Kathryn Brimblecombe-Fox is an Australian painter whose work explores moral and ethical questions regarding the use of drones for military operations. Working under the massive Western Queensland skies, her paintings reflect an anxiety over the future and meaning of surveillance and attack drones. Her work often depicts the unmistakable stark contours of unmanned aircraft against an atmospheric backdrop that integrates mystical imagery drawn from Australia’s rich Aboriginal aesthetic tradition, offering a colorful and thought-provoking new perspective on the ongoing international debate around the use of this technology.

Interview by Maggie Barnett

Center for the Study of the Drone How did drones become a point of interest for your artwork?

Kathryn Brimblecombe-Fox Part of my current research involves an investigation of contemporary militarised technology. As a result of researching militarised drones and night vision technology, the figure of the drone has entered my paintings.

The airborne drone symbolises the present era of accelerating developments in militarised technology. It occupies imaginations in ways that infiltrate the future. In my paintings, I often juxtapose this new symbol of technology with the eons-old transcultural/religious tree-of-life symbol to trigger questions about the future of life, humanity, and the planet.

My interest in technology stems from my childhood. Although a grain farmer, my father from the age of 12 was a keen HAM radio enthusiast. I grew up surrounded by electronics: tall aerials with various antennae attached to them, communication devices in every vehicle including trucks and tractors, and world news delivered to us before it reached mainstream media outlets. As computer technology developed, my father surrounded himself with various new devices, teaching himself to fix, augment and operate them. In a pre-Internet time, on a Western Queensland farm, my father’s technological connection to the world brought it much closer.

Drone What message are you trying to convey with Dronescape? What aspect of drones are you looking to explore?

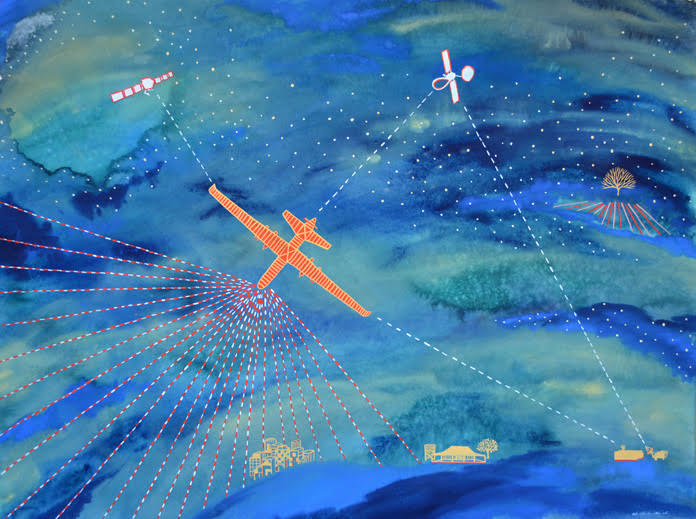

Brimblecombe-Fox I am dismayed to read reports that people, who live in places where drone surveillance and potential attack are persistent threats, are afraid of the sky—often too fearful to venture outside. I wonder about what kind of world we are living in, where on the one hand cosmological research delves into the vastness of the universe, but on the other hand some people are afraid to look up at the sky. Many of my paintings play with ideas of a ‘new sky’ created by the increasing persistence of long range and long dwell drone capabilities. I imagine skies replete with signals, data and digital images. For example, in New Sky I have painted three blue drones, each armed with Hellfire and guided bombs. Two of the drones are painted in a way that appears pixelated, mimicking a digital image. Radiating yellow lines in a micro-landscape within the larger one could be a sun’s rays, but they could also be the surveillance signals of an obscured drone. The former draws upon the cosmos, and the latter does not. This oscillation of perspectives, coupled with the upright and upside-down trees-of-life, plays with the viewer’s orientation.

Drone What does the dynamic between traditional Australian motifs and the drone symbolize?

Brimblecombe-Fox The overwhelming Australian motifs in my paintings are the landscape and distance. I grew up in Western Queensland on my parents’ grain farm. The property was in the middle of a treeless, black-soil plain. Looking west, the flat horizon sank into hazy mirages. Looking east, the majestic Bunya Mountain Range cut a dramatic silhouette. The vastness of the sky was relentless. It was most often a sheet of blue. On dark nights the Milky Way glistened as if jewels had been flung across black velvet.

I would say that my experience with distance drives my inspiration. Perhaps this is why I can ‘fly’ around the figure of the drone in my paintings, examining it from both close and far distances. Also, the colours I use come from my experience with the Australian landscape. In my paintings, the figure of the drone does seem to appropriate these colours. To speak of life giving blood and mortality, I juxtapose red drones with red trees-of-life that mimic vascular systems and other life forces, and the predominance of blue reflects the endless skies of my childhood.

Drone Much of your work features a straight or dotted line connected to a drone and often continuing beyond the spectrum of the canvas (Sky-Drone-Net, Not a Game); what physical connections are being made, and what does this mean for a world under drones?

Brimblecombe-Fox The straight or dotted lines are my attempts to make visible the unseen surveillance and targeting signals of a drone. I gain a contrary enjoyment in the knowledge that my paintings do not need the cyber or digital technology used by contemporary surveillance systems to exist. In paintings like Sky-Drone-Net and Not a Game, the dotted or straight lines extend beyond the paintings’ borders to demonstrate the ubiquity of surveillance of all kinds. The signals return to being invisible beyond the painting, but because the painting has revealed their existence the viewer’s critical reflection and imagination can take over. Here, the painting acts as a covert kind of alternative ‘surveillance’ that exposes the seemingly invisible.

French philosopher Grégoire Chamayou’s observation in A Theory of the Drone that the whole world is a potential ‘manhunting ground’ triggers an array of different images in my head. With this in mind, my emanating drone surveillance signals take on a gravitas that needs no explanation.

Drone What is your response to the increased autonomy of drones, artistically or intellectually?

Brimblecombe-Fox I question the way the drone is anthropomorphised. For example, terms like ‘drone vision’ and ‘eye in the sky’ give the drone human-like qualities, albeit seemingly enhanced ones. An ensuing fetishization of the drone, military and domestic, places humanity in a precarious position because it seduces us to view artificial intelligence and autonomous systems as proxy human beings with senses, desires, wants and rights. How does this influence decisions about meaningful human control of autonomous systems? The idea of a proxy human being already exists in the suggestion that a correlation of collected data can identify a target, named or not. The conditions for accepting increasingly autonomous drone systems exist in our human tendencies to anthropomorphise non-human and non-living entities. Also, the fast-paced nature of AI development, whilst exciting, makes it more difficult to engage in quiet and considered contemplation and critical reflection about its use in drone system autonomy.

The full Dronescapes series is available online here.

For updates, news, and commentary, follow us on Twitter.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]