Anab Jain is the cofounder of Superflux Lab, a design practice based in Ahmedabad and London. Its projects examine the ways emerging technologies integrate with our environment and everyday life, exploring these implications in a multidisciplinary fashion. By combining art, research, and development, Jain is creating new ways by which we interact and think about emerging technology. Her work on drones emerges from a long-held interest in the countless ways in which the technologies of the future will change our lived experience.

Superflux, which Jain founded with Jon Ardern, has produced “Mangala For All,” an ethnographic project on the streets of Ahmedabad that depicts the relationship between Indian people and the country’s emerging space program.

Superflux’s most recent project, ‘Drone Aviary,’ explores the impact of private drones within our public realm and how they will affect our urban experience. The film is a traveling exhibition, currently being screened as a part of the Civic Objects Display at the V&A Museum’s ‘All of this Belongs to You’ exhibition in London.

A filmmaker by trade, Jain won the Michael Moore Award for Best Documentary at the 42nd Ann Arbor International Film Festival for her film ‘Journeys,’ and has been honored as a TED Fellow.

We caught up with Jain to discuss her work with Superflux’s ‘Drone Aviary’ and the implications of living with drones in the ‘smart cities’ of the future—as well as the possible maliciousness of Indian aunties with their own personal spy-drones.

Interview by Tekendra Parmar

Center for the Study of the Drone Could you tell us about how you got interested in drones? How Superflux became interested in imagining a future with drones?

Anab Jain We were awarded a grant by the Arts Council of England to explore drones. We have always been interested in technology as such, and we are interested in the autonomous aspect of drones—how so-called ‘smart cities’ will live with such autonomous machines—and what it might mean for us live among these quite pervasive creatures, machines, whatever you want to call them. The drone is a representation of a wider interest in thinking about how we might live with such technology in the near future. The project is set quite in the near future.

Drone You said something interesting in your PopTech talk. You said, in reference to India, “Young designers need to be aware of the context in which they are working, the economically fragile recently independent state,” How do you see Superflux incorporating this intercultural standpoint within their creations?

Jain We’ve been asked that a few times. I don’t think that we can draw a straight line and say, “this is our Indian influence and this is our Western influence.” I think its just in our world view and our sensibilities, and our sensitivity to culturally present work that is not just Western—white—whatever you want to call it—our work is not necessarily saying, “this is a part of India and this is a part of the West.” This being said, I think some of our research and the ethnographic aspects of our work here reflect how I use to make documentary films in India. I’ve brought some of those methods of working with people and communities into our work here. I think there are more subtle influences, but it is a sense of cross-country brought into our work.

Drone Can you talk about ‘Drone Aviary;’ can you describe the project for us a little bit? And how the project came to fruition?

Jain The ‘Drone Aviary’ project was initially commissioned by the Arts Council of England to realize an installation for the London Design Festival in September last year. The project’s premise was still the same—thinking about investigating the socio-political and cultural significance of drone technology as it enters the civic space, and what it might mean to live with it.

For that particular installation we were going to have a series of flying drones for about a week, and people would get a chance to—not necessarily interact—but be in the presence of these drones. There was going to be a series of films and video feeds that would show the world from the drones’ points of view. The idea was that the film starts revealing the view of the city and the data these drones attempt to log. Primarily our interest is in thinking about these drones as data acquisition devices, as devices that have certain amount of autonomy and agency, and seeing how they might make decisions and how they may impact our lives.

That was our project, unfortunately it fell through, but we developed it so far that we didn’t want to stop at that point. We’ve been invited by different places to show extensions of the same project, its an ongoing R&D project in this sense. We’ve made a new film for the V&A and added two more drones to it; we’ve flown a few of our drones outdoors. We’re just going to see what happens next.

Drone The V&A exhibit, what you were working on today, can you tell us a little bit about that?

Jain Sure. Basically in the V&A, we are part of this exhibition called ‘All of this Belongs to You’ that opens today (April 1st), and the exhibition is basically saying, at a time when we are going to have an election— the UK is going to engage in a democratic process—how can this exhibition, ‘All of this Belongs to You,’ ask how a museum can be a public space? How it can explore the wider role of public institutions in contemporary life?

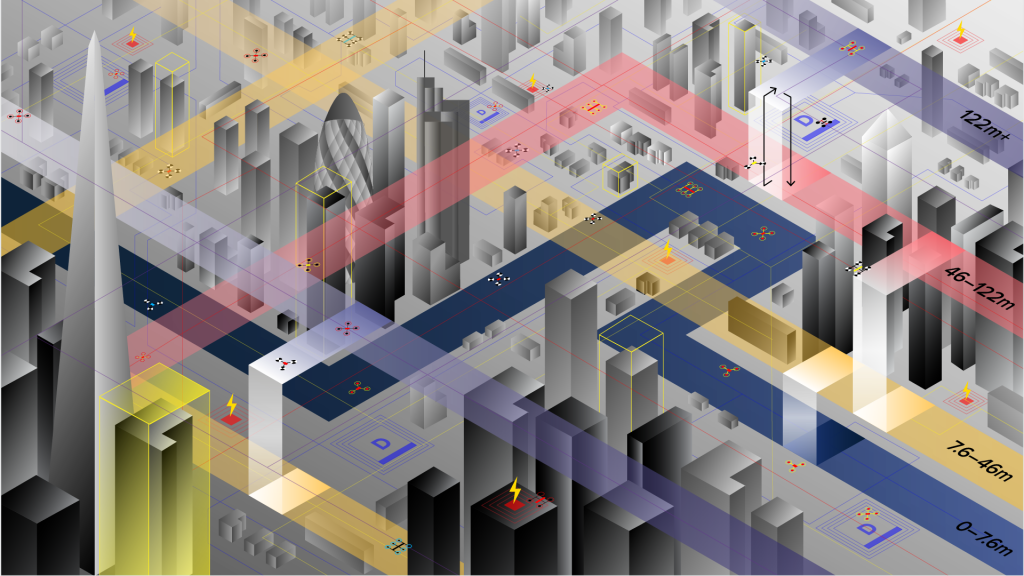

Our project is a part of the ‘Civic Objects’ display. The idea is that, I think our intent is to raise questions about who owns airspace and what is a civic space when it comes to airspace. What are the infrastructural frameworks and networks that will need to be created for these drones to fly in cities?

Drone Can we talk about that a little bit, how does ‘Drone Aviary’ imagine those infrastructures to be, what do you see those infrastructures to be that will allow cities to become smart cities in the near future?

Jain We briefly touched on the infrastructural aspect; as for the previous project, we were going to build an aviary of sorts. We were going to try and have these perches, landing stations, and charging stations, retrofitted within the city to show how a drone network may operate.

In this instance there is a map that is embedded in the film to describe these networks. And I think a part of the film starts to show a sense of geofencing that we might need to have.

We are interested in how as the network becomes physical, as each drone becomes a node in the network, and suddenly the invisible network starts to become visible through these flying machines.

Unlike buildings and roads and bridges, you’re talking about no-fly zones, geofencing, and charging stations, none of which will actually be visible. But it;s this sort of vertical geography, how do you dig into that, how do you design it, what is its relationship to the rest of our built environment. There are so many unanswered questions about this technology.

Drone In ‘Drone Aviary,’ you see the city through the eyes of five different protagonists, the Nightwatchman, Madison, RouteHawk, Newsbreaker, and the FlyCam. Could you talk about these protagonists a little bit?

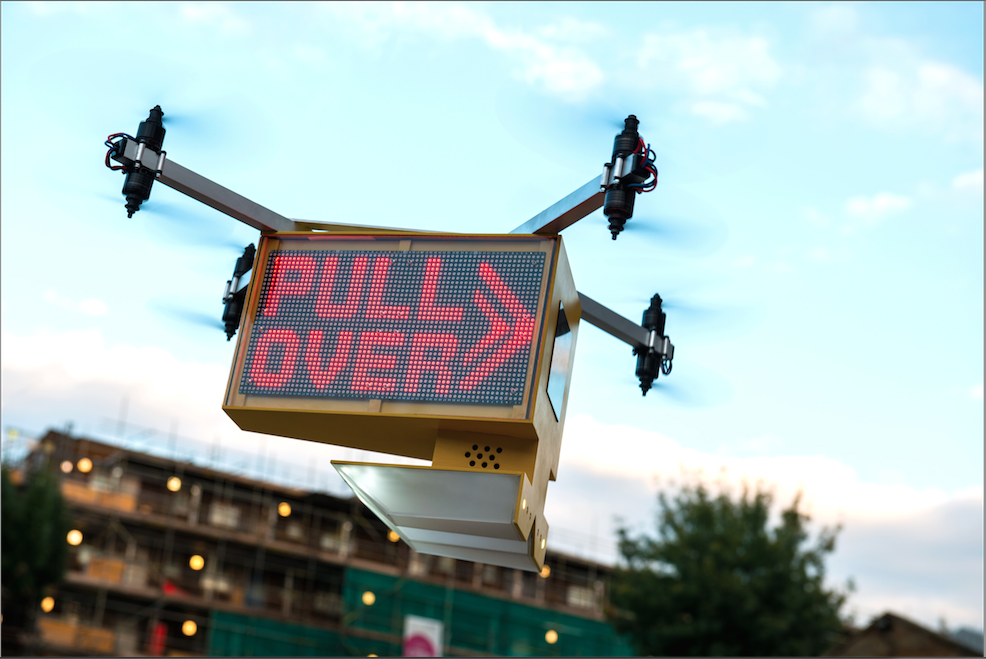

Jain So there are five drones, and each of these drones is designed to embody specific tasks and functions that are already gaining popularity. We are not trying to imagine new roles for drones; we are trying to build them as consumer products. The aesthetic we’ve chosen is not a hacked DIY aesthetic, but instead a carefully designed consumer product aesthetic.

Madison, the flying billboard or the advertising drone, is a hovering display platform; it uses sophisticated facial recognition to cater advertising to the interests of those that it’s around. And companies could probably hire it, and have it beam its advertisements out to people, by farming all potential data from all these potential consumers.

Drone You see that with a lot of these drones—farming data as such—even the Nightwatchman is cataloging data.

Jain Yes, we do think that every drone will be embedded with a certain amount of sensors. What those sensors do, and how much autonomy they bring to the drone, is the question. We are not suggesting that every drone is a surveillance drone. But they are surveillance drones in the sense of something that is constantly logging and tracking, doing quite mundane data logging tasks. None of this film or the ideas of it are special or unique, but it situates what we already sense and feel and makes it tangible.

Drone In a previous talk, you discussed a concept called jugaad—or guerrilla-design — What impact do you see jugaadi drones having in the smart cities of the future? Where would they play in with Nightwatchman, Madison, or the FlyCam?

Jain It’s not even a question that there will be the likes of GPS jamming or jugaadi hackers doing what they want to do with drones. For combatting it, we might have various countemeasures for drones coming from this hacker community. DJI Phantom enforced a firmware update to its products by which nobody can fly in Washington anymore. How are they going to enforce that with people that build their own drones?

We never did anything that was illegal.

Drone This goes back to the question about the ownership of airspace—Jugaadi or DIY drones may pose a certain threat—but it brings up the question, Who owns our airspace?

Jain Exactly—There are rules. And they are making the rules stricter and stricter. There are fuzzy boundaries. Nobody quite knows. Even today we don’t know where you can and can’t fly within a city. The film was filmed with drones flying around—and its fuzzy boundaries that can’t keep up with what’s going on.

There’s a fervor and excitement with huge amounts of investment and huge amounts of venture capital that go into funding drones now, which is completely disproportionate to the reality of what is possible. For us it was so important to build, and test, and fly. It’s so damn difficult to have something lift off the ground and fly into the sky, and stay there. It’s terrifying.

Drone Did you have any problems with regulations when filming ‘Drone Aviary’?

Jain We had a drone that was taking some of the overview shots. We never did anything that was illegal.

Drone Where is the line of legality within these situations though?

Jain That is the question. If you think about it… I know one guy, the BlackSheep guy [Raphael Pirker]. He filmed the Big Ben and the House of Parliament—and they’re trying to chase him down….

So many people are trying to fly drones now. It’s surprising. People will come and watch us in the park when we are doing tests, but they’ll also just pass by and say, “oh look…there’s another drone.”

Once it moves from the realm of excitement to being that sort of mundane thing that doesn’t matter anymore, that’s when it starts getting interesting. That’s when you can ask, what are the implications of living with drones? That’s what we’re trying to address.

Drone Do you think these drones that you have imagined will function differently in the East and the West—or the reaction to these drones will be different? Or do you see the difference as more superficial, lets say instead of the Nightwatchman in Ahmedabad you have the Chowkidar drone?

Jain I’m not sure about that. In India we have so much social policing. So maybe not the Chowkidar, but we’ll have the neighbor’s drone. You know what I mean? It’s not so much the Chowkidar, but rather my neighbor telling my mom that there were four boys visiting me today.

Drone So she’ll have the FlyCam patrolling your house—

Jain Possibly, ay?

Drone In ‘Drone Aviary,’ a voice states, “There are no programs of mass-surveillance and there is no surveillance state,” when everything is constantly being surveilled in the film.

You bring up the question of privacy in the film. Where do you see this question of privacy and drones heading? Do you think in the smart city privacy will disappear in lieu of convenient or targeted advertising, or is there something akin to Adblock for the real world?

Jain That’s exactly what we tried to capture. There is one shot in the advertising scene. The advertising drone is flying around a girl and she becomes pixelated, and it says access denied. Basically, that’s Adblock for the physical world.

One idea is that we’re going to have to pay a huge price for your privacy or retaining your privacy. You might have a service that says, “No-Ads.” You might pay 100 pounds a month so that you don’t get watched by Madison or don’t get targeted with ads. Its like there is no opt-in; there is only opt-out—and an expensive opt-out at that.

We want to talk about privacy, but we don’t want to say “yes” to privacy or “no” to privacy.

Drone There were also people whose responses to the advertisements were positive. There is a flipside to that. Where would you place yourself, would you be responding positively to this type of surveillance or would you want that anonymity?

Jain I don’t think its one or the other. At times you want it and at times you don’t. It depends what’s at stake. You know, on Facebook I want to keep in touch with my extended family, but I don’t necessarily want to share my kid’s photos on Facebook. I want to say, its not one or the other—whether I want to be fully private or whether I want to share everything, it just changes depending on the context.

We want to talk about privacy, but we don’t want to say “yes” to privacy or “no” to privacy. We just want to say that it’s more complicated than that. And we as human beings are going to have to make decisions and choices every time. It’s not easy, because you want to be online but you may not want to share. But then everybody is sharing, so you want to share—at least, that’s how my online experience behavior is: I think privacy in its pure sense…I don’t think that sort of thing exists. I think it’s the sense of choice that we have, the decision, the agency that we can exercise with what we want to do with our own faces and our own data.

Drone Right. You say at one point, “You think you are a consumer, but maybe you have been consumed.”

Jain Yeah. Like the FlyCam, is basically going to cost you nothing. But what you sign up to is the cloud. If you don’t pay for it, you are the product.

Drone Right. It’s like Facebook. You’re the product. You’re being sold.

Jain Exactly—you’re like a little pig in a big farm, waiting until they make you into sausages and eat you up.

Drone Well that’s a thought. Lets go from sausages and farming to nature. You talk about Bruce Sterling’s Next Nature in your Ted Conversation. Can you talk about Next Nature and explain that concept? And whether ‘Next Nature’ influences ‘Drone Aviary’?

Jain Maybe there is a loose connection, but it’s not really the focus of our work in terms of this project. Next Nature is basically a publication and a media project. But the essay that Bruce Sterling wrote about defining nature. The idea being, what is nature? We have this sort of nostalgic idea of nature, which is actually, in a sense, branded. And that’s what he’s trying to say, you know, “we’re trying to fight against GM crops,” but we’re still eating bananas, which have been modified over the number of years.

I think our work and our thinking is precisely in that state—this is complicated and this is messy—and don’t just have this nostalgic idea of nature as a clean and beautiful landscape where everything is fine, because that is simply branding.

Even as hunter-gatherers we were pretty much destroying nature. I think our interest is to show a glimpse of the same complication. And of course it’s a political position, but at the same time we do hope it gives enough opportunity for the viewer to reflect upon this.

Drone You ask in your Design for an Anxious Time talk, “What happens when machine intelligence finds a body and begins to occupy the sky above our heads?”

Can you talk about how the project addresses that question and contemplates how machine intelligence will change our lived experience a little more?

Jain Insomuch as the film in itself starts to hint at that agency very briefly. We don’t want to portray a science fiction world in which these machines are doing everything. We want to reveal some of the bugginess of the software and the fragility of these machines.

Drone You also ask this sort of esoteric question, the film quotes McKenzie Wark, “we no longer have roots. We have aerials. We no longer have origins. We have terminals.” and continues to quote Benjamin Wallace Wells, “In some real but imperfect ways, we exist in more than one place at once” this is also an aspect of that machine intelligence changing our lived experience, right?

Jain Absolutely, it’s disembodied. It’s that idea that you have a controller in your hand and it lifts you off your feet, and you’re pushed into this other world. Three-dimensional space compresses as a part of you is flying off—it’s a disembodied prosthetic of some sorts.

I haven’t fully read Donna Haraway’s work, but she talks about optics that bring with it its own politics. Drones are an optic moving through space. The idea that you are here, but you are also somewhere else. In one instance you’re inside a house, in the other instance you’re not. It’s the overview effect.

You know, it’s like the first time you see the pale blue dot. The first time you saw the earth through space. There is a sense of awe: the “oh my god, we live here, on this tiny blue dot.” That’s what they call the overview effect, which has changed our cognitive ability. Of course, people like Chris Anderson, founder of DIY Drones, say that by making everybody have drones and build drones, they are democratizing this overview effect, more and more people can experience this shift in cognitive abilities by being on the ground and at the same time above the ground. It’s fascinating.

Drone At the end of the film, I felt as though you were describing a world caught between two poles—a restless idealism on one hand and a sense of impending doom on the other—what do you think should be the feeling one should get from the ‘Drone Aviary’ installation? Or what do you think our final takeaway should be?

Jain It’s difficult to say one thing. But I suppose it is a chance for people to walk away, and the next time they hear about drones, smart cities, autonomous machines, or digital services—whatever—they perhaps think a bit more about how these things are actually situated in the world, and how they might be a part of it.

I think it’s making some of these invisible things visible. You see a billboard and you’re walking past it, but you have no idea that at that point this billboard is doing facial recognition and logging your data and changing its advertisement to suite your gaze.

I’m hoping for instance that if you see the film a few times, that you may start thinking, “this is what happens when things are invisible to me.” Each time you see a drone flying, remember it will have a sensor. Something is going to be collected.

For updates, news, and commentary, follow us on Twitter.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]