This feature is based on an essay presented by the author at “Reconfiguring Global Space: The Geography, Politics, and Ethics of Drone Warfare,” which took place Indiana University – Bloomington in July of this year

By Arthur Holland Michel

The drone, most often represented in some variation of the distinctive form of the Predator or Reaper, has elicited a more vibrant, fervent, frenzied, and confused cultural response than any new military technology since the nuclear bomb. The drone has been parodied, satirized, caricatured, excoriated, and fetishized in a wide variety of outlets and media, including late night talk shows, cartoons, Hollywood blockbusters, rock music, street art, gallery art, comedy shows, and the White House Correspondent’s dinner, among others. Why is this? What do these cultural responses look like? And how do they influence the public debate (and, by the same token, the eventual policy)?

Though earlier references to military drones in popular culture do exist, the period from 2010 to the present has seen the drone make appearances in popular culture at a far more frenetic pace than ever before. This is not to say that people weren’t already scared of, or fascinated by drones before 2010. Indeed, as far back as 2003, just two years after the U.S. first used armed drones, the drone demonstrated its potential to capture the public imagination: in the lead-up to the War in Iraq, George W. Bush’s administration told the world that it had evidence, which later proved to be false, that Iraq had its own fleet of drones capable of carrying WMDs several hundred kilometres. This announcement sparked a short but intense media frenzy. It was the technological sophistication that the drone evoked that motivated the public response to the U.S. government’s claim.

In 2003, armed U.S. drones had only been in operation for about 18 months, and the targeted killing campaign, which is perhaps the most controversial application of drone technology, was still in its infancy. Starting in 2009, there was a dramatic uptick in the use of armed drones outside of declared war zones. It has also arguably also seen a more dramatic shift in the public conversation around the issue than in the whole previous decade. As the drone becomes more prevalent in popular culture, its representations will continue to feed and influence the public conversation. While it is hard to draw a direct line between popular culture representations of the drone and shifts in public opinion, the audiences for these representations are orders of magnitude larger than other sources that might contribute to public sentiment on the issue, such as think tank reports and op-eds. Likewise, by summarizing and crystallizing popular feelings and assumptions about drones, these representations are a useful barometer for understanding how the public understands the drone, and what it thinks about it. Though popular culture representations certainly aren’t the primary source of the public’s perspective on this technology, they certainly serve to both illustrate and reinforce it.

In many instances, the drone’s novelty—its unfamiliarity—has served as basis enough for these representations. In 2012, the artist James Bridle drew a series of to-scale silhouettes of military drones on the streets of London and Istanbul (the installations were later reproduced in other cities, including Washington, D.C.). These Drone Shadows, as they were called, were picked up widely in mainstream news and media outlets. In an interview, Bridle told the Center for the Study of the Drone that the works are “about the absence of the drone in the contemporary discourse…a few years ago when I started making them no one was talking about these things. The project was just about how no one knows what these things even look like.” A common reaction among passers-by, according to Bridle, was disbelief at how large these aircraft are (a Predator’s wingspan is just shy of 49ft).

Indeed, few people have ever actually seen a Predator drone in person. One of the few Predators that is publicly viewable is Predator 3034, which is hanging in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. News outlets covering drones tend to recycle a small set of now-canonical stock photos—one of which, James Bridle discovered in 2013, was actually a CGI rendering. Meanwhile, millions of people have encountered drones in the popular media portrayals (John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight monologue about drones, in which he refers to a drone as “a flying death robot,” has been viewed about 6.8 million times on YouTube). These portrayals are therefore significant: in the period from 2010 until the present, when many people had heard about drones but few had had an opportunity to come face to face with one, even a small hobby model such as the DJI Phantom, high volume media outlets effectively held a monopoly on the public’s relationship with this technology. Any comprehensive analysis of the roles of drones in politics and society must not overlook the their treatment in popular culture.

During his speech at the 2010 White House Correspondents Dinner, President Obama said, “The Jonas Brothers are here; they’re out there somewhere. Sasha and Malia are huge fans. But boys, don’t get any ideas. I have two words for you, ‘predator drones.’ You will never see it coming.” In the days that followed, the joke was pilloried, given that Obama does indeed call drone strikes against his enemies in real life. Obama’s reference to the Predator drone is illustrative. You could imagine that if Obama had told the Jonas Brothers, “I have two words for you: Navy SEALS,” he might not have garnered the same laughs. Special Operations serve together with drones as the tip of the spear in the war on terror, but they don’t resonate with the public in the same way that drones do. Instead, the joke riffed on the prevailing understanding that the President could order drones upon anybody how drones work and what they are used for.

It also was one of the few times that Obama ever acknowledged his direct role in drone strikes. Precisely during this period, as Daniel Klaidman illustrates in Kill or Capture: The War on Terror and the Soul of the Obama Presidency, Obama was actively pushing the CIA’s targeted killing campaign, and is said to have personally ordered numerous strikes himself. In addition, in 2010 Obama and his legal teams were debating the legality of using a drone strike to target Anwar Al-Awlaki, who, like the Jonas Brothers, was a U.S. citizen. It is funny, in a way, when Obama threatens to call a drone strike on a boy band because he is one of the few people in the world who actually has the authority to actually call drone strikes. His statement that “you will never see it coming” refers to the prevailing impression—which is accurate—that a team operating a drone will see you long before you will see it. In his May 2013 speech at the National Defense University, Obama’s most extensive and detailed speech on the U.S. drone program, his tone was much less lighthearted. “For me,” he said, “and those in my chain of command, those deaths will haunt us as long as we live.”

In Amalie Flynn’s poem Drones, which was published on The New York Times blog At War that same year as the White House Correspondents Dinner, the narrator lies next to a drone pilot who is haunted, like Obama, by his actions. “In your sleep they fly above you,” she says, “Swarming your sky ready to strike.” As early as 2010, the idea that drone operations carry a high risk of PTSD—an idea which later studies cast doubt upon—was de rigueur in the public discussion. In 2013, Yahoo! News commissioned the poet Michael Robbins to write an inaugural poem for President Obama. The result, which the news site eventually opted not to publish, took aim, first and foremost, at the drone program: “This is for the drone-in-chief./ Mumbai used to be Bombay./ The bomb bay opens with a queef.” Robbins seemed to be suggesting that Obama’s most profound impact on the global stage is his drone campaign.

In 2013, the Nigerian-American writer and photographer Teju Cole wrote a series of tweets that modified the famous first lines of seven books so that they would be about drones. “Call me Ishmael. I was a young man of military age. I was immolated at my wedding. My parents are inconsolable,” he writes. The project proposed, or actualized, a culture in which the drone was inescapable—every story, every action not only occurs in the context of the drone; all life is dominated by it. Cole’s project seemed to argue that contemporary culture, likewise, cannot exist in isolation of what the United States is doing in its wars overseas—and those wars are encapsulated by the image of the drone. Among high-culture representations of drones and drone wars, Cole’s was one of the most widely republished.

2. Call me Ishmael. I was a young man of military age. I was immolated at my wedding. My parents are inconsolable.

— Teju Cole (@tejucole) January 14, 2013

Cole’s project resonated in part because it was one of the first to propose the stark implications of drones for culture; other projects have proposed the implications of drones for our everyday lives. One such representation might even be reasonably said to have been pivotal in the feedback loop between media and debate. In December of 2012, a group of artists and entrepreneurs created their own media frenzy when they unveiled the Burrito Bomber, a small unmanned aircraft that, according to their website, “flies to your location and releases the Burrito Delivery Tube. The burrito parachutes down to you, the drone flies itself home, and you enjoy your carne asada” [bolding in original]. Briefly, the burrito drone became a sensation—many didn’t realize that it was more a conceptual joke than a business plan. It gave many Americans their first taste of the potential benefits of domestic drone integration. Suddenly, people realized that drones could be used to deliver food instead of bombs (the Oxycontin Drone and the Poetry Drone played with this same idea, though in an even more conceptual and satirical language).

To this day, it is still common to hear people say, in speeches and presentations, “drones can even be used to deliver burritos!” By calling the drone the Burrito Bomber, the team cast the device in a light that would likely resonate with prevailing understandings of drones at the time—that is, as a tool for military use. The idea that a tool for war could just as easily be used as a tool for food delivery cemented the already commonplace practice of reappropriating the verbs of warfare—bombing, spying, snooping—to describe applications for drones (one headline from around the same time: “The NASA drone that spies on hurricanes”).

The appearance of the drone in comedy is particularly illustrative. Drones, a skit that appeared on the Kroll Show in February, 2013, imagines a squadron of drone pilots whose experience of warfare resembles an episode of The Office: the central character, a pilot, squabbles with colleagues over stolen donuts, has problems with his carpal tunnels, and struggles to convince his son that he is “a real pilot.” Executing a strike, it seems, is as simple as clicking Yes on a dialogue box on his screen that reads “Would you like to Drop a Bomb?” Like so many representations of drone warfare, the skit implies that drones are autonomous: “Hurry up, Doc,” the pilot tells a colleague who is out on a coffee run in the middle of a mission, “these drones aren’t going to fly themselves.”

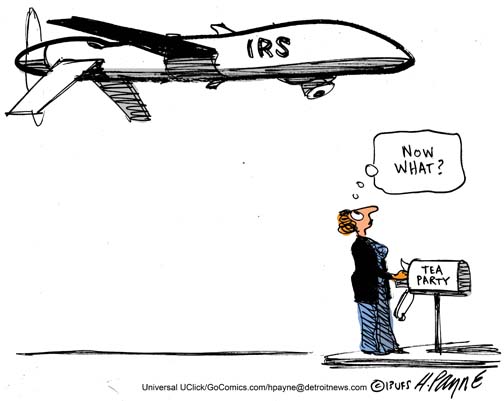

A brief and informal survey of political cartoons about drones indicates that a majority depict some variation on the Predator drone, engaged either in surveillance or a strike. Many emphasize the drone’s frightening, ominous potential. Even those cartoons that seem to reflect a hawkish stance still depict drones in this way: in a drawing by Sack that appeared in the Star Tribune, Uncle Sam—with an Predator drone perched on his hand—tells Pakistan, who has a vulture representing Al Qaeda on his, “We’ll curb our soulless killing machines when you curb yours.” Several cartoons imagine, bizarrely, the IRS flying Predator drones domestically.

The descriptors associated with the drone have, at this point, emerged with sufficient repetitiveness to be approximating the condition of trope: in the landscape of the portrayals discussed in this paper, drones are all-seeing, silent, lethal, and, quite often, autonomous. These descriptors have meant that depictions of drones in popular culture are often exaggerated, if not technically inaccurate. The idea of drones being autonomous is among the most often repeated of these tropes. Indeed, there is a heated international debate in progress over the legality and morality of the use of lethal autonomous weapons, also known as killer robots. Even though, as Paul Scharre and Michael Horowitz point out in their primer on autonomous weapons, highly autonomous killer robots do not yet exist, the temptation to depict today’s drones as free-thinking, autonomous machines has proven to be too strong. In a 2014 skit by the comedy duo Key & Peele, a character by the name of Luther, who is President Obama’s “anger translator,” gets excited about America’s lethal drones, declaring—to Obama’s dismay—”Y’all should be embracing this technology. Cos it’s pretty amazing, man. It’s awesome. All you do is pick up the phone and say, ‘Excuse me, I’d like to order two dead terrorists’…It’s amazing. I mean, we can murder people with flying robots!” Obama, clearly not comfortable with Luther’s characterization of the drone, loses his patience and orders a drone, which appears to be autonomous, to fly over Luther’s head ominously.

One of the more curious, and extreme, representations of the drone as a free-thinking entity was a 2012 Saturday Night Live sketch called Cool Drones, which portrayed a group of drones that form a boy band. It is unclear why exactly it would make sense that a group of drones, if left to their own devices, would elect to join forces and make pop music, but they do. Meanwhile, the Drunken Predator, a fictional Twitter personality with a foul mouth and a heavy conscience, has delighted followers with lines like “Roses are red/ Violets are blue/ My thermal camera/ Is locked on to you.” Audiences appear to be delighted by depictions of drones as intelligent robots, even though these depictions do not accurately reflect where the technology stands today.

This idea of the autonomous drone has also been deployed in more sinister depictions of drones. A short film called Our Drone Future, puts the viewer inside the perspective of a police drone that patrols San Francisco’s skies, deciding for itself where it wants to go, who it wants to track. The drone even disobeys the orders of its human supervisor.

Drones have made numerous appearances on the big screen. But no movie has dived deeper into the issue than Andrew Niccol’s Good Kill, in which a wizened Ethan Hawke plays Maj. Thomas Egan, a USAF F-16 pilot who has been relegated to an armed Predator/Reaper squadron based in Nevada (an assignment derisively referred to as “life at 1G”). Like the drone pilot in Grounded, which opened in spring, 2015 on Broadway starring Anne Hathaway, Egan dreams of flying a manned aircraft again. This desire to be physically airborne is the context for his psychological torment. Egan is tormented by the signature strikes and double-taps that the CIA orders him to take; he watches in horror as women and children die. He has a breakdown, but it’s unclear how much of that has to do with the killing, and how much of it is a result of missing the thrill and fear of flight.

The movie, which is laced with inaccuracies, confirms many of the assumptions that are the basis for the public controversy around drone strikes. It will one day serve as an important time-stamped portrait of the public drone debate in the period of 2013-2014. (It is also full of awkward exposition dialogue: characters explain the basics of drone operations, presumably because it is assumed that most viewers don’t have the remotest idea what “remote split operations are.”) While the film makes a sincere effort to insert some greyness into what is, in so many popular culture representations, depicted as a black and white issue, it lands firmly in the position that drone strikes are bad for the people at both ends of the satellite link. In Good Kill’s depiction, the CIA, depicted as a nameless voice that barks orders over a secure phone, is guilty of war crimes. The voice says that nobody takes civilian casualties more seriously than the CIA; this is, in the movie’s telling, eminently untrue.

The movie is particularly interesting because it reflexively portrays the public debate around drones that is, in turn, fed by representations like this movie. Egan’s commander, Lt. Col Johns, tells a group of drone pilots in-training that they are joining a controversial program. “We get a lot of shit from the public. And I’ve heard all the bleeding heart arguments. I’ve read all the fucking bumper stickers: ‘It’s not the Air Force, it’s the chair force.’ ‘We’re waging a Wii war.’ It’s all a waste of breath. Because the United States Air Force is ordering more drones than jets. Excuse me—Remotely Piloted Aircraft. You can call them whatever you want.” At the end of the day, the movie declares, mostly through Col. Johns, the public and the drone operators can debate all they want, but it won’t make any difference. Drones are here to stay, drone pilots will continue to be troubled, and policymakers are indifferent to the claims and needs of either the pilots or the public. Later in the movie, after a particularly deadly strike, Vera Suarez, Egan’s sensor operator asks Lt. Col Johns, “Was that a war crime, sir?” He tells her to “shut the fuck up.”

And yet there is also ample evidence to suggest that the public debate does influence policy around drones, and that popular media portrayals inform the public debate. In a statement to the United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, the U.S. delegation wrote, “‘lethal autonomous weapons systems’ appears still to evoke the idea of a humanoid machine independently selecting targets for engagement and operating in a dynamic and complex urban environment.” The delegation was fighting against what it understood to be a common public perception of this technology based more on the Terminator movies than on facts.

The drone industry has also recognized the effect that media portrayals, especially negative ones, have on its bottom line. In the years since drones became a fixture in popular culture, the unmanned aerial systems industry fought hard to convince the public to banish the word “drone” from its vocabulary. The word ‘drone,’ industry representatives have argued, evokes an image of an autonomous, killing machine: the language that Toscano and others used to describe what they consider to be “inaccurate” portraits of unmanned technology closely matches the language that these popular culture portrayals use to describe drones. Toscano has even explicitly indicated that the these negative connotations have their origin in popular culture: “I don’t use the word drone,” he said in an interview with the National Journal. “There’s a Hollywood expectation of what a drone is. Most of it is military; most of it is very fearful, hostile.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vcV71liAMwc

Even though hundreds of thousands of Americans now own hobby drones, the idea of the drone as an autonomous killing machine still persists. It appears to be less common for members of the public to equate military and civilian unmanned aircraft, and yet we are generally still receptive to portrayals of drones that do exactly that. An Audi commercial from earlier this year exemplified the kind of hyperbolic representations of the drone that the industry worries about. The ad took aim at the concept of drone deliveries (DHL, a German company, has conducted limited drone delivery tests). The fleet of package-carrying quadcopters, for no apparent reason, turns violent. The commercial transforms into a scene straight out of Hitchcock’s The Birds. Somehow, it does not feel unnatural to posit a scenario in which a fleet of delivery drones would start killing humans.

As drones become more common in everyday life, we will see the popular culture response to the technology become less frenzied and more nuanced. It will no longer be funny to equate Amazon drones with Predator drones. Depictions of lethal delivery drones, such as those seen in the Audi commercial, will no longer resonate. But in the meantime, as society continues to come to terms with this technology, and we work to wrap our heads around its implications, popular culture portrayals will play a pivotal role in the way we talk and think about drones.

For updates, news, and commentary, follow us on Twitter.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]