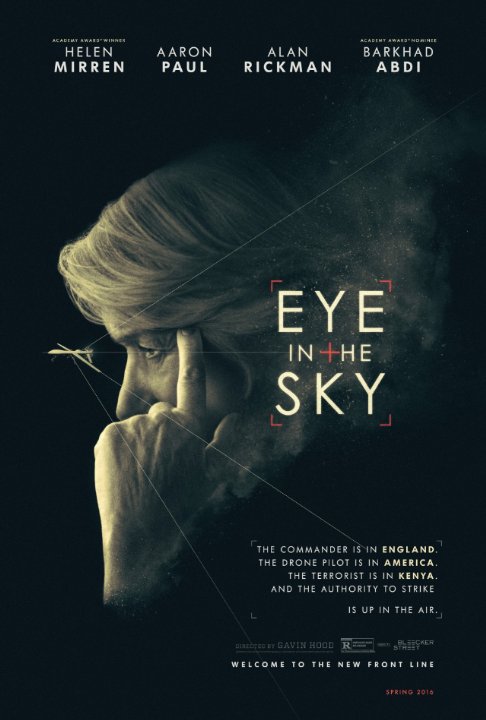

Gavin Hood is an actor, writer and director. His films include Tsotsi, the winner of Best Foreign Film at the 2006 Academy Awards, Rendition, X-Men Origins: Wolverine, and Ender’s Game. His most recent film, Eye in the Sky, follows the story of a number of individuals involved in a drone strike, from those in command to those on the ground. The film, which stars Helen Mirren, Alan Richman, Aaron Paul, and Barkhad Abdi, centers on the decision-making process known as the “kill chain” in a counterterrorism operation, and raises questions about the consequences of drone strikes, as well as the the moral, ethical and strategic dimensions of the targeted killing program. We spoke with Gavin about what he sought to achieve with the film.

Interview by Dan Gettinger

Center for the Study of the Drone Why do you think it’s important for the public to understand the drone technology that’s featured in the film and how the targeting process works?

Gavin Hood Let me start by saying that it’s very interesting when you make a film and you try to predict where technology will be when you finish making the film—bear in mind that we started making this film three years ago. When Guy Hibbert and I started working three years ago, in doing the research, it was both fascinating to us where the technology was but also where it was going. We wanted to make a film that focused on the moral and ethical questions surrounding the use of this technology, which, as you know, is moving forward rapidly. The technology that you see in the film—the Reaper with the Hellfire missiles—is absolutely current and accurate. The Hummingbird, the little bird with the camera, is a technology developed by AeroVironment, a company in Los Angeles, that they had already put up on the Internet five years ago. We spoke with folks at that company and they talked about where microdrones were going, which is where the idea of the Beetle came from. The question of where these microdrones are going is very interesting. We were also afraid that our film may be be out-of-date if, by the time it was released, microdrones had already been weaponized, which is the next phase. One of the reasons we wanted to make the film was to shed some light on where the technology is, where it’s going, but more importantly, the legal and moral and ethical questions that the use of this technology raises.

Gavin Hood Let me start by saying that it’s very interesting when you make a film and you try to predict where technology will be when you finish making the film—bear in mind that we started making this film three years ago. When Guy Hibbert and I started working three years ago, in doing the research, it was both fascinating to us where the technology was but also where it was going. We wanted to make a film that focused on the moral and ethical questions surrounding the use of this technology, which, as you know, is moving forward rapidly. The technology that you see in the film—the Reaper with the Hellfire missiles—is absolutely current and accurate. The Hummingbird, the little bird with the camera, is a technology developed by AeroVironment, a company in Los Angeles, that they had already put up on the Internet five years ago. We spoke with folks at that company and they talked about where microdrones were going, which is where the idea of the Beetle came from. The question of where these microdrones are going is very interesting. We were also afraid that our film may be be out-of-date if, by the time it was released, microdrones had already been weaponized, which is the next phase. One of the reasons we wanted to make the film was to shed some light on where the technology is, where it’s going, but more importantly, the legal and moral and ethical questions that the use of this technology raises.

Drone The White House announced a couple weeks ago that they’re going to release the statistics of the number of people killed in drone strikes. What was your reaction to that news, and what do you think is the legacy that President Obama is leaving office with, in terms of drone strikes?

Hood Well, firstly, I think it’s absolutely essential from a moral point of view that the statistics are known, but also frankly from a strategic point of view. We are engaged, it seems to me, in a battle for hearts and minds, and that is a not a touchy-feely statement. Any counterinsurgency strategist will tell you that if you don’t win the battle—the ideological battle—or the battle for hearts and minds, you will lose the overall battle. If we are using drones without full information of the civilian casualties involved and what the effect of those civilian casualties are on the population in the areas where these strikes are happening, then we are not operating with the full information as a society. If you are seeking backing for this kind of strategy, this targeting of so-called high-value individuals, and if in the use of that strategy civilians are being killed in numbers that we are not aware of, but numbers which many organizations suspect are higher than is being revealed, then you are not offering the public or policymakers all of the information that they need in order to assess whether the use of this tactic is ultimately helpful in terms of winning the overall strategic objective, which is to reduce extremist ideology in the world.

Drone When you started making the film a couple years ago, the U.K. wasn’t really involved in actively carrying out targeted killings. But since then, they have launched drone strikes in Syria, and it has come to light that the U.K. has been involved in U.S. targeted killings in Yemen. Why did you choose to go with the U.K. as opposed to the U.S., and how do you see the U.K.’s involvement in the targeted killing process since you’ve started?

Hood First of all, we obviously designed the film frankly as a thought experiment; it is based on a very specific set of circumstances, it isn’t—these circumstances are not the circumstances of every drone strike. As you know, it is not the case that in every single drone strike the question of whether to fire or to not fire is referred all the way up the kill chain to the foreign secretary, or the prime minister, or in the case of the United States, the secretary of state, secretary of defense, or indeed the president. Depending on the geographical location of these strikes, different rules apply. If you are striking within an already defined conflict zone with clear rules of engagement, in areas such as Iraq or Afghanistan, then sadly this level of debate does not always happen. It very much depends on who is being targeted and where that target is taking place, as to whether the authorization of the strike is referred high up the kill chain.

In our case, in the case of the film, we wanted to create a scenario in which as much discussion as possible was possible within our film. We didn’t want to make a film where the discussion ended at the local commander level. That is a story that can and should be told—the story of the strikes over the tribal areas of Pakistan, for example, where signature strikes take place and where many civilians have been killed—but what we felt was helpful was to make a film which would allow many different points of view to be represented in order to help the conversation that is already underway, but which the public is not necessarily particularly aware of.

In our case, in the case of the film, we wanted to create a scenario in which as much discussion as possible was possible within our film.

Given that the Americans have been doing this for a lot longer, and given that they have this sort of points system in place where they have collateral damage estimates ranging from one to five, and depending on how far up that estimate you go will depend on who you need authority from for the strike, the British, it seemed to us from our research, were still struggling with how to handle these kinds of strikes. We felt that using the British model would allow us to have a more rigorous debate that would allow the public to engage in the kind of moral and ethical question that really has to be discussed. What we wanted to do was not to tell a story where the public could sit back smugly and say, “Oh, well I know what exactly I’m thinking and that’s what I would do,” regardless of what position they took. We wanted to tell a story in which the public would be engaged like a jury, that they would be unsettled, and that they would not know what decision they might take if they were in the position of a drone pilot, or if they were in the position of a politician so that we could hopefully generate a real conversation.

As regards the drone pilots, there are a range of pilots, there are pilots with difficult kills, if you will, under their belt and there are pilots who are pulling the trigger for the first time. Every drone pilot has a moment where they are asked to fire the Hellfire for the first time. Based on our research, that is a difficult moment. It felt to us, having a pilot in that position would allow the audience to imagine themselves in that position and how they might feel, and therefore they would be challenged as to whether they would feel, you know, they could or could not pull the trigger in those circumstances.

Drone Both Eye in the Sky and last year’s film about drones, Good Kill, address this issue of the pilots and the quandary that pilots face. Recently, the Air Force has taken steps to improve pilot morale in the drone crews. Why do you think drone pilots suffer from low morale, and do you think it’s an important part of the conversation?

Hood Well I think that speaking of drone pilots, it’s very difficult to say what drone pilots as a group think, because I mean as with any group of human beings, there’s a range of personalities involved. On the one end you have a small group that is very gung-ho and leaked radio conversations between pilots who will call their targets “bug splats” and who will make very disparaging remarks and dehumanize the targets in ways that I think are both vile from a human point of view, and strategically unhelpful in terms of offering perfect recruiting material for extremists. If pilots talk about other human beings as “bug splats” and dehumanize them, then this is both vulgar and strategically stupid. On the other end of the spectrum, you have a dropout rate of pilots and sensor operators in the drone program that is very high—25 to 30 percent of these younger pilots are dropping out. And the question is, why is that happening? Why do these drone pilots whose lives are not at risk in the way that a fighter pilot’s may be, or a person on the ground—they operate from thousands of miles away—so what is the source of the stress?

Many people say they suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, but there is another term that is perhaps more accurate, and that is perpetration-induced traumatic stress. Most post-traumatic stress disorder arises in situations where an individual—whether that’s in war or in a situation of simply a bad car accident—experiences a moment of extreme distress at the possibility of severe injury or loss of life. These pilots do not face that threat, so what is it that’s causing the distress? The area of perpetration-induced traumatic stress psychology, as I understand it, often examines people who have been involved in torture or the commission of other violent acts in which they are not in danger, but who come to experience psychological distress due to their examination of their culpability in something that may not be favored.

Many people say they suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, but there is another term that is perhaps more accurate, and that is perpetration-induced traumatic stress.

Brandon Bryant, for example, he stayed in the program up to the point at which he took the life of a child and was asked to write up that incident as having killed a dog. His humanity could no longer cope with that way of thinking. That’s a good thing; I do think it’s important that pilots examine their moral and ethical culpability. I don’t think it’s wise to have just gung-ho pilots at the control. Because I do think if you take life, as you point out, in circumstances in which civilians are killed, without serious consideration for the strategic blowback consequences, it is not helpful to have pilots that are very happy to pull the trigger, not from a human point of view and not from a strategic point of view.

Drone In the film, we meet a lot of the key players involved in the operation, but we don’t actually get to know that much about the motivations of the target of the strike, Susan Danford, beyond what you might call her ‘metadata,’ her general characteristics. Was that in order for the audience to replicate the environment of being in the position of somebody who has to make these decisions over whether to proceed with the attack?

Hood It’s a very valid question that you raise. There is no question that it is a valid critique to say that, should we not also have seen the background or the environment of the people being targeted? On the other hand, we don’t really see much of the background of the people targeting either. What we were trying to do in this film was ask our audience, who is by and large a western audience, whether this program is something that they themselves have really thought about. I am not frankly, as a secular humanist, I am not a fan of extremist religious ideology, and I do think it is a real threat. But I do think that even given that I feel that it is a real threat, I think we have to pause before pulling the trigger, and consider a strike from as many points of view as possible.

What I most liked about Guy’s script was giving voice to the innocent victims of these strikes. That is why we put so much focus on the young girl and her family, who are frankly, the people that I am most concerned about from many points of view, both from a humanist point of view but also, again, from a strategic point of view. If this tactical weapon—because a drone is a tactical weapon in a long line of tactical weapons—is used in the way that causes civilians who are not extremists on the ground in these areas to turn against a western, secular, humanist way of thinking, then I think we are going backwards and not forwards. For me, that was the primary question, that was the question that most interested me. Because the question at the end of the film is really what will this father and mother, this child’s parents, what will this child’s parents’ response to the loss of their daughter actually be?

Without getting too political about it, there’s an example very close to home: the response of the African American community to the killing by police officers of young black men is understandably extreme anger at the system that allowed that to happen. If we can see that kind of blowback happening in our own country, what do we think is the kind of blowback that might be happening in areas where drones are used on a weekly basis to eliminate targets, but where we know that civilians have been killed? That is why it is so important for the administration to release the figures, so that organizations such as your own, and the ACLU, and Reprieve, and indeed the military themselves can make a proper assessment of the effectiveness of this program.

That is why we put so much focus on the young girl and her family, who are frankly, the people that I am most concerned about from many points of view, both from a humanist point of view but also, again, from a strategic point of view.

Drone We’re co-teaching a class about drones this semester, and I’m wondering what you thought our students should take away from the film?

Hood I would just say that, all I would ask students to take away is a similar thing to what you would take away from engaging in a discussion about the traditional trolley experiment. The film is really the trolley problem on steroids. I have a law degree and, as a young lawyer, I remember the trolley problem in an ethics class. The fundamental purpose of that thought experiment is to humble young lawyers or ethicists into understanding that problems need to be looked at very, very closely, facts matter, gathering as much information as possible about a particular strategy or problem is essential, and jumping to easy answers is both arrogant and unhelpful and potentially strategically dangerous. What I like about the film is that it doesn’t tell you what to think. It doesn’t mean I don’t have views—it was difficult for me in some ways to tread that line between what do I think and how do I encourage my audience to think, and not tell them what to think.

Some people might critique the film and say, “Well you didn’t take a strong enough point of view, one way or the other.” And that’s a valid critique, depending on your point of view. What I hope to do, and what I think we’ve been successful in doing, is getting people to talk and having them discuss with educators in an environment where they can really delve more deeply into the subject than you can in our few hours, getting them to talk about the questions that the film raises. Leaving it open was a deliberate strategy in order to encourage people to have a conversation rather than to present them with one point of view which they either accept or reject. I feel that so much of our politics has become, as I said earlier, so binary—”I’m right, no, you’re right”—as opposed to, “I have a point of view, you have a point of view, if we get these two points of views, we might arrive at a third point of view,” so that’s what I hope students take away from it. That they are encouraged to engage in conversation and debate.

For updates, news, and commentary, follow us on Twitter.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]