By Arthur Holland Michel and Dan Gettinger

2015 was a very busy year in the drone world. The U.S. domestic commercial drone industry began to take shape, military drone exports grew significantly, the technology advanced in leaps and bounds, and certain public safety concerns became a hotly debated topic. We like to track drone news closely as it happens; as we roll into 2016, we looked back at the last year of happenings in the drone world. Here are the most important drone stories of 2015.

Personnel Challenges In January, the Daily Beast reported that the U.S. Air Force’s drone operators were at “breaking point.” According to a memo and several USAF sources, the Air Force did not have enough pilots and operators to meet the Pentagon’s demands for surveillance flights, which had increased as a result of the fight against ISIS. A few days later in a press conference at the Pentagon, Air Force Secretary Deborah James and Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Welsh announced several changes to the program: they said they would increase monthly incentive pay for pilots, pull in personnel from the National Guard and USAF Reserve, and extend mission assignments for pilots. In May, the Air Force announced that it would cut the number of drone combat air patrols from 65 to 60 to lift pressure from drone crews. (Each combat air patrol consists of four Reaper or Predator drones.) In July, the Air Force announced that it would begin offering drone pilots cash bonuses to stay with the program. Pilots with at least six years experience will be eligible for bonuses that range between $75,000 to $135,000 depending on the length of the commitment.

In December, The Los Angeles Times reported that the U.S. Air Force is considering a $3 billion expansion of American drone operations. The plan calls for more aircraft, 3,500 additional personnel, and new outposts at Air Force bases across the country. If implemented, the expansion would help the Air Force meet the demand for drone capabilities and reduce pressure on existing personnel. It would reverse the earlier plan to cut the number of MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper CAPs from 65 to 60. A few days later, the USAF revealed that it will allow enlisted personnel to pilot the RQ-4 Global Hawk, a high-altitude long-endurance surveillance and reconnaissance drone. It will be the first time since the Second World War that non-officers will be permitted to fly USAF aircraft.

We took a close look at the USAF’s drone personnel reforms and their history: here’s what you need to know.

Drone Strikes Although the number of reported U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan were down in 2015 from 2014, the number of strikes in Yemen and Somalia rose slightly in 2015 over the previous year. Meanwhile, in Syria, the United States has relied on drones to carry out a campaign of targeted strikes against the Islamic State. A number of high-level militants were killed in 2015 as a result of these strikes. In Somalia, U.S. drones were reportedly responsible for strikes that killed Yusef Dheeq, the head of al-Shabab’s external operations division; Adnan Garaar, the alleged ringleader of al-Shabab’s 2013 Westgate Mall attack in Nairobi; and Abdirahman Sandhere, a senior commander in al-Shabab. American drones have also been active in Yemen where the U.S. carried out a series of strikes against al-Qaeda in the Arab Peninsula. On June 17, U.S. officials reported that Nasser al-Wuhayshi, the leader of AQAP, had been killed in an American “signature strike,” an operation that targets individuals based on patterns of behavior rather than known identities. In Pakistan, drone strikes largely targeted members of the new regional Islamic State branch. However, the number of reported strikes is much reduced from previous years, perhaps due in part to the mistaken killing of American and Italian hostages by CIA drones in January.

Over the year, we wrote a number of articles about drone strikes. In February, we took a look at the global network of communications that undergird American drone operations in Yemen and the Horn of Africa. In April, we examined the strategy of high-value targeting and, in May, we looked through translated documents from Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad to find references to drones. In the summer, we spoke with Max Abrahams about the impact that drone strikes have on terrorist organizations and wrote about the role that American special forces play in conducting targeted strikes.

In September, we dived into the Royal Air Force’s reports of its engagements in Iraq and Syria to examine the role that armed drones are playing in the conflict. Part of this study took a look at the high-value individuals like Junaid Hussein and Mohammad Emwazi that the U.S. and Britain are targeting with drones.

Drone Proliferation Foreign interest in arms-capable U.S. drones grew significantly in 2015. A report by the Australian Senate foreign affairs, defence and trade committee urged the Ministry of Defence to purchase armed drones. In an interview with the Telegraph, U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron said that he will double its fleet of MQ-9 Reaper drones. The 20 new drones, known as Protectors, will be used to target the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. Prior to 2015, the U.S. had strict limits on the sale of military drones to other countries, even its close allies. In February, the Department of Defense stated that it would sell four General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper drones to the Netherlands for $339 million. The Netherlands will join NATO partners Britain, France, and Italy in flying the Reaper. That same month, the U.S. State Department loosened restrictions on selling American-made drones to foreign militaries, ending the ban on exporting armed drones. In a statement on its website, the State Department said that some rules, such as a prohibition against selling drones to countries that intended to use drones to “conduct unlawful surveillance or use unlawful force against their domestic populations,” would remain in place.

Non-U.S. armed drones also saw action in the field in 2015. In September, Pakistan announced that it had used a locally produced drone known as the “Burraq” (which is thought to be passed on a Chinese unmanned aircraft) in its first lethal drone strike. Then, in December, in the first known lethal strike by a Chinese-made drone, an Iraqi military CH-4 drone launched a strike against suspected ISIL militants in Ramadi. Iraq acquired the Caihong-4, a Chinese strike drone that resembles the U.S. MQ-9 Reaper, earlier this year. In the 2015 edition of a yearly report on China’s military capabilities, the Department of Defense told Congress that China will manufacture up to 42,000 military drones for its military and for export by 2023.

In March, we wrote a guide to the new export policy and, in November, we compiled a comprehensive review of the significant deals for military drones that were completed last fall. And as China continues to become a power player in the global drone market, we published a briefing on Chinese military drones.

Presidential Drones In January, a DJI phantom quadcopter drone crashed on White House grounds. Shawn Usman, the owner of the drone, was reportedly test-flying in downtown Washington D.C. when the machine malfunctioned. Prosecutors later cleared Usman of all charges, as they determined he was not in control of his drone when it crashed; he may in fact have been asleep. In response to the White House drone incident, drone manufacturer DJI said that it would introduce software changes that will keep drones out of restricted areas. Using a system known as “geofencing,” software installed on DJI’s drones will prevent users from flying their aircraft near airports, restricted areas like Washington, D.C., prisons, power plants, and other locations. The company updated and expanded its geofencing software in November.

In response to the White House incident, the U.S. Secret Service began testing different methods for defending the White House against drones. The tests, which took place over several weeks in D.C. between 1 a.m. and 4 a.m., included methods for tracking, hacking, and jamming incoming drones. In Japan, a man was arrested for landing a drone carrying trace amounts of radioactive material on the roof of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s office in April. Yasuo Yamamoto, 40, who turned himself in to police, was protesting Japan’s nuclear energy policies.

Although drones and targeted killing have received almost no attention so far in the presidential elections, it is an issue in which the next commander-in-chief will need to play a direct role. We looked at every candidate to find out their opinions on drones and targeted killing.

NPRM and other Regulations In February, the Federal Aviation Administration released its long-awaited proposed rules for the domestic, non-recreational use of drones weighing less than 55 lbs. The rules, which would require commercial drone pilots to acquire an operator’s certificate and maintain visual contact with the aircraft, among other requirements, would not apply to hobbyists or recreational users. The FAA then opened the proposed rules to a public comment period, and we compiled a list of questions that they especially wanted the public to address. In September, the FAA updated the rules governing recreational model aircraft. In the new version of the regulations—Advisory Circular 91-57A—the FAA emphasized that recreational users must comply with airspace rules such as Temporary Flight Restrictions, and warned that hobbyists who fly recklessly or endanger manned aircraft may be subject to enforcement actions. As the U.S. awaits comprehensive rules for drone use, some local governments are seeking to pass laws limiting the use of unmanned aircraft. In December, the FAA issued a fact sheet addressing how state and local governments may and may not regulate drone use.

Some of the largest U.S. drone companies are based in California. This year, the state narrowly avoided enacting a significant drone bill, S.B 142, which was passed by the state congress but vetoed by Governor Jerry Brown, would have placed greater restrictions on drone use than any other piece of state legislation. The story of S.B. 142’s life and death is a window into the ways in which states are trying to limit drone use, as well as the measures that the the drone industry is taking to protect itself from onerous regulations.

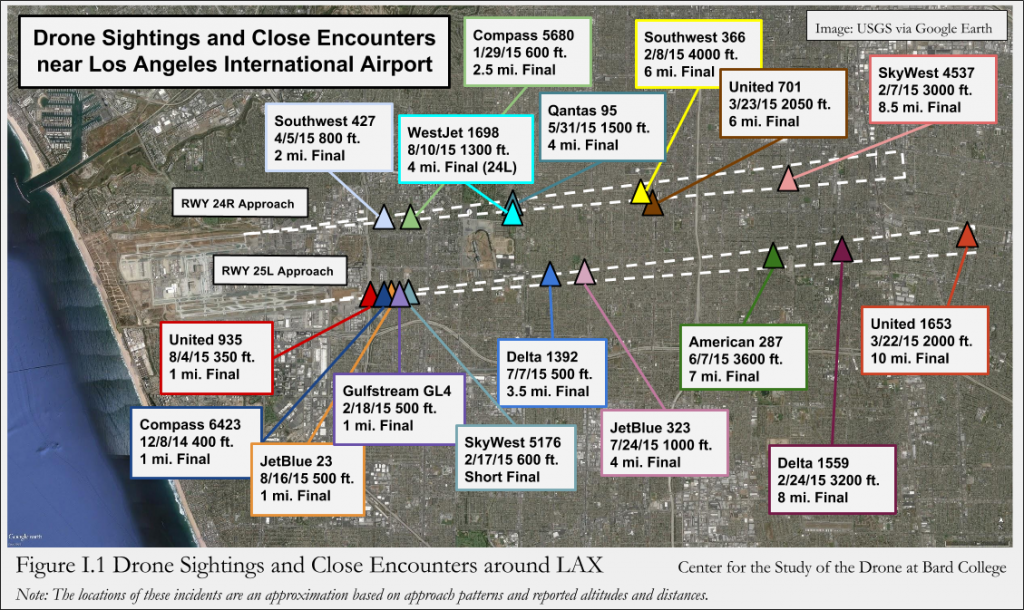

Close Encounters and Other Incidents In 2015, potentially hazardous incidents involving drones became a major topic, widely debated by stakeholders and regulators. In January, the FAA issued a guide for law enforcement agencies on how to handle encounters with drone hobbyists. The 12-page document offers suggestions to police on the best methods for investigating individuals suspected of endangering the national air space. In late February, CBS revealed that the Federal Aviation Administration was investigating a spike in the number of drone sightings by pilots of manned aircraft. According to the news report, there were on average two reported sightings every day for the first few weeks of the year, far more than during the same period in 2014. Reports of close encounters between drones and firefighting aircraft became increasingly common, too. In the first publicized incident of this type, in June, a hobbyist drone reportedly interrupted efforts to contain a wildfire near Big Bear Lake in California. The pilots of an air tanker loaded with flame retardant claimed to have spotted a drone flying at 11,000 ft. above the blaze, which resulted in the mission being aborted. Within a month, drones had already interrupted firefighting efforts on at least four other occasions in southern California, a Forest Service spokesperson told Reuters. Several incidents also occurred at ground level. In one such incident, in September, a child was injured in a drone crash in Los Angeles.

In August, the Federal Aviation Administration announced that reports of near-misses between drones and manned aircraft had increased up significantly this year. The FAA said that it had received reports of 650 incidents up to July, more than double the total number of incidents in 2014, and explained that multiple investigations into drone operators who fly too close to aircraft were underway. At an aviation industry summit in October, an FAA official stated that as many as one million drones could be sold in the holiday season.

Given the growing number of incidents involving drones in the airspace, we published “Drone Sightings and Close Encounters: An Analysis,” which examines over 900 incidents involving drones and manned aircraft in the national airspace. We found over 300 potentially dangerous incidents in 2014 and 2015, 90 of which involved commercial jet aircraft. This is the most comprehensive and detailed study of these incidents published to date. In an op-ed for The New York Daily News, we argued that while drones are bringing new dangers to our airspace, the solution does not involve stricter regulations and enforcement, but rather collaboration between all stakeholders.

Drone Attack Concerns and Drone Countermeasures In August, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security issued a bulletin to all law enforcement agencies warning that drones could be used as weapons in attacks. According to a copy of the bulletin obtained by CBS News, the recreational and commercial uses of drones “underscore potential security vulnerabilities… that could be used by adversaries to leverage UAS as part of an attack.” We published a guide to understanding the potential threats posed by drones and the countermeasures that are under consideration.

In response to some of these concerns, 2015 saw a number of companies developing anti-drone systems that specifically target small unmanned aircraft in both military and domestic settings. In March, aerospace company Exelis unveiled Symphony, a system for tracking drones that fly under 500 ft. In May, three British companies unveiled an anti-drone system that can detect, track, and bring down drones at a range of up to five miles, and defense contractor Controp unveiled a radar capable of detecting small drones. In June, the Russian military claimed to have successfully developed a microwave gun capable of disabling aerial drones from up to six miles away. That same month, defense contractor MBDA Germany claimed it tested a high-powered anti-drone laser, destroying a small drone at a range of 500 meters, and a consortium of French and British companies said it was developing a system that can detect and track a small drone from up to five nautical miles away, and even locate the drone’s operator.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Army revealed that it is developing a chain gun for shooting down small enemy drones. At the U.S. military’s 2015 Black Dart exercises, contractors tested a variety of anti-drone systems. At the exercises, Boeing demonstrated its 2 kilowatt anti-aircraft laser system, shooting down a small target unmanned aircraft in mid-flight. Shortly thereafter, the company demonstrated a portable version of its laser, which it claims could also be used to bring down small drones. Not all of these measures are kinetic. A team at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology claims to have developed a sound cannon that disables small drones from distances of over 100 ft. A German startup has unveiled a system that uses various sensors to detect and track small drones at a range of about 300 ft., while British-Italian defense company Selex ES unveiled a system for tracking and taking control of rogue small drones. Airbus Defence and Space also announced that it is developing a system to track and jam small drones at distances of up to six miles. Even the FAA is exploring ways of using technology to prevent drone users from flying near airports and restricted areas. During a House Transportation Subcommittee on Aviation hearing, FAA Deputy Administrator Michael Whitaker said the agency had partnered with CACI International to develop a system to force down wayward drones.

Swarms Interest in drone swarms—that is, when multiple drones work collaboratively and autonomously—swelled in 2015. In January, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency announced that it will be looking to develop a system to allow a single pilot to operate multiple drones at once in denied airspace. In April, the U.S. Navy’s Office of Naval Research announced that it had begun testing a drone swarm system called LOCUST. (In an interview with Vice, the technical manager of the U.S. Navy’s LOCUST swarming drone project describes the system and its level of autonomy). Meanwhile, a company called Queen B Robotics has demonstrated a system that allows you to to fly commercial drones in swarm-like formations. And the U.S. Army conducted tests with swarms of consumer drones to evaluate both the offensive applications for the technology and the threat they might pose if used by an adversary.

LAWS In April, the United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons held a Meeting of Experts to discuss the ethical, legal, and humanitarian implications of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS), a hotly-contested topic. Some member states were pushing for an international moratorium on LAWS, while others are hesitant to ban a technology that still does not exist. The Meeting, which was attended by delegates of member states, as well as a variety of NGOs and think tanks, reflected a diversity of opinions and policy agendas.

We published a helpful guide to the positions of each of the participating countries in the CCW conference on LAWS. We also put together a definitive postgame analysis of the conference.

In June, in an open letter from the Future of Life Institute, over 1,000 scientists and researchers called for a ban on “offensive autonomous weapons.” The signatories included physicist Stephen Hawking, philosopher Noam Chomsky, and technologist Elon Musk. According to the letter: “AI technology has reached a point where the deployment of such systems is—practically if not legally—feasible within years, not decades.”

Registration In a bid to try and better track the recreational use of drones in the U.S., the Department of Transportation announced in October that it was developing rules that will require all drones to be registered. In a press conference, Secretary Anthony Foxx told reporters that the DOT would work with a task force comprised of representatives from the Federal Aviation Administration, the unmanned aircraft industry, commercial airline pilots, and others in order to release the rules by the end of the year. In December, after receiving a comprehensive set of recommendations developed by the task force, the Department of Transportation and Federal Aviation Administration announced a national registry for drone users. Under the new rules, all drone users will need to register aircraft weighing more than 250 grams with the FAA or face a range of stiff civil and criminal penalties. Individuals who already own drones must register by February 19, 2016. In an op-ed for The Daily Dot, we examined the FAA’s new drone registration rule, contending that it is an understandable measure even if it doesn’t end up making a difference. The Federal Aviation Administration reported that in the first two days since its drone registration system was opened, 45,000 drone users signed up.

Sense-and-avoid and UTM Significant progress has been made in the development of technologies that would enable the safe integration of unmanned aircraft into the airspace. In February, NASA and the FAA announced that they had conducted successful tests of a proof-of-concept sense-and-avoid system for large drones, which allows unmanned aircraft to autonomously prevent mid-air collisions. By September, the project, a collaboration with contractors General Atomics and Honeywell, had passed a the third phase of testing. The tests included more than 200 live scenarios in which NASA’s Ikhana drone detected and averted a possible collision with another aircraft. Meanwhile, a European program is underway to create sense-and-avoid technologies.

NASA is also developing an air traffic management system for drones, called Unmanned Aerial Systems Traffic Management (UTM). In June, NASA announced that it was working with Verizon to develop cellular-based system for monitoring drones in airspace. In July, NASA held a convention for companies and experts to develop concepts for its UTM System. In a paper released at the conference, Amazon urged the FAA to segregate airspace below 500 ft. into zones of “low-speed localized traffic” for recreational users and “high-speed transit” for commercial users, and Google proposed that unmanned aircraft traffic control be outsourced to private providers instead of the FAA. The development of NASA’s air traffic management system, which began live testing in November, will include testing of four generations of prototypes over the next few years.

Several commercial drone companies have developed collision avoidance systems for smaller drones. At the Consumer Electronics Show in January, Intel demonstrated a sense-and-avoid system for multirotor drones. Drone company PrecisionHawk unveiled a cellular-based tracking and avoidance system that can be installed on drones, while a startup called XactSense has announced that it is developing a highly autonomous drone that navigates using a LIDAR laser system. In November, a PhD candidate at MIT unveiled a stereo-vision-based obstacle detection system that allows drones to navigate their surroundings at up to 30 mph without crashing into anything. And in December, Draganfly Innovations, a U.S. drone maker, has integrated an ADS-B transponder, which is used to track aircraft and prevent mid-air collisions, on a small multirotor drone. Meanwhile, at around the same time, defense contractor Lockheed Martin exhibited a traffic management system for unmanned aircraft flying at low altitudes.

Exemptions and Pathfinder This year, the U.S. domestic commercial drone industry took flight. Prior to 2015, the FAA had only approved a handful of companies to fly drones commercially. By the end of the year, 2,672 approvals had been issued. In March, in the first FAA-approved use of drones for newsgathering, CNN took to the air above Selma, Alabama in anticipation of the 50th anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery civil rights marches. Meanwhile, the government approved Amazon’s request to test its delivery drone system in the United States (The approval came one week after Amazon criticized the FAA’s rulemaking process in a U.S. Senate hearing.) Also in March, the FAA announced that it had significantly streamlined the approval process for commercial drone exemption applications. Under the new rules, commercial users that had already received approval from the FAA would be allowed to fly anywhere in the country, so long as the drone stays under 200 ft. and away from restricted areas like airports. In May, the Federal Aviation Administration announced that it was launching a new program, called Pathfinder, to explore how drone regulations might accommodate emerging technologies, such as systems that permit flights beyond visual line of sight.

As the rate of FAA commercial drone exemptions grew, we have maintained a comprehensive database of companies and individuals with an exemption. This database offers the most detailed view to date of the emergent domestic commercial drone industry. We found that exemptions have been issued to a remarkable variety of companies across many industries. Meanwhile, the FAA has sought to make clear that it will not turn a blind eye to non-approved commercial drone use. In October, it fined a Chicago-based company $1.9 million for flying drones for profit without permission. The fine was the largest that the FAA had ever levied against a drone operator.

Arrivals and Departures Two large technologies companies joined the drone industry in 2015. In February, Samsung announced that it will open a new lab to develop drones, along with a range of other future technologies. And in July, Sony created a company that will offer aerial imaging services with drones of its own design. Sony later released a video of a prototype of its new fixed-wing drone, which can take off vertically and fly at over 100 mph. Meanwhile, in November, Torquing Group, a much-publicized startup that produced a micro-drone called the Zano, announced that it had gone out of business. The Zano was initially funded on European Kickstarter, setting a record by raising more than $3.4 million.

Hydrogen Power One of the key limitations of small drones is battery life. Hydrogen power may be the solution. In April, Singapore company Horizon Energy Systems announced that it had developed a lightweight hydrogen fuel cartridge for use in drones, while a Canadian company called EnergyOr created a hydrogen fuel cell that enabled a quadcopter drone to fly for three hours and 43 minutes without landing, a new record for small drones. In July, defense contractor Israel Aerospace Industries and Florida company Cella Energy won a grant to develop a hydrogen fuel cell for drones.

High Altitude Drones Unmanned aircraft have already revolutionized war and commerce, but now a new breed of ultra-high-altitude aircraft capable of remaining airborne for extensive periods of time—perhaps even years—are set to bring new capabilities to both the battlefield and a range of industries. In November, U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron announced plans to field a high-altitude long-endurance surveillance drone for surveillance operations. Though Cameron did not mention the drone by name, it is thought to be the Airbus Zephyr solar-powered unmanned aircraft. Here’s our briefing on the capabilities and applications of high-altitude drones.

New Technologies This year saw a range of exciting new technologies and innovations that could have profound impacts on the future of unmanned technologies. In February, Portuguese company Tekever demonstrated a system for controlling drones using only your mind. In December, engineering students at Texas A&M University developed a system to operate drones thousands of miles away over the Internet. The team demonstrated the system by piloting several drones in Australia from a basketball court in Texas. Meanwhile, a team at Rutgers University has developed a multirotor drone that can both fly and swim.

On the military side there were a number of significant technology stories. In April, the U.S. Navy’s X-47B stealth combat drone autonomously refueled itself from an aerial tanker. After the test, the Navy retired its two X-47B prototype unmanned combat drones. Known as Salty Dog 501 and Salty Dog 502, these remarkable aircraft are the most advanced and most autonomous drones ever made. Among many other firsts, the X-47B was the first drone to autonomously land on an aircraft carrier. We recounted their remarkable story. In August, defense contractor Lockheed Martin announced that it was developing a possible replacement aircraft for its U-2 high-altitude surveillance plane, which is currently at risk of being phased out from the U.S. Air Force in favor of the Global Hawk, a high-altitude drone. Lockheed Martin later confirmed that it is developing an unsolicited proposal for an unmanned successor to its U.S. Air Force high-altitude surveillance and reconnaissance jet, the U-2 Dragon Lady.

In a statement at the Bundestag, Katrin Suder, the secretary of state for the German Ministry of Defense, told party leaders that Germany and France plan on partnering with Italy to develop a medium-sized armed military drone by 2025. Secretary Suder said that the three countries hope to formalize the agreement later this year. The defense ministers of France, Italy, and Germany will sign a Declaration of Intent for a two-year study for a joint medium-altitude long-endurance military drone project. In December, the German Defense Ministry announced that it is assuming the leadership role in the development project.

And in a surprising turn of events, the U.S. Marine Corps canceled the Legged Squad Support System program. Developed by Boston Dynamics, a Google-owned robotics company, the LS3, also known as the robotic mule, was a highly publicized autonomous mechanical pack animal, capable of carrying up to 400 lb. of supplies and gear.

Drone Deals and Investments In May, venture capital firm Accel Partners invested $75 million in Chinese drone maker DJI. A couple of weeks later, the two companies announced that they had set up a $10 million fund to support the development of unmanned and robotics technologies. In October, the Shenzhen-based company announced that it would open a large R&D facility in Silicon Valley (The company makes the most popular commercial multirotor drones; in April, it unveiled the Phantom III, the latest incarnation of its now-iconic Phantom quadcopter series.) Meanwhile, Intel Corporation invested more than $60 million in Yuneec Holding Ltd., a Hong Kong-based company that manufactures consumer drones. “We’ve got drones on our road map that are going to truly change the world and revolutionize the industry,” Intel CEO Brian Krzanich said in a video presentation on the company’s website.

Drone Racing The first U.S. National Drone Racing Championship took place at the California State Fair grounds In July. Australian Chad Nowak took home the gold. Stephen Ross, the owner of the Miami Dolphins football team, investing $1 million in Drone Racing League, a New York-based company that hopes to become a world leader in drone racing competitions. In a short video, the New York Times took a closer look at this fast-expanding sport.

Humanitarian and Environmental Drones In February, the first ever UAE Drones for Good competition took place in Dubai’s Internet City. Participants submitted case studies of a range of potentially beneficial applications of drones, from wildlife conservation to emergency medical assistance. The winning drone, developed by Swiss company Flyability, was designed for rescue missions in confined spaces. Meanwhile, researchers in Norway began using drones to measure the effects of climate change. Following the earthquakes in Nepal in April, drones were used to map the damage. In May, in the wake of widespread flooding in Texas and Oklahoma, a group of researchers from Texas A&M University — Corpus Christi received approval from the FAA to use drones in support of search and rescue operations. In July, rescue teams used a drone to carry a lifejacket to two boys who were stranded in the middle of a river in Maine. Meanwhile, activists in South Korea are reportedly using drones to smuggle items into North Korea, and the New York Times used a drone to capture aerial footage of how climate change is impacting the Marshall Islands.

Drone Art And finally, in 2015 the drone made many appearances in the art world. In April, the famous graffiti artist KATSU used a spray can-equipped drone to vandalize a giant billboard in New York City. Melbourne, Australia was treated to a drone opera. Drones, Muse’s latest album, was released in June. Ethan Hawke starred in Good Kill, a drama about the trials and tribulations of a U.S. drone pilot. There were many spectacular drone videos released in 2015; in one that was particularly notable, photographer Ryan Deboodt flew a drone into an enormous cave in Vietnam.

Images by Dan Gettinger.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]