By Dan Gettinger

Earlier this year, despite increasing demand for U.S. drones over Iraq and Syria, the Air Force decided to cut the number of drone missions it flies every day. The move is in response to growing concerns within the military and without that Air Force drone missions are understaffed, and that drone operators are overworked. “[W]e recognized that the path we were on was going to take us to much less capability. Until we can get enough people in the community to sustain those numbers, we’re not healthy,” Colonel James Cluff, the commander of the 432nd Wing and the 432nd Expeditionary Wing at Creech Air Force base, told Defense One this month. In response to what Secretary of the Air Force Gen. Mark Welsh III earlier this year called a “crisis” in mission fulfillment, the Air Force has made a number of personnel changes over the past few months. Some of these reforms focus on how drone pilots and sensor operators are recruited, trained, and retained. Here’s what you need to know.

Combat Air Patrols

The Air Force organizes its MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper missions in what are known as Combat Air Patrols, or orbits. Each CAP is supposed to be staffed with enough equipment (aircraft, ground control stations, satellite communications) and personnel (drone pilots, sensor operators, maintenance crews, mission coordinators, intelligence analysts, and others) to provide 24-hour coverage for a particular geographic area. A CAP typically includes four drones and around 200 personnel. In December 2009, when the Air Force had 39 CAPS, then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates set a goal of 65 drone CAPs by mid-2014, and on May 28th, 2014, the Air Force launched its 65th Combat Air Patrol. The decision by the Air Force in April will reduce the number of CAPs from 65 to 60.

Personnel

Training

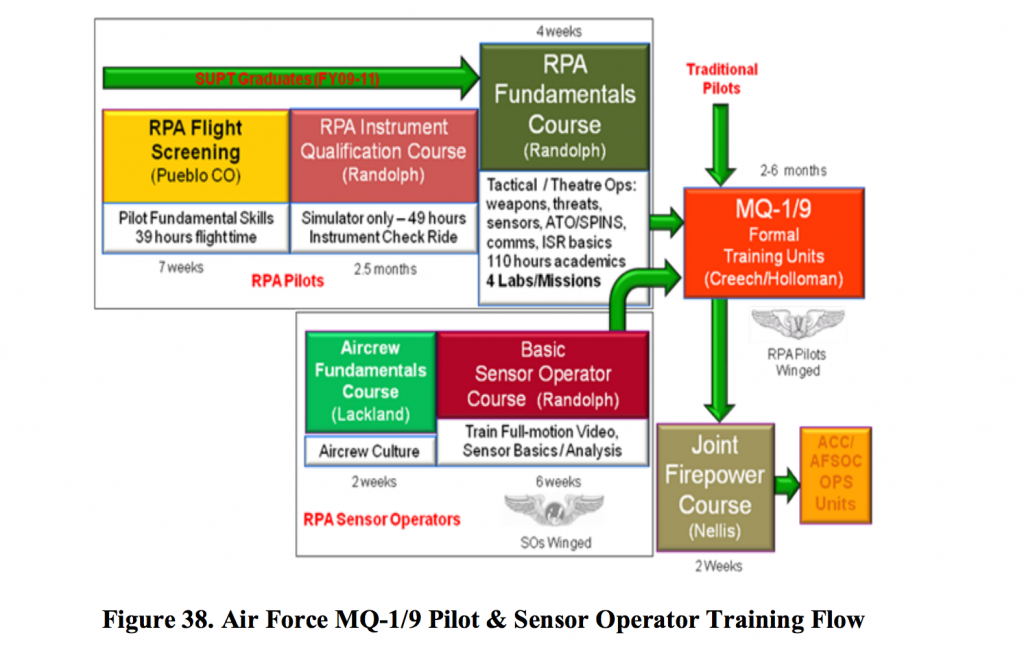

In 2009 and 2010, the Air Force overhauled the way that drone crews were trained.

- On October 23, 2009, the Air Force activated three new squadrons—the 6th Reconnaissance Squadron, 16th Training Squadron, and 29th Attack Squadron—to train new pilots and sensor operators, turning Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico into the center for training recruits. A fourth training unit, the 9th Attack Squadron, was activated in October 2012 and trains pilots specifically on the MQ-9 Reaper.

- In March 2010, the Los Angeles Times reported that the Air Force was rethinking the training of sensor operators. The overhauled program would emphasize that new recruits should behave more as co-pilots and less as imagery analysts.

- Many drone pilots trained to fly manned aircraft before being assigned to fly drones and, for many drone pilots, the assignment was temporary. For new recruits who choose the drone career field, the Air Force introduced a drone-specific training program in June 2010. The Undergraduate Remotely Piloted Aircraft Pilot Training (URT) program was part of an effort to institutionalize and formalize the unmanned aircraft career field.

- Within the Air Force, training for drone pilots is divided into two parts. During the first phase, recruits spend around five months learning to fly a manned trainer airplane, working the flight simulator, and understanding the fundamentals of flying in classroom lectures. This phase is split between Pueblo, Colorado and Randolph Air Force base in Texas. During the second phase, recruits spend three to four months in formal training, where they learn to fly a specific unmanned platform. Formal training for the MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper takes place at Holloman and training for the RQ-4 Global Hawk occurs at Beale Air Force Base in California. Sensor operators spend six weeks in an undergraduate course before joining pilots for formal training at Holloman.

Manpower Shortfalls

Even with these new training programs, the demand for drones has outpaced the Air Force’s ability to recruit, train, and retain crews.

- In a 2011 speech at the Air Force Association’s Air Warfare Symposium and Technology Exposition, Gen. William Fraser III, then air combat command commander, explained that the high demand for drones was harming the Air Force’s ability to train new pilots. “[T]raining is harder when we are putting everything forward as fast as we can. And, even with new sensors and platforms coming on at a good rate, we cannot operate on a continued surge pace indefinitely,” said Gen. Fraser. (Via “Manning the Next Unmanned Air Force”)

- In the Fiscal Year 2013 National Defense Authorization Act, Congress demanded a report from the Secretary of the Air Force on the status of training programs and promotion rates for drone crews.

- In August 2013, the Brookings Institution released a report by Colonel Bradley T. Hoagland that identified critical gaps in the Air Force’s ability to recruit and retain drone pilots. Hoagland reported that in 2012, the Air Force could fill only 82% of the open training slots for drone pilots. He also found that the promotion rate of a drone pilot was 13% lower than that of manned aircraft pilots.

- An April 2014 report by the Government Accountability Office found a multitude of deficiencies in the Air Force’s administration of the drone pilot career field. These included an inadequate crew-to-aircraft ratio, no strategy for recruiting and retaining drone pilots to meet the Air Force’s needs, and a lack of opportunity for drone pilots to conduct additional professional training and education.

- On January 4, 2015, the Daily Beast reported that the Air Force drone crews were facing critical shortfalls in manpower that were harming their ability to complete missions. “Long-term effects of this continued OPSTEMPO are manifested in declining retention among MQ-1/9 pilots, [Formal Training Unit] manning at less than 50%, and enterprise-wide pilot manning hovering at about 84%,” Air Combat Command Commander Gen. Herbert “Hawk” Carlisle wrote in an internal memo to Secretary of the Air Force Gen. Mark Welsh III.

- On January 16, 2015, the Air Force raised the incentive pay for drone crews from $650 to $1,500 as a way to attract and retain greater numbers of drone pilots. Gen. Welsh explained in a press conference that “we can only train about 180 people a year and we need 300 a year trained.” Moreover, continued Gen. Welsh, around 240 pilots were leaving the program each year and the Air Force was only able staff the training program with 63% of its required instructors. “[W]e can’t release the people from the operational units who are flying the operational support to go be training instructors, and even the people in the training units, who are there, about half of them daily are flying operational support missions,” Walsh said.

- A May 2015 report by the Government Accountability Office found that Army and Air Force drone pilots often were not able to complete their required training due to demanding operational schedules. “Pilots in all of the seven focus groups GAO conducted with Air Force UAS pilots stated that they could not conduct training in units because their units had shortages of UAS pilots,” reported the GAO to Congressional committees.

- In both the House and the Senate versions of the FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act, a total of between $56 and $76 million was allocated to the Air Force and Army drone pilot training programs. The final version of the NDAA bill has not yet been passed. “The committee is concerned that the remotely piloted aircraft career field is under severe strain because of increased combatant commander requirements, consistently insufficient Air Force personnel policy actions to improve manning levels, and is compounded by the Air Force losing more remotely piloted aircraft pilots than it is training.” – Senate Armed Services Committee report on the FY16 National Defense Authorization Act

Psychological Effects

A number of the aforementioned reports identify psychological stresses and low morale as potential explanations as to why the Air Force has such trouble retaining its crews. “Lack of adequate or appropriate recognition is a factor for lower promotion rates,” writes Col. Hoagland. “One of the controversies surrounding their historical lack of high level recognition is the viewpoint that RPA pilots were not risking their lives while operating their aircraft 7,000 miles away in Nevada.” The April 2014 GAO report found that the Air Force needed to address difficult work environment elements such as long hours. It also found that the Air Force had not fully analyzed some of the challenges faced by drone crews in adapting to dual roles of deployment and civilian life: “RPA pilots in each of the 10 focus groups we conducted reported that being deployed-on-station negatively affected their quality of life, as it was challenging for them to balance their warfighting responsibilities with their personal lives for extended periods of time.” In addition to these reports, investigations by military psychologists and journalists have supported claims that drone crews face a number of psychological pressures, for which the high demand for their services might be partially responsible.

- In a 2008 report titled “A Resurvey of Shift Work-Related Fatigue in MQ-1 Predator Unmanned Aircraft System Crewmembers,” researchers at the Naval Postgraduate School found that drone pilots and sensor operators were more likely to show signs of severe fatigue than crews of any other “high-demand/low-density” platform. The report suggested that chronic fatigue among drone crews could be one reason why the crews were understaffed.

- A June 2011 report by the School of Aerospace Medicine found that RPA crews remained at risk to “occupational burnout” and were at greater levels of “high operational stress” in comparison to Air Force service members in support or logistics jobs. Among the 1,500 airmen surveyed, many cited the long hours (50+ among active duty), sustaining day and night operations, and the daily transition from military to civilian lifestyles—known as “combat compartmentalization”—as the main sources of stress.

- A 2013 report by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center compared RPA crews to those of manned aircraft. The authors found that drone crews are at equal risk of mental illnesses as the crews of manned aircraft, suggesting that the “social isolation” that accompanies flying drones could increase susceptibility to disorders.

- In a letter to Secretary of the Air Force General Mark Welsh III on June 25, 2015, Senator Claire McCaskill (D-MO) expressed concern that drone crews were overburdened, writing that there could be unknown psychological effects of flying unmanned aircraft.

For updates, news, and commentary, follow us on Twitter.

[includeme file=”tools/sympa/drones_sub.php”]