By Arthur Holland Michel

In 1916, the 1st Aero Squadron of the U.S. Army crossed the U.S. border into Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa. Their mission was to provide aerial reconnaissance for General Pershing’s cavalry force. It was the first time the United States used aircraft in support of a military action. The operation was plagued with technical difficulties and adverse weather conditions; only two of the original eight aircraft returned to Texas. Today, almost one hundred years later, a fleet of unmanned aircraft operated by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) surveil the same remote landscape over which some of America’s first aviators made history. The CBP drones represent the federal government’s most sustained and substantial domestic drone program.

Just as in the early days of manned aviation, the Southern borderlands have not been exactly hospitable to the prospects of unmanned flight. Since the first test flight in 2004, the CBP’s drone program has been rife with operational challenges and political controversies. A recent Department of Homeland Security report on the CBP’s drone operations concluded that the drone program isn’t worth the time or cost. Here’s what you need to know about the CBP drones:

- The Office of Border Patrol, a subset of the Department of Homeland Security’s Bureau of Customs and Border Protection, started thinking about drones when it launched an ambitious remote sensing project in 1998 called the Integrated Surveillance Intelligence System—ISIS. The idea was to create a virtual border fence by erecting poles with cameras along the most high-trafficked areas of the border. Much of the thousands of miles of U.S. land borders is in remote or inaccessible areas. Remote sensing systems—that is, systems that could gather data without having a human physically present at the controls—were deemed an obvious solution to this problem.

- The ISIS program was plagued with technical difficulties and cost overruns. A 2005 report by the DHS Office of Inspector General criticized the CBP at length for failing to develop any metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of the program. In 2006, after spending $439 million, the DHS cancelled ISIS due to comprehensive system failures. In 2011, SBInet—the successor to ISIS—was also cancelled after a critical DHS review of the $1 billion program. In these reports, drones were proposed as a possible alternative to fixed sensor stations due to their endurance and mobility.

- After a year of planning, the CBP first tested a drone over the southern border between June and September 2004. The CBP used an Elbit Hermes 450, an Israeli-made, medium-sized reconnaissance and surveillance UAV. In a November 2004 report of the tests obtained by MuckRock, David V. Aguilar, then chief of the Border Patrol, concluded that while the drones were neither as operationally effective nor as cost effective as a manned helicopter, they could still be a justifiable purchase because of the future potential of unmanned aircraft. The Predator drone was estimated to be 4.6 times more expensive per flight hour than the Hermes 450 and 10 times more expensive than the Astar Helicopter. (This was not, incidentally, the first time the U.S. flew drones along its borders. According to Richard Whittle in Predator: The Secret Origins of the Drone Revolution, in 1995 a Predator drone was briefly used in a counter-drug exercise on the southern border.)

- The first CBP Predator took flight along the border with Mexico in October 2005. It crashed into a hillside near Nogales, Arizona in April 2006 after the contractor flying the aircraft shut down its engine mid-flight. An National Traffic and Safety Board investigation of the crash—the first ever investigation into an accident involving an unmanned aircraft—found a number of technical and operational problems with the CBP drone program.

Customs and Border Protection maintains a fleet of nine General Atomics Predator B and Guardian drones. The program is operated by the CBP’s Office of Air and Marine (OAM).

- Three aircraft are based Sierra Vista, Arizona, three are based in Grand Forks, North Dakota, and three are based in Corpus Christi, Texas. In November, 2012, the CBP proposed the acquisition of 14 additional drones at a cost of $443 million.

- The drones are used “to conduct missions in areas that are remote, too rugged for ground access, or otherwise considered too high-risk for manned aircraft or personnel on the ground.”

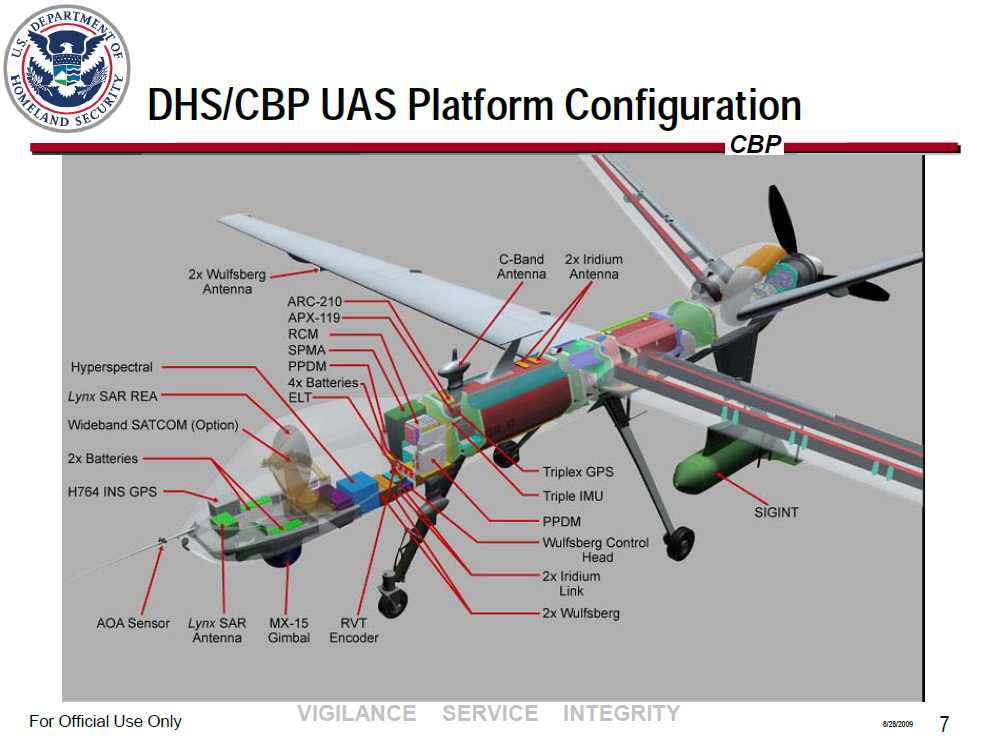

- The CBP drones, which fly at altitudes between 19,000 ft. and 28,000 ft., are equipped with a sensor suite that includes and electro-optical and infrared camera. The sensors allow the CBP to collect footage in day or night, as well as track the movement of vehicles such as cars and boats and gather terrain information. At the minimum altitude of 19,000 ft., the CBP claims that its sensors are not powerful enough to discern a person’s physical characteristics or read a license plate. The CBO also notes that its sensors cannot see through walls.

- One of the CBP drones is equipped with a Wide Area Surveillance System, which is mounted on the wing of the aircraft. This system allows the CBP to record an area approximately 3.7 miles wide.

According to a Government Accountability Office report published in September 2014, CBP drones are used for three roles:

- Patrol: drones fly on routine patrols, looking for the illegal crossing of goods or people across U.S. borders.

- Investigations: drones are used to “provide aerial support for law enforcement activities and investigations”

- Disaster response: drones are used to support emergency response to disasters such as wildfires and flooring. Drones can be used to assess the extent of damage and aid in the planning of disaster response.

While the border patrol drones fly primarily along the southern border, the CBP also stations drones in North Dakota and Florida.

- According to the the Government Accountability Office report, between Fiscal Year 2011 and April 2014, 80% of drone flights occurred along border or coastal areas. The CBP clocked 18,089 hours on its drone fleet during this time: 57% of these flight hours took place over the southern border, 18% took place over the Northern border, and 7% took place over the Southeast maritime border.

- The CBP drones are not used exclusively for border patrol. According to that same GAO report, of the remaining 20%, CBP drones flew 1,726 flight hours, or 9% of the total hours, over “restricted and foreign airspace.” Another 1,594 flight hours represented training, transit, and disaster response operations.

- CBP offers its drones for air support missions to other agencies within the Department of Homeland Security, such as the Drug Enforcement Agency, as well as other Federal Agencies, such as the FBI. A 2013 investigation by the Electronic Frontier Foundation found that between 2010 and 2012, CBP drones flew 500 flights for other U.S. law enforcement agencies and sheriff departments. According to a detailed Privacy Impact Assessment produced by the DHS, in such operations CBP drones could, for example, “conduct surveillance over a building to inform ground units of the general external layout of the building or provide the location of vehicles or individuals outside the building. When flying a UAS in support of another component or government agency for an investigative operation, CBP may provide the other agency with a direct video feed through access controls or with a downloaded video recording of the operation.”

- In January, 2014, CBP pilots operating one of its “Guardian” variants of the Predator drone off the coast of San Diego, California detected a malfunction and decided to ditch the unmanned aircraft in the ocean. Parts of the drone, which had been based in Arizona, were later recovered by the Coast Guard.

In a report published on May 30, 2012, the DHS Office of Inspector General concluded that the CBP drone program was poorly organized and needed to be better planned to maximize its resources. The report noted that the CBP needed to improve its coordination efforts with other agencies, especially with regards to obtaining reimbursements for costs incurred during operations in which CBP drones were used by other agencies.

On December 24, 2014, the Department of Homeland Security published a report based on an audit of the CBP’s drone operations. The report concludes that the CBP drone program does not perform to expectations and is not worth the cost. The report notes that:

- The CBP drones are supposed to be airborne for 16 hours every day. In 2013, the aircraft were only airborne for about 3.5 hours per day, on average. The CBP notes that it does not fly its drones in severe weather, high winds, or when there is cloud cover.

- The CBP could only attribute “relatively few” apprehensions of illegal border crossers to its unmanned aircraft operations.

- The CBP could not demonstrate to the auditors that the use of drones has reduced the cost of border surveillance. The CBP had predicted that the use of drones would reduce the cost of border surveillance by 25% to 50% per mile.

- The CBP drones did not prove that they were able to reduce the need for Border Patrol agents to respond to incidents on the ground.

- The CBP drones focused primarily on just 170 miles of the the 1,993-mile Southwest border.

- The audit found that in 2013 the CBP drone program cost $62.5 million.

The authors write in the conclusion of the report, “Given that, after 8 years of operations, the UAS program cannot demonstrate its effectiveness, as well the cost of current operations, OAM should reconsider its planned expansion of the program. CBP could put the $443 million it plans to spend to expand the program to better use by investing in alternatives, such as manned aircraft and ground surveillance assets.”

Documents and Reports

- 2004 Study of CBP UAV Tests in Arizona

- 2005 DHS Office of Inspector General report on ISIS remote-sensing surveillance program.

- 2006 DHS UAS/UAV Technical Specifications

- 2007 NTSB investigation of the 2006 CBP Predator drone crash.

- 2010 CBP Concept of Operations Report for drone operations.

- 2011 DHS Review of SBInet program.

- 2012 DHS Office of Inspector General report on CBP drone program.

- 2013 Investigation into the loans of CBP drones to other agencies by the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- 2013 DHS Privacy Impact Assessment for the Aircraft Systems

- 2014 CBP Report on the crash of a Guardian UAV.

- 2014 Government Accountability Office report on CBP drone program 2011-2014.

2014 DHS Office of Inspector General report on CBP drone program.

Cover image: Nick Oza/The Republic

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]