When Does an Animal Become a Drone?

By Austin Considine

Call it a sign of our weird times: Last month, around the same time Iran claimed to have captured a small American spy drone, officials in Sudan captured a strange flying thing of its own: a living vulture, outfitted with a GPS tracking system and what the Sudanese claimed was a camera that could beam its pictures back to Israel.

According to a Dec. 8 story in a state-supporting Sudanese newspaper, a tag affixed to the bird’s ankle read “Israel Nature Service” and “Hebrew University Jerusalem.” It included the email address of Ohad Hatzofe, an avian ecologist for the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. Sudanese officials claimed the vulture was an Israeli spy: not quite a drone, but something like one—a low-cost means of international espionage by most moral economies.

In an interview with CNN, Hatzofe was quick to deny that the bird—a Griffon vulture, endangered in the Middle East—was a spy. The equipment was to study its migratory patterns. “The GPS gear on these vultures can only tell us where the birds are, nothing else,” he said, adding later: “I’m not an intelligence expert, but what would be learned from putting a camera onto a vulture? You cannot control it. It’s not a drone that you can send where you want. What would be the benefit of watching a vulture eat the insides of a dead camel?” The Israeli government declined comment.

Spy or not, the emergence of a competing, conspiracy-tinged narrative was telling: Like rumors of dynamited levies in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, or United States government collusion in the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the counter-narrative offered by Sudan said a lot about the weird, discorporeal world we’re living in—and the myriad means powerful people have devised to rule their subjects through stealth, paranoia, imagination and a little help from nature.

Alexander’s Elephants, Skinner’s Pigeons

The Israeli vulture may not actually have been doubling as a spy drone. But the Sudanese interpretation isn’t so outlandish. Humans are effectively turning animals into war-related technology everywhere you look.

In some respects, we’ve always done it. Alexander the Great used elephants to terrorize and trample his enemies, a tactic he adopted after having been, himself, terrified by them in the hands of his Persian adversaries. Horses have been an integral part of warfare since at least the ancient Sumerians, bestowing military advantage wherever people had mastered them—from the Mongolian hoards that marauded Asia and Eastern Europe, to the fearsome Comanche, legendary warrior-horsemen of the American Great Plains.

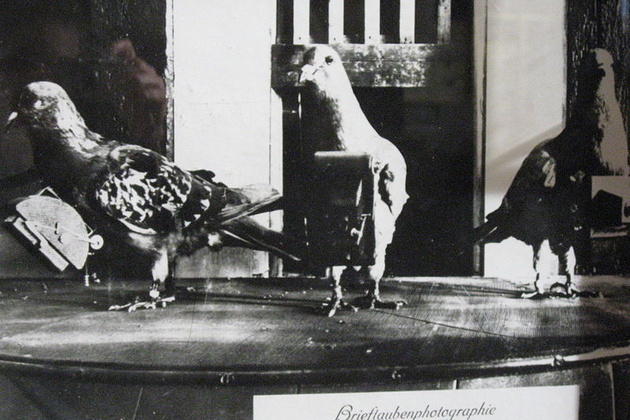

The age of using animals as tanks evaporated soon after the advent of real tanks, as the Polish cavalry learned when faced Hitler’s invading panzers on horseback in 1939. But humans weren’t done using animals for military and defense purposes. They were good for transmitting information, for example: Carrier pigeons were used to transmit messages as early as the 6thCentury B.C.E., by King Cyrus of Persia and remained in use through World War II.

There was another, more creative way to use animals, however: as bomb delivery. Author Mike Davis notes in his book Buda’s Wagon: A Brief History of the Car Bomb that history’s first “car bomb” was arguably a horse and carriage, sent straight into the heart of New York’s Financial District in 1920, loaded with hundreds of pounds of dynamite and cast iron, and exploded in front of the J.P. Morgan headquarters on Wall Street, killing 38. It also killed the horse, an unwitting kamikaze.

As Motherboard noted last year, famed behaviorist B.F. Skinner devised a plan during WWII for training pigeons to pilot missiles directly to their targets. Skinner’s idea—which, in test runs, did surprisingly well—was to mount a camera to missiles and put a pigeon and a monitor inside. Pigeons were trained to recognize on-screen targets and to use up-down and left-right controls to keep the image centered, guiding it to its destination. The idea was ultimately scrapped in favor of early electronic guidance.

Had the project come to full fruition, how might we have thought about the pigeon-piloted aircraft? Most people value pigeon’s lives less than the lives of humans. But do we value them the same as a hard-drive? Would we swerve the car to avoid hitting a microchip? What distinction do we draw between a computer-controlled drone and what might best be described as an animal-controlled drone?

Some Animals Are More Equal than Others

The answer, in short, depends on where we draw the line between animals we care about and animals we don’t.

Before the word “drone” acquired its contemporary meaning to describe a pilotless aircraft, the word simply referred to a male worker bee or, more figuratively, to an idler or lazy worker (drawn from the fact that drone bees produce no honey). That original use of the word is one of many things that made the Los Alamos National Laboratory’s Stealthy Insect Sensor Project so intriguing. The program effectively turned bee drones into bomb-sniffing drones.

There’s something creepy about appropriating an insect for our purposes. “When there’s a biological entity that’s involved, it tickles a feeling of disgust or causes us to think twice,” saidJonathan Moreno, a bioethicist and multi-disciplinary professor at the University of Pennsylvania. “But I think that has to do with deep evolutionary reactions to yucky things.”

Pardoxically, however, the yuckier an animal is, the more apt we probably are to be okay with appropriating them. Like dogs, domestic honeybees are capable of sniffing out some volatile organic compounds (VOCs) down to parts per billion. Like dogs, they’re perfect candidates for bomb detection. Unlike dogs, they aren’t fluffy, cute or loyal.

Perhaps more importantly, researchers at LANL note, honeybees have a few solid advantages over dogs when it comes to bomb-sniffing. For starters, they are also a lot cheaper. They can be trained in a matter of hours to respond to a specific scent by sticking out their tongues, which is, in turn, detected by electronic sensors encasing the bees.

But there’s a good chance those advantages wouldn’t suffice to pass public muster if they belonged to baby snow seals. Bees have stingers, segmented bodies and insect brains. Putting a bee in harm’s way somehow seems morally safer because we don’t want to cuddle them.

“We love bees when we can get honey—we love them to death,” Moreno said. “But we don’t like them when they interfere with our picnic.”

We seem to feel at least nominally the same about rats and mice. Sure, they’re furry. But we also compete with them for space and they spread disease, Moreno noted. In November, Agence France-Presse reported that an Israeli defense contractor had developed a technology that used mice for bomb detection in airports. Rather than sending mice on bomb-sniffing missions, the technology actually incorporates the mice into the machines, same as a gear, a wire, or a circuit.

The system, developed by the Herzliya-based BioExplorers, is simple: A traveller stands inside a small booth and is hit by a gentle blast of air that is then sucked into an small opaque chamber, where a group of eight mice are on duty.

After eight seconds, assuming the subject is all clear, a green light appears and the barrier opens. But if the air smells of a suspicious a material the mice have been trained to detect, they gather in the so-called reporting compartment, which raises an alarm.

The developer said the idea first occurred to him while in the Israeli army. Mice, he determined, would be a great alternative to bomb-sniffing dogs. The advantages were logistical, he told AFP: Dogs can be intrusive, intimidating and don’t actually smell as well as mice.

Dogs can also be heavy and clumsy, putting them in danger on certain kinds of bomb-sniffing missions. Other, less dangerous animal-based alternatives exist. APOPO, a Tanzanian-based company founded by a Belgian product designer and rat-lover, uses rats to sniff-out land mines—in part because they are too light to set them off.

Technology is helping us remove other animals we like from the defense equation. Late last year, the U.S. Navy retired a half-century-long program that employed dolphins to do its underwater mine-sniffing. The dolphins were replaced with a fleet of unmanned “Knifefish” robots that are cheaper over time, don’t need training, and can go on scouting missions for 16 hours at a time. They have also never starred in 1960s TV shows, aren’t much fun at the zoo, and aren’t very exciting airbrush subjects for an eight-year-old girl’s sweatshirt.

The dolphins were formidable helpers while under the navy’s employ. They did a lot more than just stick out their tongues, like bomb-sniffing bees. As Greg Thomas wrote:

The Navy had 80 bottlenose dolphins and 30 California sea lions in the ranks, ready to deploy from their base in San Diego, as of 2010. According to a Seattle Times report in 2003, the animals only sweep for and detect mines. When they find one, they are trained to drop a transponder nearby, the report says. More recent reports show that the role of dolphins is actually much more involved in disabling mines, recovering neutralized mines and even planting live mines, and also patrolling waters for enemy divers. When they find a live mine, dolphins are trained to attach a small explosive to it and swim away.

Despite their cleverness (or, perhaps partly because of it), putting Flipper in harm’s way was never popular with groups like the Humane Society, which has welcomed the program’s end. “We have been saying for so many years that they’ve got to work on technology to replace live animals,” said Naomi Rose, a marine mammal scientist for the Humane Society, in an interview with Raw Story last month. “The ethical concerns about putting these animals in combat situations or any kind of patrolling where any negative interaction with enemy divers could occur… is very troubling.”

When Does a Living Creature Become a Robot?

While we strive to remove animals we like from danger by replacing them with robots or more efficient, less cute, less risk-prone animals like rats and mice, we’re also hijacking the brains of simple creatures we revile, like cockroaches and roundworms. Could therein lie a broadly acceptable future for animal-based defense technology?

Last fall, researchers from Harvard and from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in New York successfully used lasers to take over the brains of small, transparent roundworms about a millimeter in length, called Caenorhabditis elegans. The worms have only the most rudimentary nervous systems, consisting of just 302 neurons (the human brain, by comparison, has about 86 billion).

Researchers described being able to make the worm turn left or right by remote control. They were able to make it do loops and were able to trick it to think that there was food nearby. “We want to understand the brain of this animal,” said Harvard’s Sharad Ramanathan, an assistant professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard and one of the experimenters, in a press release. They wanted to “essentially turn it into a videogame,” he added, “where we can control all of its behaviors.”

Not only lasers, but also magnets have been used to control worms. Earlier last year, scientists from the State University of New York in Buffalo were able to trigger the same kind of roundworm’s instinctive reaction to heat using magnets after having genetically re-engineered its neurons.

Perhaps most impressive of all—and most promising in the realm of defense-drone technology—is our newfound ability to control cockroaches by remote control. Using a tiny electronic backpack, electrical engineers at North Carolina State University were able to make cockroaches move forward by stimulating a sensor at their rear that senses predators. With electrodes attached its antennae they were able to control whether it moves left or right.

Researchers say the development may be an alternative means of getting tiny “robots” into impossibly small spaces—a difficult task in the past because they needed prohibitively large power sources.

“Insects have a power process on them, a natural one,” said Alper Bozkurt, an electrical engineer at NCSU, in an interview with NBC News. “We just needed to supply power for communication, which is not much.”

Such radio-controlled roaches could, as the NBC article notes, be used for things like search-and-rescue missions following earthquakes.

They could also be used for spying. Roaches are much more controllable than, say, the Israeli vulture accused of espionage by the Sudanese. (No stopping for unplanned snacks on dead carcasses to impede its mission.) They are also much simpler creatures, which arguably makes taking over their brains more ethical than than hijacking complex creatures that may have some sense of subjectivity—what, in human terms, we would call consciousness.

“I don’t know what the subjectivity of a cockroach is like,” said Moreno, the bioethicist. “I don’t think that there probably is any there at all. So, there, when you’re just taking over their distributive brain… you’re controlling reflex actions. And when you do that with a rat, there’s probably some subjectivity of some kind.”

What distinction remains between a robot and an insect that’s become manipulable by remote control? That probably depends on your politics and your religion. But perhaps, as Moreno suggests, it’s the spying itself we should be more worried about than whether it’s being done by an insect or a robot.

“There’s a certain convergence here between nanotechnology and insects, between biological little creatures and non-biological little creatures,” he said. “There are people… working on little, tiny drones working in swarms. So are those less creepy than using the bees?”

A version of this story originally appeared on Motherboard.

The author can be followed on twitter at @AustinConsidine

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]