High & Low Bureau is a curatorial duo comprised of Yael Messer and Gilad Reich. Their work explores how power, technology, and activism interact in the 21st Century. Their latest show, Decolonized Skies, explores the ways in which artists and activists have worked to reappropriate the aerial view from the surveillance state. The view from above, they explain, “is traditionally a view of power, of state power, of corporate power, a view we were educated to think of as a perspective of control, of obedience.” The show, which will be up at Apex Art in New York City until October 26, brings together works and projects in multiple mediums, spanning over a century.

The following interview is based on a public conversation between High & Low Bureau and Arthur Holland Michel that took place on September 16, 2014 at Apex Art in Lower Manhattan.

Arthur Holland Michel When I was on my way down here, on my way to the show, and wondering what I was going to talk about, there were two news helicopters, hovering dead still in the sky above Washington Square. Obviously something had happened on the ground. And it made me think. These news organizations are willing to invest a huge amount of money just to get a view from above. To me, this gives a pretty good indication of the appetite we have for the view from above.

We’re seeing more government and military drone use than ever before. But we’re also seeing more civilian use, and use by artists, and use by researchers. And that creates an interesting dynamic, and interesting matrix, that we want to explore a little bit tonight. Sound good?

Yael Messer and Gilad Reich Yes.

Holland Michel What was the origin of “Decolonized Skies”?

Messer Our projects always deal with an intersection between a social-political issue and artistic practice, that is, meeting artists and develop projects with them. There are these issues that we are concerned with, and we see them as having an urgency, that we’d like to develop further. And so we think about how to bring those practices together as an exhibition, as a will in itself.

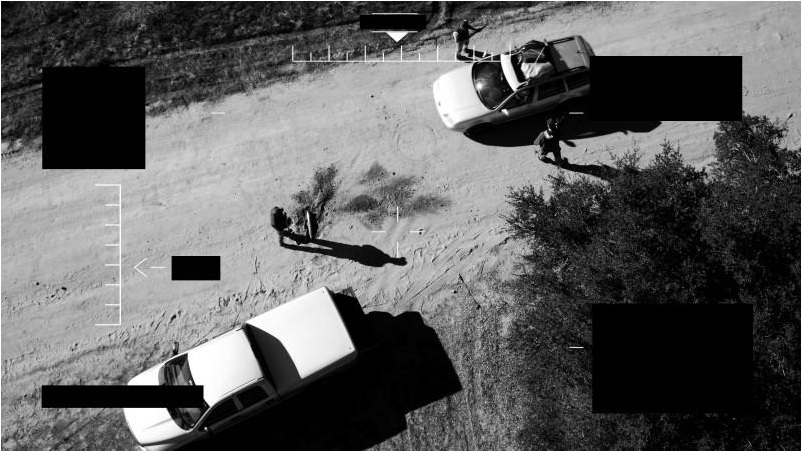

Reich We were in Istanbul, in Turkey, for the Istanbul Biennale, and we happened to be there during the civil uprising, the demonstrations, which was very inspiring. Among other things, we saw a protester using drones against the police, trying to map the power relations in the open space, and also to document police violence. It was also around this time when you could see in the news, images like this, from Egypt, part of the civil uprising:

You can see the view from above, which is traditionally a view of power, of state power, of corporate power, a view we were educated to think of as a perspective of control, of obedience, is now suddenly being re-appropriated by activists for different reasons. It was very inspiring for us. It was also around that time when George Clooney came out with his project, where he bought, or partially bought, a satellite that would watch over Sudan to document the situation. This is a very problematic project for many different reasons, but still, it’s interesting that someone can take this kind of initiative.

Messer Yes, it actually all started with George Clooney, and my admiration of George Clooney, and then, you know, we thought to do a project about it.

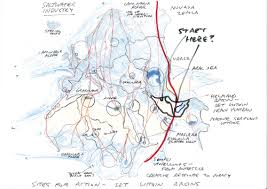

Messer Here’s an image by Jananne Al-Ani, who during 2011 constructed satellite images in Iraq, suggesting kind of an alternative reading:

And here is a shot from Omer Fast’s “Five Thousand Feet is the Best,” a beautiful video that is, as is usually the case in his works, kind of between a fiction and reality, where the main character is actually a drone pilot.

Reich There is all this drone talk around how the U.S. is using drones in Afghanistan, and in Pakistan, and in many other places, and how Israelis, and the Israeli government, are using drones in Gaza and in many other places. Here is the CEO of Israel Aerospace Industries selling drones in Singapore, to different governments. This fellow is very proud of it.

While the artistic side is happening, the activist side is also in urgent response to what is happening right now in the world, this massive use of drones for the purpose of destruction, of attacks, of surveillance. Everything came together in the point that we thought it was interesting to take this moment and bring different instincts together for a project that looked at civilian perspectives of drones, of artists who are committed to the production of civil knowledge rather than a military perspective.

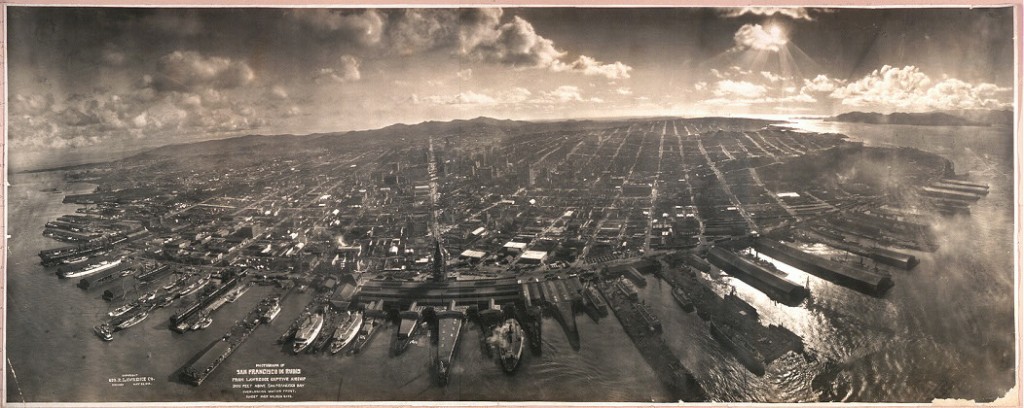

Holland Michel Despite the fact that it is such a pertinent, of-the-moment issue we have here, in the exhibition, an image from 1906. It was taken by George Lawrence, using a camera attached to a series of kites. That is San Francisco after the devastating earthquake that happened that year.

This is over a hundred years old. Why do you feel that in order to explore very contemporary issues, you thought it was important to bring this historical perspective into the picture?

Messer I think it also relates, again, to our working process. Because we deal with current, urgent issues that, again, we see within the practice of art, or architecture, or of thinkers, part of the research is to look at different kinds of references. And so usually we tend to show works that were considered to be in the past, considered to be historical, as a way to contextualize the issues. As a way to make them more present in this current time. We also looked at history, because this issue that we’re talking about has a genealogy. There is a history to it. Now there is a huge tendency, with the drone art and with aerial photography, but it has some kind of root. The perfect submission, sometimes, is to bring different practices, different perspectives, to one element. There is always at least one anchor, if not more—

Reich A historical anchor, in a way—

Messer —to contextualize, from a different perspective.

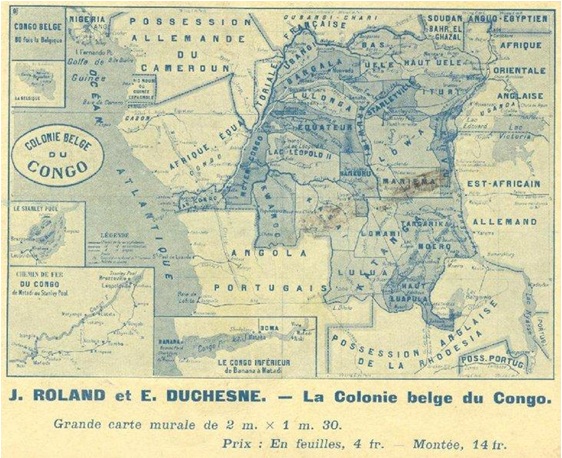

Reich Always, when you start to research about something—especially if it’s historical research—you find out so many things you had no idea about. So, for us we saw that the view from above, like I mentioned before, was always militarized, was always a view of power. Here are few almost random images of the view from above as a tool for map-making in the colonial age.

Then it was re-appropriated by the military in very creative ways.

Holland Michel This is the pigeon drone, right?

Holland Michel This is the pigeon drone, right?

Reich Right, exactly.

Holland Michel The cat chases the pigeon drone, obviously. That’s how it all works.

Reich When Nadar, the French photographer, took the first aerial photo above Paris, he published the photo, and then the French army asked him to take photos for them. So actually, you realize that the view from above, or aerial photography, it starts with pioneers in photography who wanted to explore, of course, photography, but also to expand our vision. It leads to questions of citizenship, of obedience, and of disobedience. Before it was appropriated by the state, it was civil property. For us, it was very interesting to contextualize this photo, for instance, as a civil practice, as a comment on a tragedy that had just happened, and as far as we know, that helped the local community to understand what the situation was and how they can react. So, of course, only later the military came in. We realized there is almost a hidden history of civilian-oriented use of the drone.

Holland Michel As soon as we got airborne, we were trying to figure out ways to capture images from the air. It happened simultaneously. There was no lag period. And also, as soon as we were capturing images from the air, the military was trying to figure out how they could make use of this technology.

In the last few years, we’ve been seeing a burgeoning of aerial art, and a lot of the art we see in this exhibition has a political or activist bent to it. But we’re also seeing art that is non-political, that is just beautiful, or is an attempt at beauty. Do you, as curators, as observers of art, consider the view from above to be a thing of beauty? And how do you think that beauty operates in the dynamic of the work that you’re looking at?

Messer I think you’re referring to both paintings and photographs, that is a genre in and of itself. In aerial painting and aerial photography, the point of view from above is the point of departure for the practice, and it’s definitely a genre in itself. I think it is a bit different from what we are trying to do, because we’re interested in this idea between the aesthetics and the ethics. If we think about George Lawrence, or aerial photographers today, which realm are they working in? The aesthetic or the ethical? We’re interested in where the aerial view took on an even more practical use.

“We are looking at the notion of civil responsibility, and the space where ethics come into the frame.I will say that we’re not interested in the aesthetics per se.”

Reich So there is the aesthetic field, and there is the practical field. As you know, there was a beer delivery service with drones, briefly. And there is Amazon. What we are looking at is the intersection between all these things, and the notion of civil responsibility, and the space where ethics come into the frame. I will say that we’re not interested in the aesthetics per se.

Holland Michel That being said, there is an allure to even the images we see up here. Do you think, having spent this much time researching aerial images, you could make an educated guess as to why we find a view from above appealing?

Reich Well, of course there is something appealing about it. This sense of control, this sense of perspective. Sometimes it helps us to situate ourselves, and in that sense the view from above has a lot of power. And in a way we are educated to look at these images like that, because we are educated that the view from above always comes from a position of power. In a way, what we’re trying to do with this exhibition—what the artists are trying to do—is to deconstruct this power. They do it in various ways, and what’s interesting is that they’re trying to bring the personal and the humanistic element into the use of the view from above, and in doing so, deconstruct it—except for George Lawrence, which is a bit of a different case.

For example, there is the video here in the show, Vanishing Vanishing-Point, by Effi & Amir, which is very personal, very poetic film essay, where they use Google Earth and Google Street View.

But also, for example Peter Fend, whose Ocean Earth work is posted here. It is more of a journalistic world, with facts, and with scientists, an attempt to track ecological disaster throughout the earth.

By using handwriting, he breaks hold of the rational, objective element, which is what’s so tempting about the view from above, and which is also related to this powerful position. In the work of Bik Van der Pol, they use satellite imaging, but they also talk to people in the neighborhood, and they record the conversation, and you can hear this conversation. So all these artists are putting a personal element, a human element, into their practices, and this is to deconstruct this power position.

Holland Michel How do you see this power operating as more of the aerial view is reappropriated from the government, from surveillance powers? When it becomes democratized and common fare, what happens to the power at that point? How does that change the equation, in terms of considering the view from above?

Reich I would say first that we have to question the notion of democratization. Of course there is this distribution—this re-distribution of the view from above—but as we’ll learn from the forensic architecture project, it’s still a very privileged position, to be able, not only to get the view from above, but also to analyze that, because, as I mentioned briefly before, to read aerial photos you have to be educated. There is something very tricky about these images. It seems very objective and easy, but actually you need a framework to read them. And if you read, for example, testimonies from drone pilots, they always will tell you that what they see is very blurry even though it is very advanced technology. And they make decisions based on many other aspects, for instance, like, suspicious behavior, this kind of thing. There is something very tricky. It is like the double disguise of the view from above. So we have to be very careful about what we mean by the term “democratization.” In the Forensic Architecture project we see that you don’t get to choose to be hit by a drone. The only force you have is to analyze, doing this forensic investigation after the attack. But the number of people who can control this power is very limited. And even now, with the whole drone “mania”, it’s a very tricky thing.

But of course, as it happens, there are more and more uses of the aerial perspective, and all the projects in the exhibition also have this practical element in them. How can artists re-appropriate this perspective in different ways?

Messer We’ve got to think in terms of the future. Think, for instance, about what you’re doing at the Center. I think there is more awareness, and I think this is what we’re talking about. It is about shared knowledge, and expanding this knowledge, as we don’t know a lot of information. I think more and more, it will be difficult to do what we are doing here, and I think, in a way, this is the optimistic view. There is a way for the future, whatever that means, that we will expand and it will be by the shared, common knowledge of what we are doing.

“Think of the photographers, geographers, urban planners, scientists, and designers that are involved in the aerial view. This is a promising thing that we can know something about these images today, and that this process of democratization will force us to work together.”

Reich Which brings us to the point of all the projects in the exhibition, that they are collaborative projects. So there is something about the process of analyzing these images that demands, or asks, for collaboration between people from different fields. Think of the photographers, geographers, urban planners, scientists, and designers that are involved in the aerial view. This is a promising thing that we can know something about these images today, and that this process of democratization will force us to work together.

Holland Michel The University of Leicester, came up with this project to crowd-source search and rescue operations. If a person was lost in an area, they would send a drone up and take photos of the whole area. They would then put those photos online, and people would almost treat it like a game, scanning through these photos until they found the lost person, who was probably just sunbathing, or whatever the case may be. This is an example of people taking that view and analyzing it collectively, as you say. There is a lot of data to analyze, so it’s a real question of making sure you can get through that, but it’s also about engendering the spirit of collaboration, because the aerial view really does give you a sense of how small we are, and how big it is.

But there is flipside to that point. There is a romance with the aerial view, as being a bit of a panacea. As the U.S. is looking to embark on yet another campaign against one of the country’s enemies, I think of how Stanley McChrystal, the U.S. general, said that “the drones don’t give you the whole picture.” In the artistic context, that suggests that there is a certain abstraction that you get when you have the view from above. We as humans experience the world naturally from ground level. Do you get the sense that the aerial view is perhaps more abstracted than we would like to believe? That there is perhaps less useful information in there than the visual impact of the image might promise?

Reich This was one of the most surprising thing about this research, which I referred to in my last answer. We were educated to believe that these images are objective, are natural in a way, but they are totally not, for different reasons. First, you have to learn the context in which to learn them. Then, for example, in the military use, when you take photos from above, you have to tie them together in order to make a whole, because you get these small parts, so this is another skill that you have to learn, and usually you learn it in a military context. The most interesting element, almost, is that most of the images we see, also in Google Earth, and other more democratic or open sources, are already either censored or manipulated. Because Google has all these agreements with all the countries. For example, you can only really see about half of Israel. The rest is blurry. You think, “hmm, it’s a bit blurry because it’s taken high from above.” But no, it’s blurry because someone asked Google to blur the image. So you never know what is going on, if it’s just blurry because of the quality of the image, or because there is something going on there, or because someone tried to hide something from you.

The work of Bik Van der Pol is very interesting here because it plays with this gap between what you think you see and what you actually see. For the project, they created this very large text piece in parking lot, so you cannot read the text while you are standing there at ground level. You must have the view from above, and they cooperated with Google and took this image:

You think, “it worked!” But actually, what we discovered while working with them on this project is that they were manipulating the image provided to them by Google because they couldn’t see anything in the original. So they completely photoshopped the image, and the image that they present, to represent the project in the end, is a completely manipulated image.

This has to do with the question of truth, which is also the question of power, and what is the power of those images. Because there seems to be this objective quality to the images—you believe them, or you want to believe the image—but it is more complicated than that. For example, Peter Fend had a strong belief in truth and the truth that these images deliver if you read them correctly, if you have the right people to read them. But if you talk with Effi & Amir, or with the people from Forensic Architecture, they will tell you that it is the other way around; no, these images are manipulated, are pixelated, in order to hide certain things.

Messer Abstraction is a language that artists use. It’s not something foreign, and it’s not something that they are afraid of. Effi & Amir created a whole fictional story based on what’s considered to be truth, and what’s considered to be abstract. Through the art they’re answering that question beautifully, because it is about how we can use abstraction.

Holland Michel In satellite images, they manipulate the colors to make it look how we imagine that the view from space actually looks. They are just catering to our sense of what we should look like from space.

One of my favorite instances of reappropriating surveillance is by an artist named Jeff Guest who used a speeding camera in Australia in 1993 to take his wedding photo.

It was memorable, but it also had a practical value: they got something practical out of a technology that was not intended for the benefit of wedding parties. Are there some examples of other practical uses of the view from above that you found compelling that you weren’t able to fit in the space?

Reich There is the Grassroots Mapping project, which helps local communities create DIY aerial maps using balloons. It’s a participatory project where all the people of the community learn together how to take the photos how to use the cameras and how to analyze the photos. This is a very empowering project for different communities. The Israeli branch of Grassroots Mapping did a project for the Palestinian community in East Jerusalem. If they had tried to take a photo from a drone, they would have been by the police. So with the balloons, this was the first time they had an overview of where they live. They could see the power relations in the space, and they could track the future plans of the authorities. If a few kilometers away someone is going to do something that will influence your life but you have no idea that it’s going to happen, this system can really help.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]