By Dan Gettinger

Operating Predator and Reaper drones over the battlefield involves dozens of people. One of the most difficult and crucial jobs within this network is that of the Joint Tactical Air Controller, or JTAC. These personnel serve as the link between troops on the ground and air assets, and are responsible for calling in air support. JTACs benefit enormously from the suite of sensors onboard the drone which can help identify possible threats nearby. They must manage highly complex airspaces that could involve multiple aircraft of varying capabilities and roles providing support.

With most of its drones tied up in overseas missions, however, the Air Force has found it difficult to find extra MQ-1 Predators or MQ-9 Reapers to train new JTACs and other ground personnel. For years, each of the military services have shelled out hundreds of thousands of dollars for contractor-operated drone surrogates, manned aircraft that simulate the function of a drone. Massachusetts-based Avwatch Inc., for example, received a $427,326 contract in 2013 to provide surrogate drone services to the Marines’ Mountain Exercise 6-13.

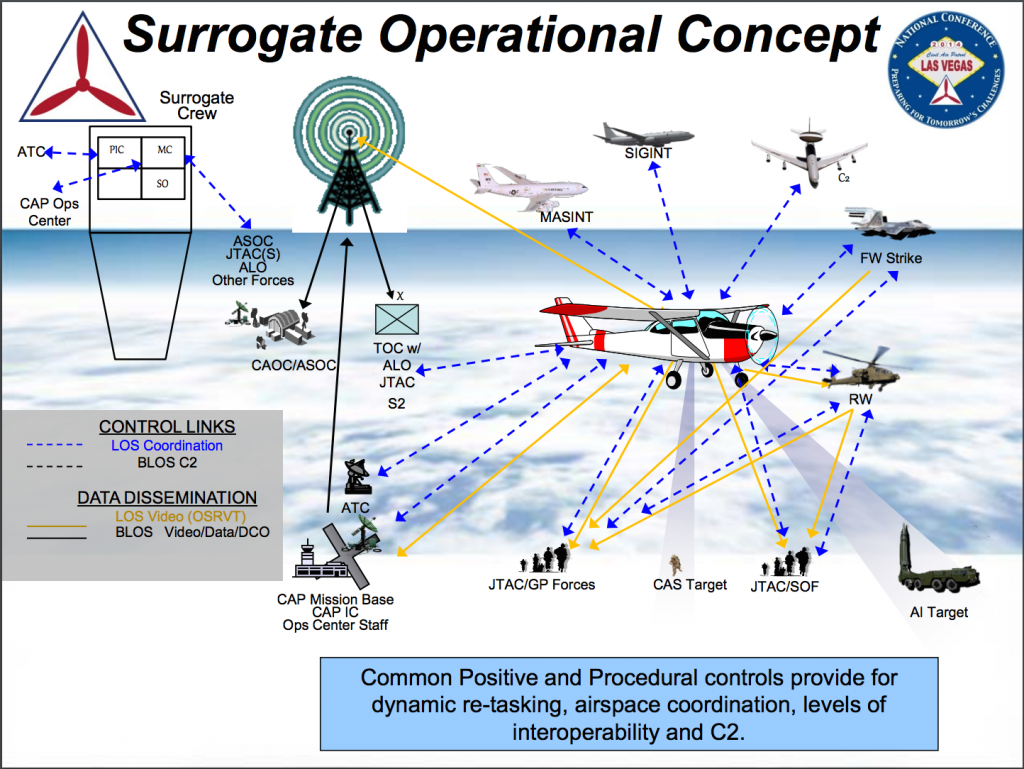

In a push to cut back on spending for drone surrogates, the Air Force turned to the Civil Air Patrol, a civilian Air Force auxiliary that trains volunteers and conducts search-and-rescue missions within the U.S. In 2009, the Air Force created the Surrogate Predator program to provide the same surveillance services during training exercises that a Predator drone might provide to ground forces in combat. The Air Force outfitted two Civil Air Patrol Cessna 182 airplanes with Wescam MX-15 camera balls, which are similar to the sensors found on its Predator drones. The idea is that these faux-drones will give JTACS-in-training a feel for what it’s like to work with a real Predator or Reaper video feed before deploying to the field. According to the FBO solicitation, the cameras were “for the purpose of pre-deployment training to simulate realistic photographic feeds like that provided by the Predator aircraft.”

The Civil Air Patrol Cessnas provide intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance services to Green Flag, a large scale training exercise involving thousands of ground personnel that emphasizes joint air-ground operations. The Cessnas are based at North Las Vegas, Nevada and Alexandria, Louisiana and are crewed by Civil Air Patrol volunteers. Each exercise lasts around 10 days and the CAP aircraft could support as many as two dozen events each year.

“It’s there to train the JTACs and to simulate having a Predator overhead so what they see and what they hear is as if a real one was there,” Chuck Mullin, the manager of special capabilities at the Civil Air Patrol, said in an interview with the Center for the Study of the Drone. “The picture they see is the same one.”

An early champion of the benefits of using CAP aircraft was Lt. Col. Matt Martin (RET), author of Predator: the Remote Control War over Iraq and Afghanistan. According to a CAP press release from 2009, Martin helped secure $2.5 million from the Air Force to fund the Surrogate Predator program. In spite of the up-front equipment costs, according to minutes from the 2010 CAP Board of Governors meeting, the operating costs of the program are lower than the contractor-operated surrogate services.

There have been two occasions when the Surrogate Predators have deviated from their regular training roles and were used for actual operations. In March 2011, the Nevada-based CAP Cessna 182 joined in the search for a private pilot who went missing after crashing in Grand Canyon National Park. Meanwhile, in 2012, the Louisiana-based CAP Surrogate Predator briefly contributed to rescue efforts following Hurricane Sandy, according to Chuck Mullin. The possibility of alternate tasking for the Cessnas, explained Mullin, has been restricted due to the CAP’s dependence on volunteers and by limits on how military assets may be used domestically.

Other government departments besides the Air Force have turned to surrogate unmanned aircraft to fill training or testing gaps. In 1996, the Navy contracted General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, the manufacturer of the Predator and Reaper, to modify a Cessna 337 Skymaster to replicate the functions of a drone. In 2012, NASA partnered with the University of North Dakota and MITRE Corporation to test sense-and-avoid systems in a Cirrus SR-22 sport plane that was outfitted to mimic a drone.

In April 2015, the Air Force Research Laboratory supplied CAP with a third modified Cessna and, according to Chuck Mullin, CAP trained another 10 new sensor operators for the program in December. “Civil Air Patrol tries to average 200 hours on our airplanes per year and the Surrogate Predator airplanes average around 500 hours per year,” Mullin said. With demand for drones outpacing the supply of aircraft, the Surrogate Predator program is likely to be around for at least a few more years.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]