On the morning of September 3, 1914, an aerial observer by the name of Lieutenant Watteau assigned to the Paris garrison rushed to the Deuxième Bureau, the French military intelligence agency, with urgent news. In the four weeks since the outbreak of World War I, German armies had advanced to within 30 kilometers of the center of Paris. The French government had fled the city and the British-Franco armies were retreating under the pressure of the German right flank. At the Paris headquarters, aerial observer Lieutenant Watteau reported a 48-kilometer gap between the First and Second German Armies on the far right flank of the advance. The following day, more Parisian airmen confirmed the German mistake, convincing French and British commanders to halt their retreat and to drive a wedge between the German armies. In the First Battle of the Marne, French and British forces reversed the German encirclement of France—known as the Schlieffen Plan—and a long and costly war began in earnest. With advances in aviation, communication and photography, the First World War not only was the dawn of aerial warfare, but also the emergence of a sophisticated aerial reconnaissance and intelligence apparatus. It was a conflict in which, as the cultural theorist Paul Virilio writes in War and Cinema, aviation ceased to be about breaking flight records and became “one way, or perhaps even the ultimate way, of seeing.”

Prior to the First World War, balloons were the main platform for military aviation. During the Second Hague Peace Convention in 1907, Russian delegates encouraged a ban on the launching of projectiles from balloons. Captain William Crozier of the American delegation objected to the proposed unlimited ban on aerial warfare. Crozier argued that while the technology at the time did not allow for aerial targeting, perhaps new technologies in the future might add forward mobility to aircraft. Machine powered aircraft might enable more precise methods for launching projectiles from the air, thereby precipitating a speedy conclusion to the conflict and sparing lives.

The delegates decided to reduce the period of the ban from indefinitely to until the next peace convention. The possibility of an air war excited public attention. In 1908, H.G. Wells published The War in the Air, in which massive fleets of bombers wreak “civil conflict and passionate disorder” on the urban centers below. The first aerial bombardment occurred three years later, during the 1911-1912 Italo-Turkish War, when Italian Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti threw four grenades out of his Etrich Taube monoplane from an altitude of 600 ft.

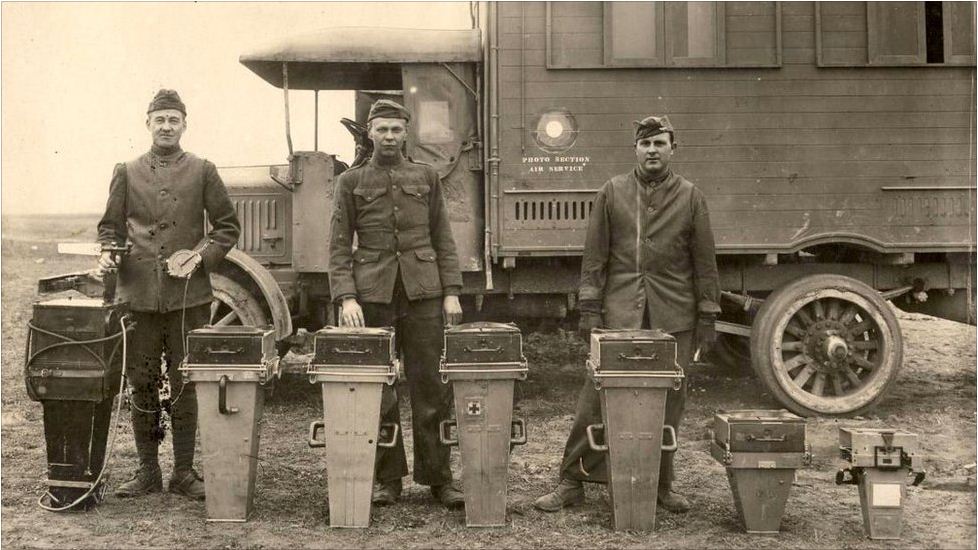

By this time, sophisticated aerial photography from kites, balloons and even pigeons had already developed significantly thanks to a century of experiments by scientists and militaries. In “The Balloon Prospect,” Caren Kaplan writes that balloons were used for military reconnaissance as early as June 26th, 1794, when the French Revolutionary Army floated balloons over their engagement with the Austrian-Dutch coalition in Fleurus, Belgium. Aerial reconnaissance from balloons also saw use in the American Civil War, the Spanish-American War, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and in the Boer War. Balloons and other methods of aerial photography began to give way to airplanes in the Italo-Turkish War, in which aircraft were used for the first time for military reconnaissance, directing naval gunfire. At the 1913 Paris Aero Salon, French engineers revealed the first airplane to be equipped with a specially configured aerial camera. By 1914, each of Europe’s major powers had developed dedicated aircraft corps for aerial intelligence. “The single use in war for which the machines of the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps were designed and the men trained was (let it be repeated) reconnaissance… [I]t was designed to operate with an expeditionary force and to furnish that force with eyes,” wrote Walter Raleigh in The War in the Air: In Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force (1922).

In Shooting the Front: Allied Aerial Reconnaissance in the First World War, Terrence Finnegan argues that reconnaissance aircraft—not fighters or bombers, which remained fairly rudimentary—were the focus of military aviation in the First World War. Allied powers dedicated resources to developing technical capabilities in aerial photography, photo interpretation, and aerial targeting for artillery, as well as a system for disseminating intelligence to the commanders in the field. Finnegan argues that systematic adoption of the aerial photograph led the First World War to become the first time that technical forms of intelligence collection became more highly valued than information gathered from human sources.

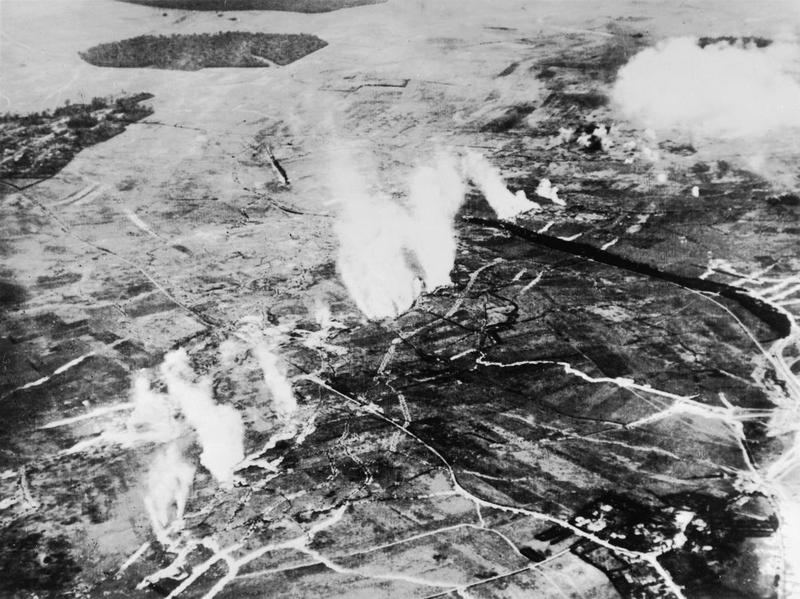

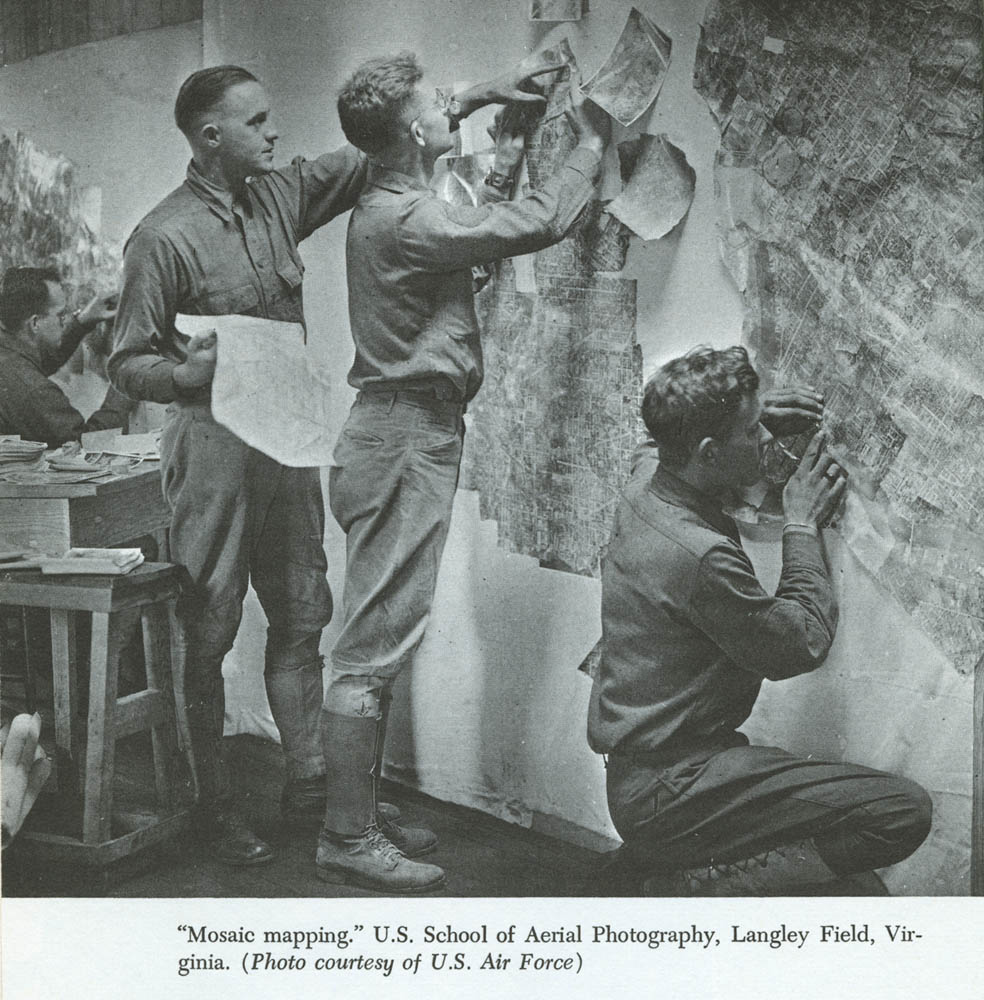

Aerial imagery was first used comprehensively to plan an engagement in the early months of 1915. At the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, British intelligence distributed 1,500 photographic maps of the German trench fortifications to British infantry commanders and, for the first time, aerial observers coordinated artillery barrages with an infantry advance. Despite being a strategic failure for the Allies, the engagement demonstrated the increasing sophistication of imagery interpretation and exploitation techniques for intelligence and cartographic purposes. Mosaic maps, which became an important tool throughout the war, were made by taking a series of overlapping vertical photos and aligning them together to create a comprehensive view of the enemy’s trench network. In the same way that an analyst today might use drone imagery to develop a “pattern of life” analysis based on behavioral signatures, photo interpreters in the First World War used stereoscopes—a device used to view two separate images—to make comparative studies of the imagery. “The interpreter is trained to know how things ought to look under all sorts of different conditions in a vertical photo,” wrote Harold Porter in Aerial Observation, in 1921. Interpreters looked for visual clues that might denote changes in the enemy’s position. For example, soil displacement or shadows could help identify trenches, embankments, artillery batteries and troop movements.

As the war became an entrenched battle of attrition, a system for the collection and dissemination of aerial intelligence facilitated increased coordination between the operations of aircrews and ground units. Artillery units in particular soon came to rely on aerial intelligence for the effective targeting of enemy positions. Artillery, the most lethal weapons platform of the war, served a number of duties that ranged from weakening enemy fortifications to disrupting rear-echelon communications and logistics. Equipped with the details of their targets, “aerial coverage provided a sense of control and purpose to artillery staffs,” writes Finnegan in Shooting the Front. In order to be relevant to ground operations, military intelligence required that photographs be delivered as fast as possible. Prior to the 1916 Somme offensive, British air crews conducted “speed tests,” challenging each other for the fastest time between taking a photograph and delivering it to a frontline unit. During the Verdun Campaign of 1916, the French assigned air crews to support specific units of artillery and infantry as aerial sentries, providing a stream of coverage during engagements. “Observation planes now guaranteed with the greatest exactness the operation of liaison with the infantry, of the photographic service, and of the timing of the artillery,” wrote Marechal Petain in Verdun, in 1930. Wireless telegraphy and emerging technologies such as radio provided close to real-time information, aiding coordination between aircrews and ground forces.

Coordination between air and ground, often the decisive factor in later conflicts and in military engagements today, became so common that infantry units came to associate the presence of aircraft with an impending artillery barrage. One German soldier at the Battle at Verdun in June 1916 described the psychological impact of the air-ground cooperation: “A silent enemy flyer pursued the individual wanderer, and French artillery shells accompanied his path. To run, stand still or lay down, it was all the same.” Despite being a technology primarily for aerial reconnaissance, the aircraft acquired a deadly reputation in the First World War as the harbinger of artillery strikes. In a 1917 article for the New York Times, Orville Wright argued that when the United States sent to Europe enough airplanes to bring down every German reconnaissance airplane, “the war will be won, because it will mean that the eyes of the German gunners have been put out.” Wright illustrates the violent bond between aircraft and artillery as well as to the essential function of the aircraft to provide the power of sight in a war in which soldiers charged blindly to kill and to be killed. The fusion of ground operations and aerial intelligence, predicated as it was on a vast intelligence collection, analysis and dissemination bureaucracy, was the first iteration of what today is known as a “kill-chain.”

Footage from the 1919 film of the Western Front by Jacques Trolley de Prévaux, a French Navy pilot who, during the Second World War, played a crucial role in the Resistance gathering intelligence for the Allied invasion of Normandy.

The beginnings of the drone are remarkably similar to that of its manned predecessor. Just as ground troops in the First World War were rendered sightless by the static trench warfare and oppressive new weapons, soldiers in the counterinsurgency wars today face an enemy that hides among the civilian population. While drones existed long before the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, unmanned systems were embraced by the American military due in part to the difficulties of waging counterinsurgencies. These factors lead commanders to rely on aerial photographic or video imagery in order to increase an awareness of the battlefield and to find enemy targets. The introduction of new platforms on such a scale not only changes the kinds of intelligence that are collected but also influences the planning and conduct of military operations. In recent years, aerial intelligence has begun to focus more on tracking individuals and recording their habits in a “pattern of life” analysis, departing from its role in coordinating the bombing campaigns seen in the second half of the 20th century. While the tempo of the counterinsurgency campaigns of today do not match that of the First World War, the global search for terrorists by drones flashes the same sense of a forever war.

At the outbreak of the First World War, commanders like British Field-Marshal John French believed that no mechanical platform would ever replace cavalry as means to conduct reconnaissance. Within months, however, the horse succumbed to industrial warfare, as did traditional methods of cavalry generalship. In the place of cavalry arose the modern military intelligence bureaucracy that employed a Fordist system of photo interpretation in an attempt to achieve total knowledge of the battlefield and total control. The power of photo interpreters, in the words of Paul Saint-Amour, was “not in the mere ability to command, but in the more rarefied capacity of producing the knowledge that would inform the commanders.” With the proliferation of the drone there is the unshakable feeling that our means of perceiving the world are drastically changing. Those who witnessed the aircraft’s rise to prominence in war must have felt something very similar. The emergence of the drone on foreign and domestic fronts recalls the earliest days of aviation when, as Paul Virilio writes in The Art of the Motor, the ambition “was not so much to fly as to see from on high.”