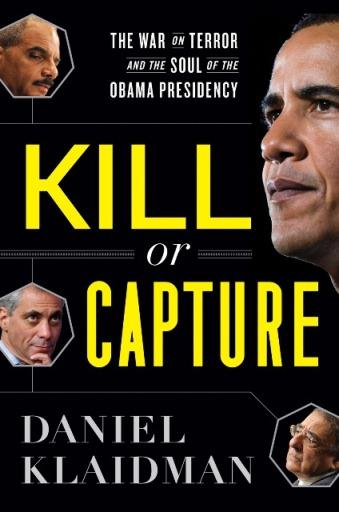

Daniel Klaidman is the author of Kill or Capture: The War on Terror and the Soul of the Obama Presidency, which has become a seminal text on the inner workings of the Obama administration’s covert drone war. Klaidman is an investigative correspondent for The Daily Beast/Newsweek, writing about the intersection of national security and Washington politics. He was the managing editor at Newsweek magazine from 2006 to 2011. As the Washington bureau chief in 2001, Mr. Klaidman led the magazine’s award-winning coverage of the September 11 attacks. He has also served as Newsweek’s Middle East correspondent in Jerusalem. On a recent visit to Bard College, Klaidman sat down with to discuss the nuts and bolts of the U.S. drone war.

Interview by Jared Rankin

Center for the Study of the Drone How did you get into this topic?

Daniel Klaidman I’m the son of a news man. My father was a reporter for The Washington Post and the New York Times and the Herald Tribune, and so I kind of fell into journalism. I spent the first part of my career working for a newspaper in Washington that covered the intersection between law, politics and policy. This ultimately led me to cover the Justice Department, law enforcement and some counterterrorism, and I eventually moved to Newsweek. I was posted overseas in the Middle East, and I started to hear about Al Qaeda. This was around the time of some of the early attacks, for example in Kenya and Tanzania. In Kenya, I spent a lot of time interviewing Arab Afghans from the fight in Afghanistan. Then I moved back to Washington to be the bureau chief at Newsweek. About two months after I got back, 9/11 happened. I could see the smoke billowing up from the Pentagon from my office window. For the next few years, that was really the focus of our Washington coverage. I started covering the Bush administration’s response to 9/11. We looked at the controversial anti-terror policies during that period: enhanced interrogation and Guantanamo. I didn’t begin to focus on drones until Obama was elected. By then I was the managing editor of Newsweek in New York. I wrote a cover story about Eric Holder, the attorney general, and the tensions within the administration over Obama’s counterterrorism policies. That cover story led to a book deal, and that led to Kill or Capture. And over time, I realized that drones and targeted killing would have to be a significant piece of the story. That’s how we got to where we are today.

Drone Even though it’s a work of investigative journalism, Kill or Capture is written almost like a novel. Can you tell me about the research and writing process?

Klaidman The researching and writing process was painful. I’ll start by saying that. It was my first book. It’s not a novel, but it is narrative. I wrote it as a narrative because that’s what I do, that’s what I grew up doing. My basic view is that this is journalism in book form. I wanted as many people as possible to read it, and I wanted to tell a compelling story that not only examines the policies but that would give readers a sense of what it was really like inside the administration as these very difficult wrenching decisions were being made.

Drone What was your relationships with the ‘cast of characters’?

Klaidman I knew some of them before I started. For example, I had known Eric Holder for many, many years. We went all the way back to when I was a cub reporter covering the local court house in Washington. My first day on the job was Holder’s first day as a superior court judge. I think we actually met that first day. But I did not know most of the characters in the book. I met some of them in the course of writing the book. Others, I never met because they refused to talk to me. I can’t name them all because some of them talked to me confidentially.

Drone Do you think “kill or capture?” is still a question that’s central to the American presidency?

Klaidman Oh, absolutely. I mean, I think it continues to be central. One of the reasons that I wanted to do the book is that there’s all this internal debate about the policy, and about whether it’s legal, whether it’s smart policy and whether it’s humanitarian. When I started the project I had no idea who was involved in the debates. I didn’t know about the president’s singular involvement in making these decisions. I remember the moment that I said to one of my sources, “Wait a second, you’re saying that the president signs off on these individual strikes?” And he said, “Absolutely.” You have to think that when the president decided to take on that responsibility it had a real political risk attached to it, because if he’s making those decisions himself, he owns them. Since I wrote the book, the strike program has diminished in terms of the number of strikes. But you still see a president who, I think, has been struggling with these decisions. I think the president deals with them on, if not on a daily basis, then almost a daily basis.

it’s smart policy and whether it’s humanitarian. When I started the project I had no idea who was involved in the debates. I didn’t know about the president’s singular involvement in making these decisions. I remember the moment that I said to one of my sources, “Wait a second, you’re saying that the president signs off on these individual strikes?” And he said, “Absolutely.” You have to think that when the president decided to take on that responsibility it had a real political risk attached to it, because if he’s making those decisions himself, he owns them. Since I wrote the book, the strike program has diminished in terms of the number of strikes. But you still see a president who, I think, has been struggling with these decisions. I think the president deals with them on, if not on a daily basis, then almost a daily basis.

They’ve been capturing more people recently, and that was something they were very hesitant to do. For political reasons and for policy reasons. They didn’t know what to do with them. There was the whole controversy over civilian trials versus military commissions, So that very central question—“Do we kill or do we capture?”—is still very front and center in this administration.

Drone Why do you think there’s been the shift from kill to capture recently?

Klaidman There was a case in 2011 Where they captured a Somali member of the Shabab named Ahmed Warsame, who was a liaison between the Shabab in Somalia and AQAP in Yemen. He was going back and forth between Yemen and Somalia and he was on the high seas. They couldn’t capture him—at least according to their policy in Yemen. They were not going to put boots on the ground because of the potential diplomatic fallout and because of force protection issues. It was the same for Somalia. But because of this individual’s role as a liaison between the two organizations, they knew he was going back and forth, and a capture on the high seas was considered much easier to execute. But there was still an enormous amount of debate before the capture. They couldn’t send him to Guantanamo because our policy is to not add any new prisoners to Guantanamo. What about bringing him to the United States? Well, the whole Khalid Shaikh Mohammed issue had exploded, and there was downright fear about how Congress would react if they immediately brought him to the United States.

Ultimately, there was an opportunity to capture him and they did, and they decided that they would put him on a ship at sea and, as one of my sources said, “make it up as we go along.” He was there for close to 80 days I think. During that time, the administration had 12 deputies or principals meetings. Those are the highest level meetings national security meetings in the White House. The fascinating thing was that they were planning the Osama Bin Laden raid at the same time. They had way more meetings about Warsame and what to do with him than they had about Osama Bin Laden. Ultimately, there was a consensus that he should be brought to the United States, and on the fourth of July 2011, he was flown to New York City. Amazingly, there was not a lot of criticism, and it faded pretty quickly. And so since then they’ve acted with more conviction and more confidence, and they’ve captured more targets. I think that’s a success story for this administration. But I think there’s truth to the idea that before that there was some kind of perverse incentive that was created, because they were unwilling to capture people and therefore they would kill them.

Drone There’s an argument that is used as a criticism of the technology of drones, the actual weapons platform, that it lowers the threshold for the kill decision.

Klaidman Yeah.

Drone Do you give credence to that argument?

Klaidman The argument that I hear mostly is that it’s as if you’re anesthetized to the killing process—that it dulls your moral sensibilities. And because there’s also no risk physical risk to you, it becomes easier to kill. And that makes killing more likely and more seductive. I think that danger is real. I can’t empirically tell you that more people were killed because of this but, intuitively, it makes sense. There’s a famous quote, which I think the CIA semi denies, book that the head of the counter-terrorism boasted that “We are killing these sons of bitches faster than they can grow them now.” There’s almost a sense of a whiff of intoxication with the ability to take out bad guys. I think that’s something that bears close watching and I think that people who are in leadership positions have to be aware of that of that risk.

it becomes easier to kill. And that makes killing more likely and more seductive. I think that danger is real. I can’t empirically tell you that more people were killed because of this but, intuitively, it makes sense. There’s a famous quote, which I think the CIA semi denies, book that the head of the counter-terrorism boasted that “We are killing these sons of bitches faster than they can grow them now.” There’s almost a sense of a whiff of intoxication with the ability to take out bad guys. I think that’s something that bears close watching and I think that people who are in leadership positions have to be aware of that of that risk.

Drone Do you think that the regular use of drones is more like policing than war?

Klaidman If you look at the sheer numbers of “suspected terrorist” or “militants”—or whatever language we want to use—who are being taken out, it belies what you sometimes hear from administration officials that they are just going after people who represent demonstrable threats to the United States. A lot of the targets were low level; if not foot soldiers, close to being foot soldiers. But I don’t think they did this because they were drunk with power. I think it’s because they believed as a matter of strategy that part of the value of the program was not just taking out individual bad guys, but rather keeping Al Qaeda disrupted: keeping them from being able to plan, and to train, and to raise money, and to have new people coming in. In the case of signature strikes, the targets were not all people who represented a real threat to the United States because in many instances the administration didn’t know who they were. Right? That’s part of the definition in a signature strike; they don’t know identities of the targets. In that sense, I think that it’s a fair criticism.

Drone Does public and international opinion factor into targeting decisions?

Klaidman I have to think that that’s factoring into their decisions and that has also factored into the President’s decision to implement these new policies.  I don’t think it’s entirely a response to pressure from the public and human rights organizations, but I think that is a part of it. Presidents are sensitive to public opinion. And they should be. I tend to doubt that there would have been as much introspection with the administration as I think there has been, if it hadn’t been for public opinion. That’s the way it ought to work. That’s the reason that organizations like yours are important, because fortunately we live in a society where civil society, civil rights organizations, civil liberties organizations, academic institutions and the press can play a role.

I don’t think it’s entirely a response to pressure from the public and human rights organizations, but I think that is a part of it. Presidents are sensitive to public opinion. And they should be. I tend to doubt that there would have been as much introspection with the administration as I think there has been, if it hadn’t been for public opinion. That’s the way it ought to work. That’s the reason that organizations like yours are important, because fortunately we live in a society where civil society, civil rights organizations, civil liberties organizations, academic institutions and the press can play a role.

Drone And yet if they are so careful, how do you targeting mistakes that result in civilian deaths happen?

Klaidman At the end of the day, you’re only as good as your intelligence is. Mistakes get made. A woman, a civilian or a child enters into the picture at the last possible second. But you’re raising a really important question, which is the accountability question. One question that has not been answered, particularly with the C.I.A program, is how many civilians have been killed. \Clearly, civilians are being killed—nobody really knows how many—but what kind of accountability is there inside the C.I.A? Has anyone ever been sanctioned? Are there any instances of people being demoted or reprimanded in some way for violating the laws of war? Does the C.I.A even feel it’s bound by the laws of war? I’ve talked to people at the C.I.A. who will not answer whether they are bound by international law when they operate. The next area of important reporting to be done is to understand what kind of accountability measures they actually have at the C.I.A.

Drone Both Jeh Johnson and Harold Koh, who were legal advisers during the early year’s of Obama’s targeted killing program, said that the targeted killing program felt like a train that was going out of control.

Klaidman It was extraordinary. They used exactly the same metaphor. And as far as I know, they did not talk to each other about that, and they found themselves on opposite sides of decisions about killing individuals. There was one member of the Shabab who Jeh thought they should go after, and Harold Koh thought that they shouldn’t. They wrote rival memos and ultimately, in that particular case, he was not killed because Harold Koh said that if they kill this person it will be over the unambiguous objection of the State Department Legal Adviser.

Drone Can you tell me a little more about the baseball cards that they used?

Klaidman The baseball cards were essentially PowerPoint slides, and the reason that the military called them baseball cards was because they had a color picture of the target, and then they had all sorts of vital stats—what team he was on, how many attacks he was responsible for, where he was in the organization, what the intelligence was based on to determine all these things. So when the military thought they had an opportunity to take out someone who was on the kill list, they had a narrow window of time, and yet they had to get a all the different agencies on board to authorize the strike. So they would send out these classified baseball cards. Harold Koh and Jeh Johnson would get them maybe 40 minutes before a strike. They described cramming before these strikes, just like you cram for an exam. Except that the stakes were higher than they are for an exam. There was something kind of macabre about it. The military has a callous sense of humor about death sometimes. I guess you have to when you’re involved in it.

and then they had all sorts of vital stats—what team he was on, how many attacks he was responsible for, where he was in the organization, what the intelligence was based on to determine all these things. So when the military thought they had an opportunity to take out someone who was on the kill list, they had a narrow window of time, and yet they had to get a all the different agencies on board to authorize the strike. So they would send out these classified baseball cards. Harold Koh and Jeh Johnson would get them maybe 40 minutes before a strike. They described cramming before these strikes, just like you cram for an exam. Except that the stakes were higher than they are for an exam. There was something kind of macabre about it. The military has a callous sense of humor about death sometimes. I guess you have to when you’re involved in it.

Drone What direction do you see Obama taking in the fight against terrorism as he carries out the rest of his term?

Klaidman The big challenge that they face is the continual splintering of Al Qaeda and all of its affiliates that are popping up in North Africa and West Africa. Obviously, you already have the affiliates in Yemen and Somalia. The emergence of all of these different groups continues to raise questions about the scope of the war and the administration’s legal authority for pursuing Al Qaeda. Most of these organizations still don’t have either the capability, or the desire, it seems, to strike against the United States or to strike out globally. They tend to be focused on provincial or at most regional issues. The administration has to watch that very, very carefully. I think Syria is a huge challenge because of the numbers of Jihadis who are moving to that front. The threats are not just to the homeland. The administration is worried about attacks against U.S. interests in the region: business interests, kidnappings of American diplomats. Benghazi was obviously a warning of that kind of threat.

But at the same time, the President wants to take the country off of a war footing. How do you balance those imperatives? I think that’s the central challenge that Obama faces going forward. I think it’s going to happen very slowly, and I think with a great deal of trepidation. The withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan by the end of 2014 should mean that that program is going to largely end in that region. If they have an opportunity to take out a very high value target—Zawahiri for example—I think they’ll probably do that, but there are legal questions once our forces are withdrawn from Afghanistan. Do we even have the authority to continue strikes in the Afghan theater after the withdrawal? The administration considers Pakistan an extension of the Afghan theater, so, except under a self defense rationale in national law, we probably won’t even have the authority to carry out drone strikes there either.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]

You may be interested in the United States planned growth for drones sponsored by DOD. Here’s the link:

http://www.defense.gov/pubs/DOD-USRM-2013.pdf