to a facility in Maryland.

The British Telecom contract indicates a push by the military to create stronger lines of communication between the United States and its overseas installations. One motivation for the fiber-optic project could be that the military leases bandwidth from commercial satellite companies for a large portion drone communications, creating the potential for exponentially larger costs as the quantity of full motion video from drones continues to increase. A January 2013 report by the Defense Business Board argues that more commercial satellite bandwidth will be needed due to the military’s “expanded presence into varied geographies” and an “increasing reliance on surveillance” platforms such as drones. The DBB report notes that by 2020, around 68% of all military satellite communications will be handled by commercial entities. According to the Air Force’s “RPA Vector” report released on February 17, 2014, the high demand for bandwidth is overloading a communications infrastructure that was built largely on an existing architecture and that prioritized the operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. As the U.S. transitions away from Afghanistan, the Pentagon is rebalancing its resources in order to accommodate strategic moves such as expanded counterterrorism operations in Africa and President Obama’s strategic “pivot” to the Pacific.

In the 1950’s, a new breed of aircraft would come to redefine the collection of aerial imagery. On July 4, 1956, a U-2 spy plane took off from Wiesbaden Air Base in Germany and penetrated deep into the Soviet Union, collecting mass amounts of information on Soviet activities. The lightweight and high-flying U-2 was unique due in large part to a simple and adaptable design that could accommodate an array of sensors. The Central Intelligence Agency pioneered the development of the U-2 under the leadership of Richard Bissell and deployed it to multiple air bases around the world from Osan in South Korea to Incirlik in Turkey. From Incirlik Air Base, the U-2 spy planes flew over the Black Sea and as far east as Afghanistan. By the time a U-2 reconnaissance squadron was deployed to RAF Alconbury in England in 1982, the U.S. military had largely assumed responsibility for the U-2 operations.

The bases that housed the U-2s were only one part of an array of facilities around the world where the American military and intelligence community spied on the Soviet Union. In Deep Black: Space Espionage and National Security, William E. Burrows writes that these bases served a variety of functions ranging from listening posts to satellite uplink and downlink centers. As William E. Colby, the former director of the CIA, remarked in a 1983 interview with Burrows, “Overhead reconnaissance has hugely increased our total fund of knowledge of the world.”

While parts of the Cold War network of American intelligence stations like Pine Gap and Menwith Hill still exist, most of those bases are now serving new missions. Where U-2s once took off from Incirlik Air Base in Turkey bound for the Soviet Union, today Predator and Reaper drones conduct reconnaissance and surveillance missions over Iraq and Syria. In Japan, RQ-4 Global Hawk drones have replaced the longstanding U-2s, though the military has suspended the retirement of the U-2 until 2019. RAF Alconbury, another base that was once home to the U-2, will soon be packed up and consolidated with RAF Croughton. Osan Air Base in South Korea is now home to DGS-3, one of the two overseas centers—Ramstein in Germany is DGS-4—for the Air Force’s Distributed Common Ground System.

Drones, like the U-2 in the 1950’s, have enabled the collection of unparalleled quantities of data and have captured military planners’ imaginations for their unique operational qualities. As the Cold War architecture gives way, a new intelligence network emerges, one that is defined by new technologies of surveillance and reconnaissance, real-time collaboration between intelligence collectors and customers, and the volatile international security environment. The introduction of new intelligence capabilities during the Cold War gave rise to a debate over the best uses for those technologies. As the United States transitions from the heavy military commitments in Afghanistan to a more uncertain global force posture, the infrastructure of drone operations warrants closer examination.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]