By Arthur Holland Michel

Daphne du Maurier’s short story The Birds, which is about enormous flocks of birds attacking the human population of the British Isles, reveals to us a fear that we most likely won’t have to endure at any point in our lives. And yet, the story, which inspired Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 film of the same name, starring Tippi Hedren and Rod Taylor, is terrifying. One day, during a winter shortly after the Second World War, the wind turns, and a cold, dry easterly begins to buffet the English coast. Nat, a farmhand who lives in Cornwall, watches as a farmer on a tractor plows his field, a great flock of birds circling over his head, “restless, uneasy, spending themselves in motion.” “There are more birds about than usual,” the farmer later tells Nat, “I thought they’d knock my cap off!” By this point in the story, barely two pages in, you already know that something horrifying is going to happen.

The scariest parts in The Birds are not the scenes when jackdaws and gulls and sparrows swoop down on the poor people of Cornwall. Rather, what most horrifies the reader is the waiting that happens between the attacks—the sense that something inevitable, and terrible, is coming. Much of the story takes place inside Nat’s house, as he and his family hide from the flocks of birds, which relentlessly peck and scratch at the windows and doors to try and get into the house. Soon, Nat’s two young children develop a conditioned response to the sound of the birds: they cry. “Stop it,” says Johnny, the youngest child, as they hide in the kitchen. “Stop it you old birds.”

The bird’s are rarely seen at very close range by anyone except for Nat. Instead, in the daytime, the birds are seen far off in the distance, perched in trees, and on the fields, standing still and watching. As night approaches, the birds return to the houses and the cities to attack the people. Their power to terrorize and disorient is magnified by the darkness. At night, the characters feel all the more defenseless.

I first read the story when I was very young, and I remember being thoroughly spooked. I read it again recently and I couldn’t help but think of the birds as drones; the people of Cornwall as the people of Yemen; the sound of flapping wings as the buzz of a distant propeller. It almost felt like du Maurier is peering into the future when she writes that the birds have “this instinct to destroy mankind with all the deft precision of machines.” The fear experienced by the characters seemed to be the closest I have ever come to comprehending the fear that people must live with everyday in areas patrolled by, and bombarded by drones. In his statement for the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings on “Drone Wars” this past April, the 22-year-old Yemeni Farea al-Muslimi described a conversation with a boy called Ma’mon, who cried when he explained that he hears U.S. drones every night, and that every day they are afraid that the drones will come back. It is remarkable how closely the child’s reaction to the drones in Yemen resembles that of Nat’s children in The Birds. Their fear of drones and birds is rooted in their discomfort with an atmosphere dominated by the unseen presence of danger. For the young boy who speaks with al-Muslimi, the drones are all the more frightening because they are heard without being seen. Life for the boy is spent in constant anticipation of the worst. The sound of the drones is a constant reminder that the worst could happen at any moment. For most of The Birds, the children also experience the presence of the birds through their sound. The birds flap, peck, scratch, rattle and flutter against the windows and doors of the house. Their sound, like the sound of the drone, is relentless. For civilians living under drones, its sound is its most prominent and unsettling feature. According to Kathy Gannon in an article for the Associated Press, villagers in the Nangarhar province of Afghanistan have taken to calling drones “benghai,” which “in the Pashto language means the ‘buzzing of flies.'”

The Birds is a successful horror story because the subject matter lends itself to the conventions of the genre without stretching the reader’s conception of what is possible. Though the premise is fantastical, the story doesn’t feel like fantasy. As a result, the characters are sympathetic: as we watch their struggles, we experience some part of their fear. As Gina Wisker puts it in Horror Fiction: An Introduction, “The doomed, puny, human attempts to ward off the birds leave readers feeling helpless.”

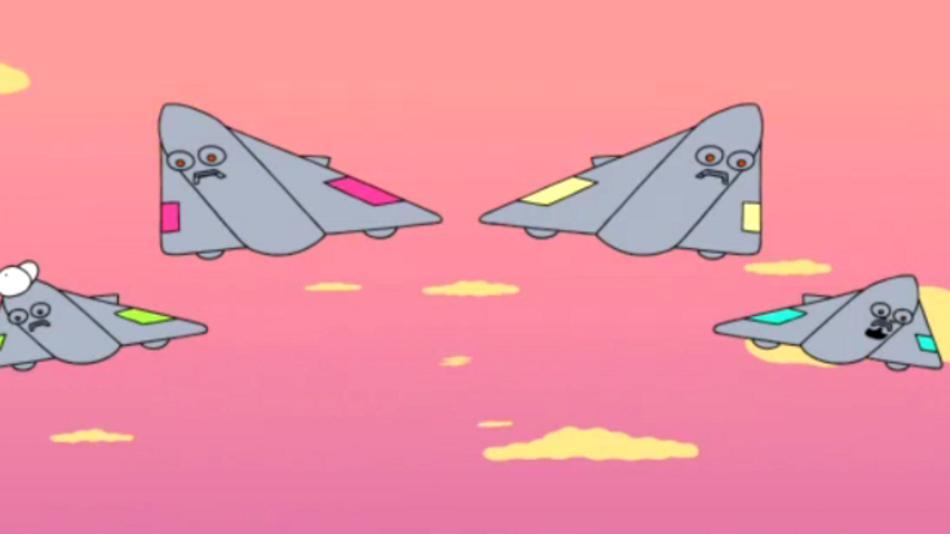

Likewise, drones seem to lend themselves particularly well to the genre of horror. It’s still a little difficult, for me at least, to get my head around the idea that there is no pilot inside the Predator. As a child, I always thought of the windows of an airplane cockpit as the eyes. Looking at a Predator, with its bulbous, eyeless face, still leaves me with the sense of looking at something deeply unfamiliar. There is a horror-movie quality to all drones, even those that are used for non-military purposes; something uncanny that seems to defy articulation. Perhaps it’s that we know, on the one hand, that the drone is entirely mechanical, and yet we can’t fully let go of the idea that there is something non-mechanical inside of it. As the famous film critic and horror expert Brigid cherry put it, our terror often lies in the tension between what is familiar and what is unfamiliar. The drone captures that tension.

In The Birds, the animals appear to have gained some new intelligence. When Nat realizes that the creatures have grown more intelligent and, as a result, more dangerous, his reaction switches from concern to terror. In their vast numbers, the birds have reasoning powers. Each individual bird is singular, expendable, and unintelligent. But as a swarm, the birds are dynamic, intelligent, and strategic. At one point, Nat attempts to read their intentions: “they know what they have to do,” he says to himself. Meanwhile, we have developed a tendency to anthropomorphize drones, even though there is something very non-human about them. We like to toy with the idea that the drone, unlike an F-16 fighter jet, or a helicopter, has feelings, and desires, and plans, and that one day, we will say of the drone, “it knows what it needs to do.” Perhaps this is not precisely the view of those who live under drones, and yet these populations surely have a sense that the drones flying over-head are working towards some strange, incomprehensible goal. When al-Muslimi spoke with other Yemenis who had been the victims of drone strikes, they asked him questions that, as he put it, “I could not answer.” He goes on, “why was the United States terrifying them with these drones? Why was the United States trying to kill a person with a missile when everyone knows where he is and he could have been easily arrested?”

Nat’s children also have questions: “Where are they flying to?” asks Nat’s daughter. “Where are they going?” The more intelligent the birds become, the more questions the characters have about them. Ostensibly, the birds are just hungry, but they also seem to have been seized by a more complex, sinister ambition. And yet, as with the people who called al-Muslimi with their questions on the night of an attack on his hometown, the answers are unavailable. The birds, like the drones, are secret, and distant. Like the birds, drones have a certain invisibility, and yet at the same time, an unrelenting presence.

The public debate about drones in America is held back, I think, by the fact that nobody really has any sense of what it is like to live under drones. If our human rights concerns about drones are based on the psychological impact of drone warfare—as was the case in Living Under Drones, which remains the most comprehensive report on the civilian impact of drone warfare—we need to develop a tangible sense of the fear that drones cause; a fear that affects everyone, indiscriminate of whether they are a civilian or not. It is, at best, coincidental that so much about The Birds seems to be describing drone warfare, and yet, if we read The Birds as a story about drones, it might well serve as an important text for people hoping to advocate against the use of drones for war, or, indeed, for domestic surveillance. At one point, early in the story, Nat is frustrated when people who haven’t themselves been attacked by birds refuse to believe how scary it is. It reminded him of the attitudes of people who hadn’t endured aerial bombardment during the Second World War. “You had to endure something yourself,” he says, “before it touched you.”