By Dan Gettinger

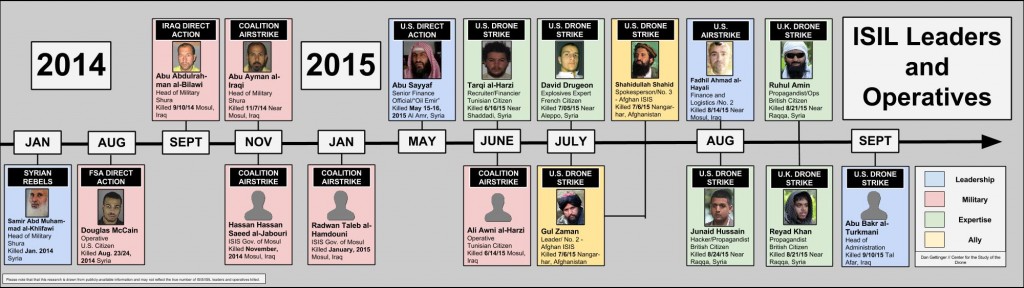

On August 21, 2015, Reyaad Khan and Ruhul Amin, two British citizens who had traveled to Syria to fight with ISIL, were killed in a British drone strike while traveling in a vehicle outside of Raqqa, Syria. According to the British government, the strike was necessary to prevent a domestic terrorist attack. “There was a terrorist directing murder on our streets and no other means to stop him,” Prime Minister David Cameron said in an address to Parliament on September 7. Although the United Kingdom has been carrying out airstrikes against ISIL in Iraq since October 2014, the strike that killed Khan and Amin was the first launched by the U.K. in Syria and as yet the only time that British citizens have been targeted using drones by their government. Shortly after this strike, Junaid Hussain, another British citizen and prominent ISIL recruiter and propagandist, was also killed in a drone strike—this one launched by the United States—outside of Raqqa.

The targeting of the British operatives could represent a significant escalation in the air campaign against ISIL. The decision to undertake the strikes in Syria, an action that Parliament explicitly prohibited when it voted to undertake military action in Iraq, has proved to be controversial. In the wake of Prime Minister Cameron’s announcement, two Green Party parliamentarians backed by the London-based human rights group Reprieve have challenged the legality of the targeted killing. Jeremy Corbyn, the new leader of the Labour Party, has also disputed the legality of the strikes. David Davis, a Conservative Party MP and former shadow home secretary, told the Guardian that while he believes that Cameron had the authority to initiate the strikes, “What I am concerned about is the possibility that this translates or becomes routinised into something like the Americans’ position.”

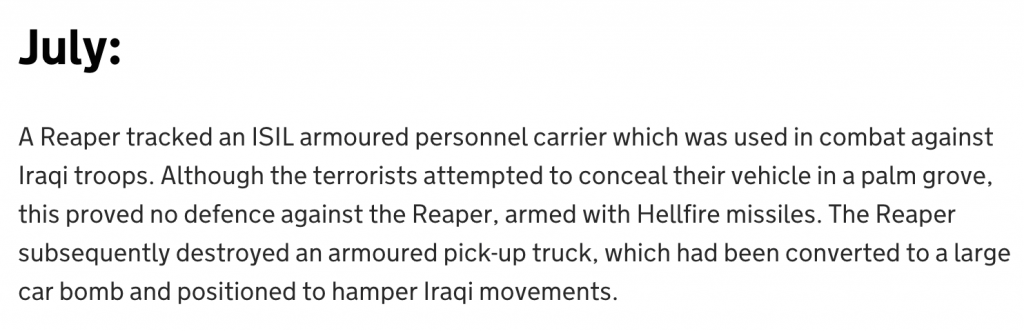

Parliament authorized the use of force in support of the Iraqi government on September 26, 2014. In the year since, the British Ministry of Defence has published short summaries of actions undertaken by its air forces as part of Operation Shader. Although these narratives cannot be considered a comprehensive accounting of Britain’s role in the campaign—they do not, for example, include the very first strikes that the RAF launched—the accounts do provide a window on how the airstrikes are being conducted, against what type of targets, and the kinds of ordnance that are used. The summaries demonstrate how drones are not just an accessory to airstrikes carried out by manned aircraft, but are in fact integral to Britain’s war effort against ISIL.

On November 10, 2014, over a month after the RAF commenced operations against ISIL, an RAF MQ-9 Reaper carried out its first strike, hitting a group of ISIL militants who were planting improvised explosive devices near Bayji, Iraq. Since then, according to the action summaries published by the Ministry of Defence, British airstrikes have been carried out almost entirely by MQ-9 Reapers and Tornado GR4s, a manned fighter aircraft. Both unmanned and manned aircraft have been engaged in an equal number of engagements, each running 137 engagements between October 5, 2014 and September 16, 2015. These strikes typically fall into three different mission types: close air support for the Iraqi Army, close air support for Kurdish forces, and patrols. They commonly target ISIL vehicles and fighting positions, as well as infrastructure like bunkers and checkpoints.

It’s difficult to draw concrete conclusions from the narratives provided by the Ministry of Defence. The consistency of the reporting varies widely in terms of the kinds of information that each account contains. We considered distinct “engagements” to be strikes separated more by time and space rather than by target type or missiles released. As such, an engagement may encompass strikes against multiple targets within the same time space and geographic area.

There are, however, a few notable takeaways that we can glean from these narratives. Of the engagements in which the mission type was reported, British MQ-9 Reapers were far more likely to provide close air support to Iraqi Army troops—59 engagements—in central and western Iraq than to Kurdish forces—16 engagements—in northern Iraq. Tornado GR4s provided more support to Kurdish forces—46 engagements—than to Iraqi troops—39. This disparity could be due in part to the location of the aircraft and the distance each has to fly to reach the target areas. According to the narratives, Tornado GR4s are based out RAF Akrotiri, an airbase in Cyprus, and are often accompanied by a Voyager refueling tanker during their mission. While it is not known exactly where the Reapers are located, it is likely that the RAF drone fleet has been based out of Ali Al Salem airbase in Kuwait. According to Chris Biggers at War is Boring, satellite imagery from January showing multiple Reapers at Ali Al Salem suggests that the drones could indeed belong to the RAF.

The MQ-9 Reapers and Tornado GR4s typically employ three types of ordnance during these missions. According to the narratives, the Reaper is equipped almost exclusively with Lockheed Martin AGM-114 Hellfire missiles, an American-made anti-tank precision missile that is used by the RAF drones that is particularly suited for use against moving targets like armed pickup trucks or even, on September 8, 2015, a boat laden with explosives. The narratives also include at least 20 instances in which Reapers were used to locate targets and track targets for other coalition manned aircraft or for ground forces. However, due to the fact that drones are frequently described as providing “overwatch”—aerial surveillance and reconnaissance—capabilities to ground forces, the number of times that enemy targets are identified for these forces is likely underreported in the narratives. The primary munition of the Tornado GR4 is the Paveway IV, a 500 lb. precision bomb. The Paveway is used extensively against a variety of targets, and in April, Defense News reported that the MoD was looking to replenish stocks of the Paveway for the anti-ISIL campaign.

The Tornado is also equipped with the MBDA Brimstone, an advanced missile that, like the Hellfire, was designed to be used against armored vehicles. Unlike the Hellfire, which has to be guided by an operator along the path of a laser to its destination, the Brimstone is known as a “fire-and-forget munition;” once released, it locks onto targets that fit pre-programmed specifications and guides itself. Both the U.K. and the U.S. have considered replacing the Hellfire missiles on the MQ-9 Reaper with Brimstones. During the 2011 Libyan air campaign, RAF forces used the Brimstone to such an extent that there were worries that British stocks of the missile would be depleted before the conflict was over. In 2013, the U.K. announced that it had finalized a $21 million deal with MBDA to replenish its stocks of Brimstone missiles. According to the MoD narratives, Brimstones were deployed repeatedly in airstrikes by Tornados against ISIL during the first six months of Britain’s participation. Beginning in April, however, the share of Tornado engagements in which a Brimstone is reported to have been released drops off precipitously, falling from over 50 percent in March to 20 percent the following month. It is possible that, as the U.K. extends its involvement in the campaign for another year, the MoD is rationing its use of the Brimstone.

In spite of gradual increase in the number of engagements involving British aircraft, the Royal Air Force are a small presence in the broader coalition against ISIL, which is led by the United States and includes Australia, Jordan, and Denmark among others. The United States also publishes summaries of actions that coalition aircraft carry out each day on the Facebook page of Operation Inherent Resolve (the American name for the anti-ISIL fight). These summaries include details on the location and target of the strike but do not define which types of aircraft are involved, or provide any more details about the missions such as whether they were conducted in support of friendly ground forces. Several journalists and NGOs are also involved in translating the information released by these governments and counting the strikes. AirWars.org, an investigative team led by Chris Woods, tracks coalition strikes and civilian casualties in Iraq and Syria. Similarly, at Drone Wars UK, Chris Cole has dug deeper into Britain’s reported of drone strikes in Iraq, providing tallies of targets destroyed.

The MoD narratives underscore the fact that the primary focus of reported RAF actions have been in support of either Iraqi or Kurdish friendly forces on the ground. This activity is in keeping with the initial goals of the bombing campaign established by the Parliament’s motion to permit military action on September 26, 2014 which recognized the “clear threat ISIL poses to the territorial integrity of Iraq and the request from the Government of Iraq for military support.” It is also in line with the initial aims of other coalition members, namely the United States. When President Obama announced on August 7, 2014 that the U.S. was beginning airstrikes in Iraq, the dangers posed by advancing ISIL forces to the Iraqi government, Kurdish cities, and minorities like the Yazidis were the rationale for military action. Unlike the American targeted killing campaigns carried out using drones by the CIA and Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) against the leaders of al-Qaeda, the contours of the air campaign have largely been shaped by the need to prevent further ISIL gains in Iraq.

Recent events suggest that the strategic emphasis of the airstrikes could shift from supporting friendly ground forces in Iraq to Syria, where the coalition appears to be taking aim at the areas in which ISIL support is strongest. “We have opportunities now [in Syria] that we didn’t think we would have. We have an opportunity to push down on Raqqa,” an anonymous U.S. official, speaking of the self-declared ISIL capital in Syria, said in an interview with the Washington Post. This shift could include a more overt push to target key leaders and operatives considered to be “high-value targets.” The first hint that this transition was underway occurred in May when it became known that American special forces had launched a raid into Syria and killed an ISIL leader known as Abu Sayyaf. American lawmakers praised the action; speaking on ABC’s This Week on May 17, Sen. Dianne Feinstein said that the raid “is the kind of one-two punch that we should do more of.” A few months later, after an August 24 drone strike killed Junaid Hussain, the Washington Post reported the CIA and JSOC were deeply engaged in targeting high-level ISIL officials and operatives, the goal being to reduce ISIL’s ability to recruit and carry out attacks outside of Iraq and Syria.

Recent events suggest that the strategic emphasis of the airstrikes could shift from supporting friendly ground forces in Iraq to Syria, where the coalition appears to be taking aim at the areas in which ISIL support is strongest. “We have opportunities now [in Syria] that we didn’t think we would have. We have an opportunity to push down on Raqqa,” an anonymous U.S. official, speaking of the self-declared ISIL capital in Syria, said in an interview with the Washington Post. This shift could include a more overt push to target key leaders and operatives considered to be “high-value targets.” The first hint that this transition was underway occurred in May when it became known that American special forces had launched a raid into Syria and killed an ISIL leader known as Abu Sayyaf. American lawmakers praised the action; speaking on ABC’s This Week on May 17, Sen. Dianne Feinstein said that the raid “is the kind of one-two punch that we should do more of.” A few months later, after an August 24 drone strike killed Junaid Hussain, the Washington Post reported the CIA and JSOC were deeply engaged in targeting high-level ISIL officials and operatives, the goal being to reduce ISIL’s ability to recruit and carry out attacks outside of Iraq and Syria.

In spite of indications that high-value targeting—also known as decapitation strikes—is assuming greater prominence within the campaign to degrade ISIL, its effectiveness as a strategy has long been disputed. In an article at War on the Rocks, Benjamin Runkle writes that decapitation strikes alone are unlikely to prove strategically conclusive unless they are paired with gains on the ground that deny ISIL sanctuaries from which to conduct operations. Recently, debates over the value of high-value targeting have been implicated in allegations that intelligence reports have been altered to a convey a more positive assessment of the progress of the air campaign. On September 20, the Daily Beast reported that, contrary to public statements by U.S. Central Command, American military intelligence analysts have voiced doubts that the deaths of ISIL leaders directly contribute to the demise of the group.

When it comes to high-value targeting, domestic security pressures in Europe and the United States may override strategic planning. The strikes that killed Reyaad Khan and Junaid Hussain were motivated at least in part by the perception among some intelligence agencies that individuals who encourage attacks against targets in the west—particularly in Europe—present a serious threat to domestic security. “[Terrorists are] using secure apps and internet communication to try to broadcast their message and incite and direct terrorism amongst people who live here who are prepared to listen to their message,” Andrew Parker, director general of MI5, said in a recent interview with the BBC. Reyaad Khan and Junaid Hussain both served as propagandists and recruiters for ISIL, and Hussain was implicated in an alleged plot to detonate a bomb at the Armed Forces Day Parade in London. Khan and Hussain are among a cadre of ISIL operatives and leaders that have been targeted in recent months and, if the targeted killing campaigns against al-Qaeda are any indication, they are unlikely to be the last.

[gview file=”http://dronecenter.bard.edu/files/2015/09/RAF-Airstrikes-Iraq-2015-Sheet11-1.pdf”]

For updates, news, and commentary, follow us on Twitter.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]