By Chanterelle Menashe Ribes

Auschwitz Overlooked

As aerial sensor technology proliferates, Harun Farocki’s film Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1988), which interrogates our capacity to see freely in a world of mass-produced and computer-produced imagery, is a film worth revisiting. This visual essay opens with the story of German innovator Albrecht Meydenbauer. After almost dying in an attempt to measure the façade of a cathedral, he developed photogrammetry as a substitution for life-threatening hand measurement. “It is a fact [proven] by experience,” Meydenbauer later writes of scale pictures, “[that] one does not see everything, but one sees many things better than on the spot.” Accordingly, he continues, “the capacity to see better is the reverse side of mortal danger.” It is safer, Farocki suggests, to see many things ‘better,’ than to see everything on the spot; our ability to see some things clearer also blinds us.

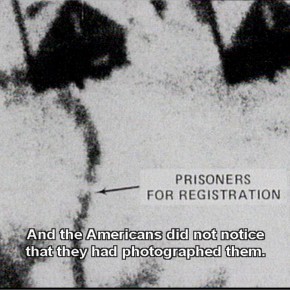

The film’s main focus is an aerial photograph of the Nazi IG Farben rubber plant, taken by an American reconnaissance plane in 1944. Two decades after the photo was taken, CIA analysts realized that it had inadvertently captured the Auschwitz concentration camp. The evaluators surveying the photograph identified a number of indexes of the presence of the camp—the most harrowing of all, prisoners’ footsteps in the snow. The Allies’ failure to see the camp was not a fault of analysis, as they possessed the forensic knowledge to identify it. It was rather that, as Farocki would have it, “they were not under order to look for Auschwitz, and so they did not find it.”

The film’s main focus is an aerial photograph of the Nazi IG Farben rubber plant, taken by an American reconnaissance plane in 1944. Two decades after the photo was taken, CIA analysts realized that it had inadvertently captured the Auschwitz concentration camp. The evaluators surveying the photograph identified a number of indexes of the presence of the camp—the most harrowing of all, prisoners’ footsteps in the snow. The Allies’ failure to see the camp was not a fault of analysis, as they possessed the forensic knowledge to identify it. It was rather that, as Farocki would have it, “they were not under order to look for Auschwitz, and so they did not find it.”

Farocki suggests that a gaze constructed from the ideology of war is as blinding as it is piercing. In this instance, the gaze is foregrounded in a military ideology whose primary objective is to find and bomb targets. If everything in a photograph is uniformly and persistently present, then the photograph itself does not determine the viewer’s gaze or interpretation. When an image is looked at in a prescribed way, everything is not always present to us (even though it is incontrovertibly present in the photograph) and thus it is not always seen. It is our complicity in a certain kind of viewership that dictates what and how we see.

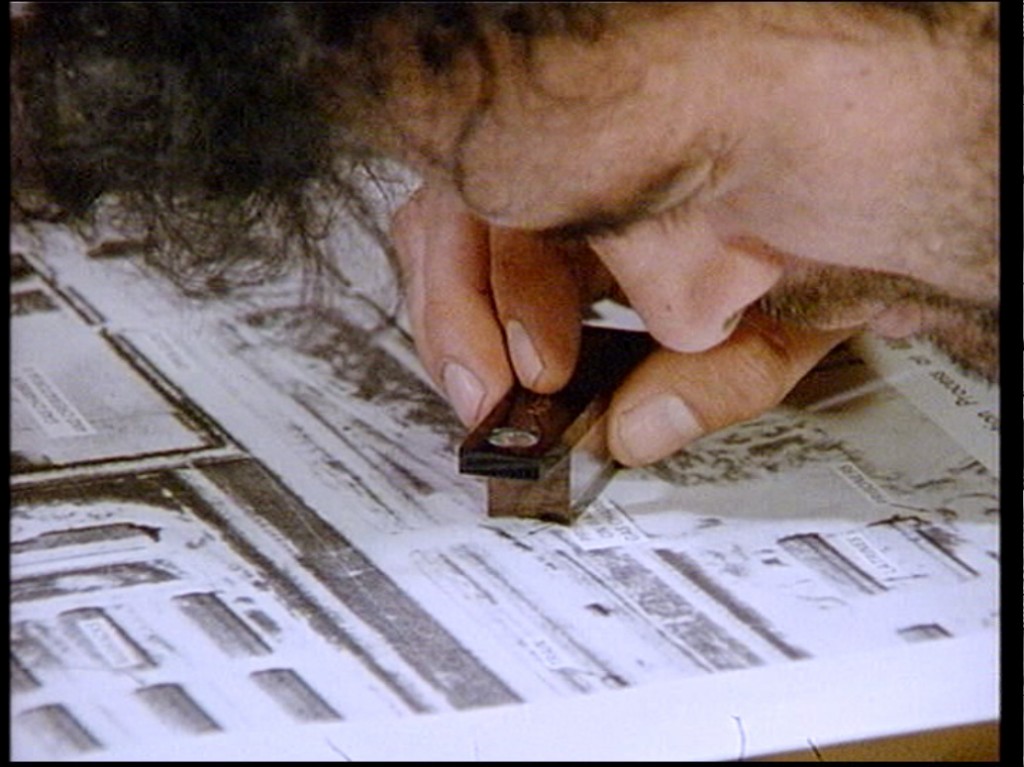

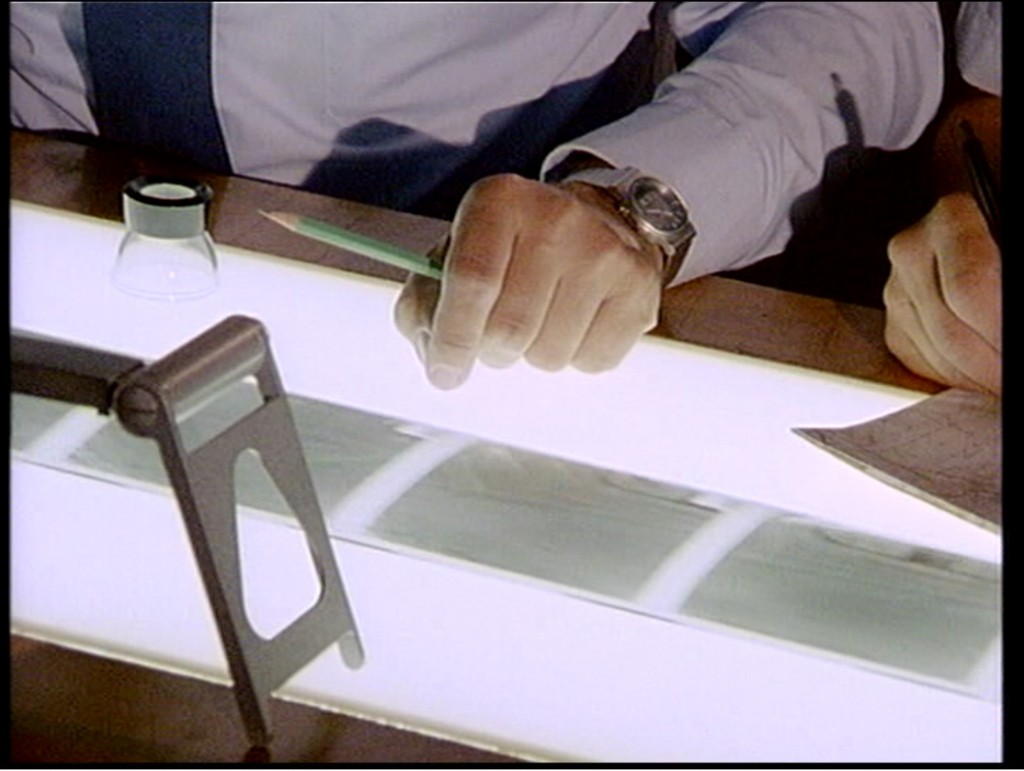

During World War II, the military began equipping bomber planes with cameras to improve the efficacy of the bombing runs. The aerial photographs captured by these planes would preserve what they had helped to destroy. After a plane returned from a mission, analysts pored over the aerial photographs in search of targets: military bases, landing strips, and industrial plants. Seeing in this context of wartime ideology meant using forensic knowledge to evaluate a photograph after the fact, in search of what that ideology dictated one to see. It would seem, then, that the gaze does not come from any kind of psychological or individual desire that influences what is found; instead, it is fundamental and basic in nature. This thereby enabled an ideologically predetermined system of collective viewing to function as a mechanism of war, and not as a visual modality.

The Gaze and Democratization

Images contributes a helpful perspective to the discourse surrounding the democratization of the drone and the aerial view, given that more aerial photos are gazed at now than in any other point in history. In a discussion with the Center for the Study of the Drone, the curatorial duo Yael Messer and Gilad Reich discussed the public’s desire for the view from above and its status as an inherent “position of power.” Its genealogy, they explained, is bound by its earliest usages to institutions of power and knowledge. Our desire for democratic access to the aerial view lies tantamount to our desire for this power. It would follow, then, that having democratic access to the view from above puts us in this position of power. But Messer and Reich are wary to suggest that this access automatically engenders its reappropriation. Accessibility “redistributes” the view from above but may not actually shift the power dynamic as much as we’d like to think.

It is by no means a given, Reich and Messer suggested, that accessibility to the aerial position will give us the right kind of power. Reappropriative actions are motivated by our mistrust of the institutions of power. But there is nothing to say that this power will operate differently in our hands than in the institutions in which it has persisted, especially if it has only ever persisted in the grip of these institutions.

Furthermore, Reich explains, aerial images “seem to have an objective quality—but [are] more complicated than that.” Images, he explains, are “tricky,” and can fool the inexperienced viewer into seeing something that is not there, implying that “objectivity” is more contingent upon how something is viewed than who is viewing it. However, if we apply Farocki’s logic, the ‘trickiest’ part about these images may not be that they can be easily misread by the amateur. It is rather that democratic access to the view from above and the rapid increase in the manufacturing of images that comes with it highlights, rather than mitigates the fact that we may be just as complicit in prescribed viewing as the Allies were.

Furthermore, Reich explains, aerial images “seem to have an objective quality—but [are] more complicated than that.” Images, he explains, are “tricky,” and can fool the inexperienced viewer into seeing something that is not there, implying that “objectivity” is more contingent upon how something is viewed than who is viewing it. However, if we apply Farocki’s logic, the ‘trickiest’ part about these images may not be that they can be easily misread by the amateur. It is rather that democratic access to the view from above and the rapid increase in the manufacturing of images that comes with it highlights, rather than mitigates the fact that we may be just as complicit in prescribed viewing as the Allies were.

Farocki demonstrates the extent to which ideologically constructed gaze dictated intentionality, to a point where an establishment of murder was overlooked. If we equate accessibility to drone technology with its reappropriation, then we create viewership that prescribes itself with this power. That is, though we may not think so, we still see and take images according to some ideology or other. We want to reappropriate the aerial view because we mistrust the way its being used now, but this assumes that in our hands, the aerial view will be useful, powerful, and different, which isn’t necessarily true. Images of the World and the Inscription of War shows us how destructive this can be, despite intentions. Reappropriative ideology will dictate what we see in the same way that military ideology caused the Allies to miss Auschwitz. Though these ideologies and objectives differ in nature, they still make the same kinds of mistakes.

The Coded Eye

Later in the film, Farocki predicts that there will be “more pictures of the world than the eyes of the soldiers are capable of evaluating…more pictures than [their eyes] can consume.” This prediction has come true. Now, we largely rely on computers to analyze our images. The question of the determined gaze has become even more important as images are increasingly analyzed according to code. As Farocki points out, a computer analyzing images will only ever find what it is programmed to look for, and will never unintentionally find something that doesn’t fall into its criteria. Computers, he notes, turn images into numbers. The computer is incapable of the kind of reevaluation that permitted the CIA to spot Auschwitz.

Farocki would likely note that more images are being taken during this period of “democratic” access to drone technology than we are capable of evaluating. Ironically, this makes the images prone to never truly being seen (or reevaluated), rendering them statically facile. True democratization of the aerial view will only be achieved if we recognize that finding something unseen does not necessarily come with the production of new images, but rather with the reevaluation of the old ones. In acknowledging that our view of the image differs from what it captures, we can begin to redefine our relationship to the images we already have and approach those that have yet to be taken with greater consciousness and care.

Photo credit: stills from Images of the World and the Inscription of War by Harun Farocki.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]